On Saturday, I went to the last performance of Don Carlo, and what will be my last performance of the Met season. It was an evening both grand and thrilling, with a musical and dramatic force that reminded me forcibly of what opera's capabilities are. The performance of the Met orchestra under Yannick Nézet-Séguin was nothing less than world-class, and was supremely exciting. They played with drive and nuance throughout, and from the beginning, Verdi's motifs were highlighted and treated with great dignity. Individual and section highlights, too, were all gorgeously handled, honoring both the forward momentum of the score, and its suspense. The singing, too, was excellent; my companion repeatedly asked who the casting director was, which drew my attention to my ignorance of this process. But those responsible certainly deserve praise. This was indeed a cast not only universally strong, but with good chemistry, and some choreography new to this iteration of Nicholas Hytner's 2009 production. More than once during the evening, I found myself thinking that the Met would do well to have more such productions in its rotation: visually striking, thoughtful in interpretation, and with a strong dramatic arc that still leaves room for adaptation to individual singers.

On Saturday, I went to the last performance of Don Carlo, and what will be my last performance of the Met season. It was an evening both grand and thrilling, with a musical and dramatic force that reminded me forcibly of what opera's capabilities are. The performance of the Met orchestra under Yannick Nézet-Séguin was nothing less than world-class, and was supremely exciting. They played with drive and nuance throughout, and from the beginning, Verdi's motifs were highlighted and treated with great dignity. Individual and section highlights, too, were all gorgeously handled, honoring both the forward momentum of the score, and its suspense. The singing, too, was excellent; my companion repeatedly asked who the casting director was, which drew my attention to my ignorance of this process. But those responsible certainly deserve praise. This was indeed a cast not only universally strong, but with good chemistry, and some choreography new to this iteration of Nicholas Hytner's 2009 production. More than once during the evening, I found myself thinking that the Met would do well to have more such productions in its rotation: visually striking, thoughtful in interpretation, and with a strong dramatic arc that still leaves room for adaptation to individual singers.In the evening's cast there was not a weak link. Robert Pomakov was suitably impressive as the friar whose commentary on the vanity of worldly power sets the tone for the claustrophobic drama that is to follow. James Morris, while with a less stentorian sound than is usual for the Grand Inquisitor, was (I thought) splendid in the role, with unusually elegant phrasing, good use of text, and of course, huge amounts of gravitas. Nadia Krasteva, making her Met debut in the role, was an exciting and dynamic Eboli. Unusually (in my experience of Ebolis,) Krasteva made the ferocity and sensuality of the character both credible, and she handled phrasing well. The integration of her registers was not always perfectly smooth, but pristine accuracy is not what I most want from Eboli. To have a compellingly passionate, intelligent one was a treat. Commentary on Ferruccio Furlanetto's Filippo would seem almost superfluous, but last night's performance proved that he is not resting on his laurels. His presence is absolutely compelling, his use of text chillingly effective. More even than this, he gave a performance of great immediacy, as well as of great authority; every decision of the king seemed to be weighed in the moment, every emotion keenly and freshly felt. The emotional and dramatic pacing of Ella giammai m'amò was extraordinary. It is, of course, an iconic aria; Furlanetto gave it its full, shocking intimacy, with the use of its silences, as well as incredible richness of textual coloring, to show us the dangerous vulnerability of a tyrant. And his treatment of the queen's jewelry box--gazing at it, caressing it, whether absently or with dreadful fixity--set up the following scene brilliantly. Furlanetto's Filippo was also brilliant in interactions (both public and private) with the rest of the court. I could gush further; happily, the audience (along with the orchestra, conductor, and cast) acknowledged what we were hearing, with riotous and prolonged acclaim.

