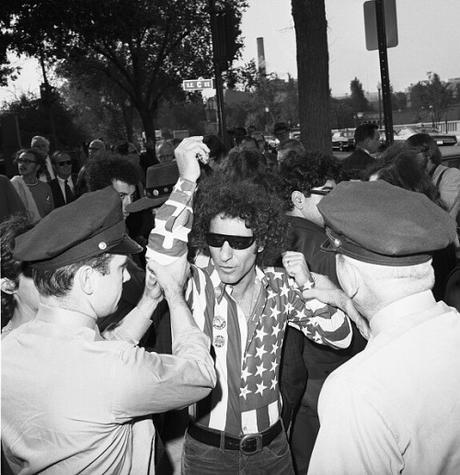

In October 1968, Abbie Hoffman showed up to the House Un-American Activities Committee while wearing shirt fashioned to look like an American flag. A leading proponent of the flower power movement, Hoffman was a radical socialist, an anarchist, and the co-founder of the Youth International Party (or “Yippies”). He was also present at the 1968 Democratic National Convention riot, where tens of thousands of protesters descended on Chicago to rally against the Vietnam War. The brutal assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. earlier that year had left the country reeling, and the strife within the Democratic Party was laid bare when Chicago saw bloodshed from protestors and bystanders alike. Consequently, the House committee asked Hoffman to come testify. But when the capitol police saw him approaching in his red, white, and blue shirt, a brawl ensued. They ripped the shirt off his back and threw him in jail.

Hoffman is the first person to be arrested for wearing the American flag — an act considered by some to be a desecration of a sacred national symbol. “I wore the shirt because I was going before the Un-American Activities Committee of the House of Representatives, and I don’t particularly consider that committee American, and I don’t consider that House of Representatives particularly representative,” Hoffman later explained. “And I wore the shirt to show that we were in the tradition of the founding fathers of this country.” Hoffman went on to win his case on an appeal. But when the first judge found him guilty, he uttered the immortal words: “I only regret that I have but one shirt to give for my country,” following American hero Nathan Hale’s famous last words in 1776 before being executed by the British for being a spy.

Oh, if Hoffman could have only lived to see today’s politics. For their annual Rolling Thunder motorcycle demonstration, the group AMVETS (American Veterans) used to ride into the US capitol on their metal steeds to gather around the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery. Most bikers don somber black t-shirts with black leather jackets decorated with Vietnam War pins. But some attendees, including the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and four-star general Richard Myers, have been seen at the wreath-laying ceremony while wearing an American flag shirt. It’s just one of the many examples of how flag-emblazoned clothing has been negotiated and re-negotiated, claimed and re-claimed, by different citizens for different purposes. Being that 2020 is an election year, flag-themed clothing is sure to crop up again as fashion companies push out their designs. The question is: are they violating the US flag code?

In popular representation, our religious reverence for the flag dates back to the American Revolution. Emanuel Leutze’s painting “Washington Crossing the Delaware” shows the nation’s most famous Founding Father leading the Continental Army with a flag whipping in the wind behind him. But according to Marc Leepson’s Flag: An American Biography, flagmania didn’t begin until the Civil War. For nearly 100 years of this nation’s history, the government mainly used flags to mark federal facilities and military outposts. It was almost unheard of for private citizens to display one at their homes, let alone on their bodies.

That all changed in April 1861 when the Confederates attacked Union outpost Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, which marked the beginning of the American Civil War. “When the stars and stripes went down at Sumter, they went up in every town and county in the loyal states,” Admiral George Preble wrote in 1871. “Every city, town, and village suddenly blossomed with banners.” The attack on Fort Sumter, Preble continued, “created great enthusiasm throughout the loyal States, for the flag had come to have a new and strange significance. The heart of the nation swelled to avenge the insult cast by traitors on its glorious flag. It is said that even laborers wept in the street for the degradation of their country. One cry was raised, drowning all other voices — ‘War! War to restore the Union! War to avenge the flag!’”

When the war came to a close, flagmania remained. To capitalize on this groundswell of patriotism, businesses started printing the banner on advertisements and product labels, including those slapped across whiskey and beer bottles. Such promotion didn’t sit well with patriots, who felt the sacred symbol shouldn’t be used for crass commercial endeavors. Towards the end of the 19th century, individual states started passing flag-protection laws, which regulated the use of flag imagery. While reverence for the flag started in the north, it spread nationwide through a subsequent series of events — the breakout of the Spanish American War, the introduction of Flag Day, the Pledge of Allegiance in schools, and the start and growth of patriotic groups such as the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution.