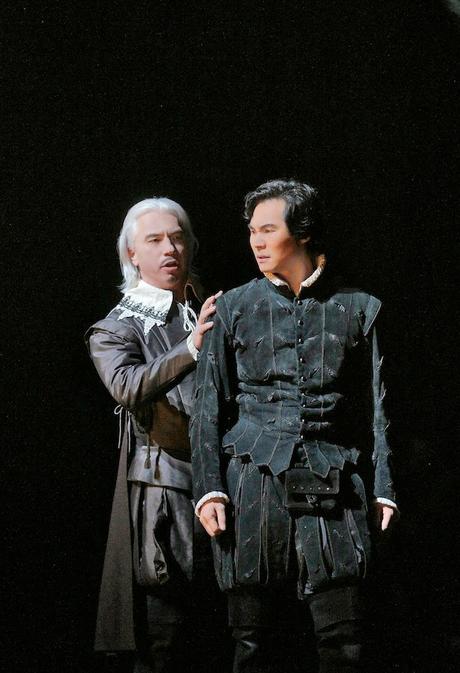

The other principals, while perhaps--and not inappropriately--in the king's shadow, gave strong and nuanced performances. It was a treat to hear Dmitri Hvorostovsky, an experienced exponent of the role, as Rodrigo, of whom I am always fond. The role sits well for Hvorostovksy, and he was in fine form, providing elegant and rich-toned singing, and suitable emotional intensity in both his private and political missions. He also gave great weight to Rodrigo's powerful one-liners, begging the queen to read letters, the king not to become a tyrant, Eboli to subscribe to his version of the truth, and Carlo... Carlo to act the prince, to take comfort, to know how much he is loved. Hvorostovsky was especially strong in the duets with Carlo and with the king, and his death scene--magnificently paced, and not at all excessively histrionic--was accompanied by a soft, stifled sobbing from multiple points in the house (including the seats where my friend and I sat.) I love the relationship between Rodrigo and Carlo at all times, and when, as here, Rodrigo is selflessly and uncomplainingly in love with his friend, it just breaks my heart. Hvorostovsky and Lee were both excellent in their handling of the telling gesture; here, when Rodrigo is shot, Carlo's first action is to rush to the impassive soldiers, to try to discover whose was the shot. Failing, he presses himself against the blank wall of the prison, as if it is only now, most bitterly, that he feels himself truly isolated, truly trapped. It is only Rodrigo's plea for his hand that rouses him, to hold in his arms his beloved friend. Also excellent was the Elisabetta of Barbara Frittoli. In the past, I've found Frittoli to be a somewhat uneven, though always interesting singer; I was delighted by her portrayal of Elisabetta. Her phrasing was elegant, her singing warm and emotionally engaged, as well as technically solid. I was also impressed by her characterization of Elisabetta as a woman of strong affections, as well as a strong sense of duty. Her relationship with Carlo was tender as well as anguished, with a very moving garden duet. Frittoli handled the remarkable demands of "Tu che le vanità" with remarkable power and expressivity, the final duet with no visible strain. As Don Carlo, Yonghoon Lee gave a sit-up-and-take-notice turn. From the opening scene, he was engaged and engaging. His singing was both stylish and passionate, and he displayed a sizable and attractive sound. I've been impressed vocally by Lee in the past, and his Don Carlo was nuanced and compelling, as well as finely sung. The tragedy of the evening is a complete one; but the audience had cause to go home exulting.

The other principals, while perhaps--and not inappropriately--in the king's shadow, gave strong and nuanced performances. It was a treat to hear Dmitri Hvorostovsky, an experienced exponent of the role, as Rodrigo, of whom I am always fond. The role sits well for Hvorostovksy, and he was in fine form, providing elegant and rich-toned singing, and suitable emotional intensity in both his private and political missions. He also gave great weight to Rodrigo's powerful one-liners, begging the queen to read letters, the king not to become a tyrant, Eboli to subscribe to his version of the truth, and Carlo... Carlo to act the prince, to take comfort, to know how much he is loved. Hvorostovsky was especially strong in the duets with Carlo and with the king, and his death scene--magnificently paced, and not at all excessively histrionic--was accompanied by a soft, stifled sobbing from multiple points in the house (including the seats where my friend and I sat.) I love the relationship between Rodrigo and Carlo at all times, and when, as here, Rodrigo is selflessly and uncomplainingly in love with his friend, it just breaks my heart. Hvorostovsky and Lee were both excellent in their handling of the telling gesture; here, when Rodrigo is shot, Carlo's first action is to rush to the impassive soldiers, to try to discover whose was the shot. Failing, he presses himself against the blank wall of the prison, as if it is only now, most bitterly, that he feels himself truly isolated, truly trapped. It is only Rodrigo's plea for his hand that rouses him, to hold in his arms his beloved friend. Also excellent was the Elisabetta of Barbara Frittoli. In the past, I've found Frittoli to be a somewhat uneven, though always interesting singer; I was delighted by her portrayal of Elisabetta. Her phrasing was elegant, her singing warm and emotionally engaged, as well as technically solid. I was also impressed by her characterization of Elisabetta as a woman of strong affections, as well as a strong sense of duty. Her relationship with Carlo was tender as well as anguished, with a very moving garden duet. Frittoli handled the remarkable demands of "Tu che le vanità" with remarkable power and expressivity, the final duet with no visible strain. As Don Carlo, Yonghoon Lee gave a sit-up-and-take-notice turn. From the opening scene, he was engaged and engaging. His singing was both stylish and passionate, and he displayed a sizable and attractive sound. I've been impressed vocally by Lee in the past, and his Don Carlo was nuanced and compelling, as well as finely sung. The tragedy of the evening is a complete one; but the audience had cause to go home exulting.