By 1942, shortly after the first American troops landed in Europe to fight the Nazis, the cult of the flag reached an all-time peak. The US government that year ratified its first Flag Code, which is an advisory set of rules for the care and display of the nation’s most cherished symbol. The code prohibits the use of the flag in advertising, its embroidery on things such as cushions, and its imprinting on disposable items such as paper napkins and boxes. Section 176 also frowns upon the use of Old Glory in apparel, including sports uniforms, costumes, and yes, even daily attire.

There’s one exception. The code allows for flag pins, which are considered replicas of the real thing. But since the flag represents a living country, proper use of the pin means that you can only display it on the left lapel, near your heart. This symbol first made its way into politics in the 1970s, when Republican congressional candidates started wearing them as a subtle counterpoint to protestors who were burning the flag in the streets.

The flag pin, however, didn’t become a True Patriot shibboleth until President Richard Nixon started sporting one. According to his biographer Stephen Ambrose, Nixon adopted the practice on the suggestion of his Chief of Staff, H.R. Haldeman, who had noticed a similar gesture in the Robert Redford film The Candidate. Ironically, he wore the metal bauble to deflect criticisms that he wasn’t loyal to his country or office, even if his actions told a different story. Nixon’s pin graced his lapel as he lied to the American public about his involvement in Watergate, and later when he resigned from office.

In the following decades, the pin’s popularity rose and fell according to national sentiment. During the First Gulf War, they sold briskly alongside flag patches and bright yellow ribbons. They returned with a vengeance after 9/11. Grand displays of patriotism at the time were used for many things. For most people, it was a way to bolster national unity and feel safe within their communities. But it didn’t take very long for the “rally 'round the flag” effect to get co-opted. Soon, the pin became a symbol of that silencing sentiment, “you’re either with us or against us.” It was a sign of “not just patriotism, but also an uncritical view of the government at a time when the country was marching toward what turned out to be a disastrous war in Iraq.”

Even the media got involved in the hawkish theatrics. While other news anchors debated the ethics of wearing a pin on air, those on Fox News eagerly wore the accessory. “Why would it ever be inappropriate?” asked Fox News’ commentator Brit Hume. “It doesn’t stand for the Bush administration or a certain party or even the government. It stands for the country. Why is wearing a symbol of the country of which you’re a citizen a problem?” Greg Dyke, the director-general of the BBC at the time, noted that “many US networks wrapped themselves in the American flag and swapped impartiality for patriotism.” Notably, some people were beyond reproach. “Watch me, and you’ll know what I think without [me] wearing a pin,” Bill O'Reilly said at the time. When recently asked why he wasn’t wearing an American flag pin at his confirmation hearing, General John Kelly sharply replied, “I am an American flag.”

By 2007, the Iraq War lost popular support among the American people. Given the pin’s muddled associations, some Democratic candidates toyed with the idea of discarding it entirely. During a TV interview, an Iowa ABC reporter asked Obama why he hadn’t festooned his lapel with the accessory. The then-Senator said he hoped his patriotism showed through his actions. “The truth is that right after 9/11, I had a pin,” Obama replied. “Shortly after 9/11, particularly because as we’re talking about the Iraq War, that became a substitute for I think true patriotism, which is speaking out on issues that are of importance to our national security. I decided I won’t wear that pin on my chest. Instead, I’m going to try to tell the American people what I believe will make this country great, and hopefully, that will be a testament to my patriotism.”

Naturally, that answer didn’t sit well with the portion of the public who saw pins as the most outward manifestation of what’s inside a person’s heart. Obama eventually acquiesced and wore a pin for the rest of his candidacy and presidency. But that didn’t dispell with racist myths that he was neither of this country or loyal to it. When his pin occasionally swiveled upside down — another violation of flag code — some saw it as a Carol Burnett ear-pull to his Muslim Brotherhood friends. Not more than a year later, when White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer emerged for a press briefing with an upside-down flag pin, the press joked he was only sending distress signals.

In April 1989, Abbie Hoffman committed suicide in his home on Sugan Road in Solebury Township, Pennsylvania. His body was found surrounded by some 200 pages of notes, many of which cataloged his moods. He was diagnosed with bipolar disorder earlier that decade, but some who were close to him say he took his own life for other reasons. He was reportedly depressed about reaching middle-age, his 83-year old mother had cancer, and he was dismayed that the younger generation was not interested in social activism. The liberal upheaval of the 1960s had produced a conservative backlash in the 1980s. All of his efforts seemed to have come to naught.

That summer, just a few short months after Hoffman’s death, the Supreme Court ruled flag-protection laws unconstitutional. The US flag code is still very much in the books, but it’s intended to be a guideline for best practices, not enforceable laws. Today, you can produce, sell, and wear anything with the American flag and for any reason. Madonna draped herself in an actual flag in 1990 for a “Rock the Vote” ad that aired on MTV; Juelz Santana covered himself head-to-toe in flag clothing for his “Dipset Anthem” music video; and Jessica Simpson wore a red, white, and blue bikini on the cover of GQ.

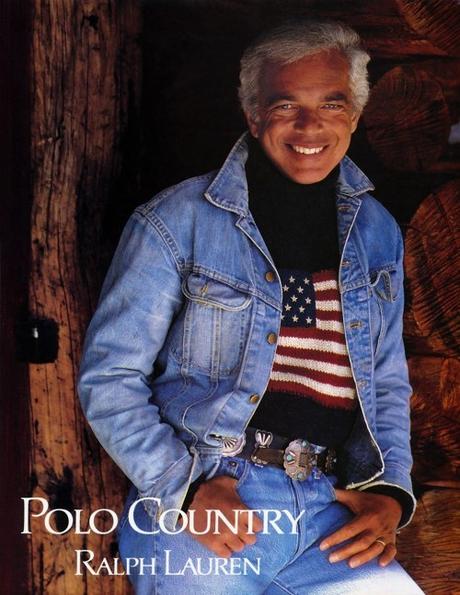

Old Glory has also cropped up on popular fashion. Fifty years after the police arrested Hoffman for wearing his flag shirt, the banner is now plastered on everything from suits to socks. Ralph Lauren and Tommy Hilfiger are particularly well-known for using the stars and stripes. Target’s first collaboration with a fashion designer showed patriotic themes in a collection named Americaland. The symbol has also become important abroad. French designer Catherine Malandrino unveiled her American flag dress in the summer of 2001, which became popular in the aftermath of 9/11. Visvim’s Hiroki Nakamura has also used the motif in shirts, shoes, and outerwear.

If you think some of those designs are questionable, consider the star-and-stripes condoms that were distributed in 1990 with the slogan “never flown at half-mast.” Or the patriotic pasties, contact lenses, and diapers that have made it to market. “It is spreading — literally — from top to bottom, from tricolored wigs to toilet seats, planes and trains to municipal fireplugs, Tiffany diadems to morticians’ coffins,” Time Magazine noted in 1976. “An instant industry has sprung up manufacturing Bicentennial gewgaws such as plastic tricornes, birthday buttons, patriotic bikinis, and tricolor towels. With pride, affection, and occasional humor, from motives ranging from crass commercialism to plain and fancy patriotism, Americans are splashing the land with primary color that, for a change, has nothing to do with elections.”

“A thoughtful mind, when it sees a nation’s flag, sees not the flag, but the nation itself. And whatever may be its symbols, its insignia, he reads chiefly in the flag, the government, the principles, the truths, the history that belongs to the nation that sets it forth. The American flag has been a symbol of Liberty, and men rejoiced in it.” -American abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher

Unlike other patriotic items — such as cups, pens, and other tschokes — flag imagery on clothing is unique. Clothing is distinctive in that it’s personal and corporal. The very bodies used to support such clothing changes the meaning of what’s being displayed. In ancient Greece, the bodies chosen to carry the flag during the Olympics were based on size, looks, and character. In this way, the spirit of the nation was best represented through the actual body of the flag’s carrier. This Olympic tradition continued in the United States up until 1968. That year, instead of the usual male body used to represent America, a female fencer named Janice Romary hoisted the US flag during the opening ceremony at the Mexico City games.

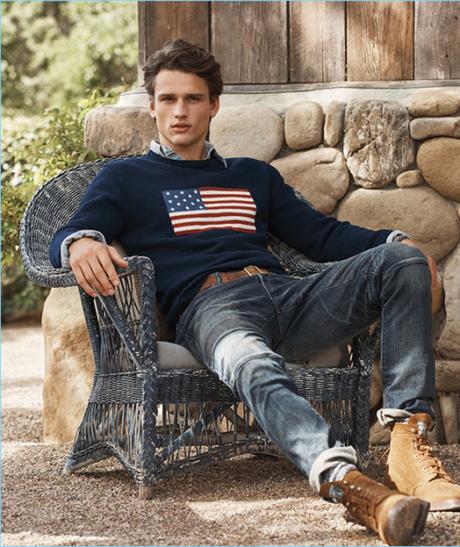

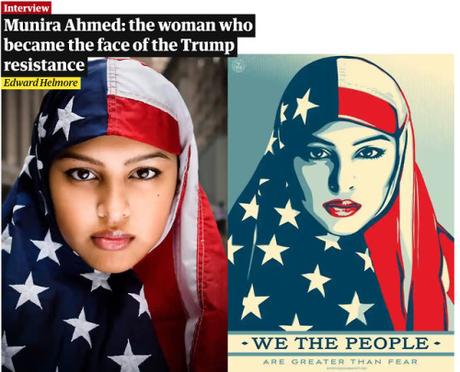

You can see this clearly in the Shepard Fairey’s rendering of Munira Ahmed above. In a poster series called “We the People,” Fairy included the image of a young Muslim woman wearing the US flag as a headscarf. If it weren’t for flag-emblazoned clothing, what other patriotic accessories can so clearly communicate the diversity that makes up the cloth of this nation? Certainly not bedding or dinnerwear. Even if in limited terms, clothing can communicate otherwise inexpressible emotions. One of my favorite pieces is Ralph Lauren’s 9/11 tribute sweater, pictured above, which memorializes the service members who lost their lives during that September day’s attack.

With a US Presidential election around the corner, flag-emblazoned clothing is already hitting stores. Takahiromiyashita The Soloist has a flag jacket; John Elliott has flag shorts; and Gosha Rubchinskiy has flag tees. Visvim is offering a pair of stars-and-stripes geta sandals this season if you want to make your way through the snow in open-toed shoes. They’re a dizzying $2,175 but shipping is free.

More relatably, I like this Chamula flag sweater. It’s a riff off of one of Ralph Lauren’s most iconic designs, which has been offered every season for as long as I can remember. Ralph Lauren’s sweater is knitted in the United States, making it more apt for such a patriotic garment. But with all that has happened in the last few years – arguments about the US southern-border wall, Brexit, the rise of ethnonationalism and nativism, and the retreat of cosmopolitanism and internationalism – I actually like that this American flag sweater was designed by a Japanese man living in America, and then handknitted by native craftspeople in Mexico.

Additionally, Brooks Brothers has flag-motif cufflinks, while RRL offers a rather well-designed flag pin. Over at Etsy, you can find things such as vintage flag brooches, belt buckles, and pins (I prefer the Olympic ones for their nod towards a friendlier version of nationalism). Dapper Classics also has Republican, Democrat, and non-denominational flag socks. Their socks are knitted in North Carolina using top-end yarns and then hand-linked at the toes. They’re exceptionally comfortable and well-made, and one of the few flag-related accessories you can wear with tailored clothing. I bought a pair earlier this year and plan to wear them to my department’s election-themed events.

One of the reasons why flag clothing today is so contested is because the symbol itself means so many different things to different people. For some, it’s a representation of the country’s best values; for others, it means imperialism, hubris, and narcissism. All of those things are true at the same time, as American society is both complex and contradictory. We want to be liberal, meaning inclusive, but also communitarian. We value equality and freedom, even if those values are, at times, opposed.

Does flag clothing violate flag code? Yes, technically, but the code itself is so muddled, it ought to be re-written anyway. Callouts on this issue often feel like a pointless game of “gotcha,” where people on both sides of the political aisle throw barbs to no end. In actual practice, flag clothing allows us to reflect the many views and backgrounds that make up American society. For me, the US flag is still the greatest symbol of those 17th-century ideas held to be true. Those ideas are in the rallying cry of the French Revolution, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.” Or the single phrase of the American Revolution with the greatest continuing importance, that all men are born equal and free.

Most importantly, flag clothing allows us to renegotiate the symbol’s meaning with our bodies and personalities, which in turn helps to redefine patriotism. This doesn’t take away from the symbol’s glory, but rather adds to it. In his Flag Day address in June 1917, barely two months after the American entry into World War I, President Woodrow Wilson expressed this sentiment beautifully:

This flag, which we honor and under which we serve, is the emblem of our unity, our power, our thought and purpose as a nation. It has no other character than that which we give it from generation to generation. The choices are ours. It floats in majestic silence above the hosts that execute those choices, whether in peace or in war. And yet, though silent, it speaks to us –- speaks to us of the past, of the men and women who went before us, and of the records they wrote upon it.