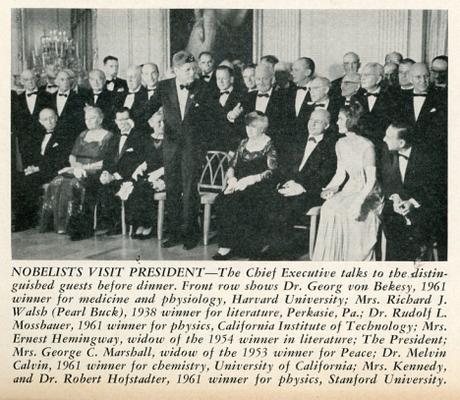

Science News Letter, May 12, 1962

[Ed Note: Today we are pleased to publish this guest post authored by Joseph A. Esposito, who served in three presidential administrations. His book on the Nobel Prize dinner will be published in 2018 by Fore Edge, an imprint of the University Press of New England.]

As the nation grapples with polarization and rancor, it is instructive to look at the state of discourse a half century ago. Perhaps there is no better prism to do so than the dinner that President and Mrs. John F. Kennedy hosted for Nobel Prize winners and other American intellectuals fifty-five years ago, on April 29, 1962.

Coming at the mid-point of the Kennedy presidency, this dinner honored forty-nine Nobel laureates and spoke to the accomplishments of America while at the height of its power during the Cold War era. In the background, foreign and domestic challenges faced the country as the rivalry with the Soviet Union was intense and growing; race relations were frayed and becoming increasingly violent; and a number of important social issues were just emerging.

But there was optimism. Certainly this dinner celebrated American achievement and a belief that the United States could tackle and surmount any problem. And surely part of that feeling was due to the leadership exhibited by the president. Kennedy, whatever his flaws, was a charismatic figure who used words to inspire while understanding the need to be conciliatory and pragmatic in dealing with public issues.

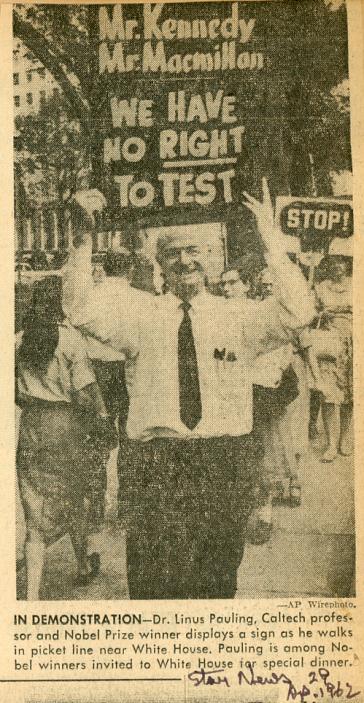

Pasadena (California) Star-News, April 29, 1962

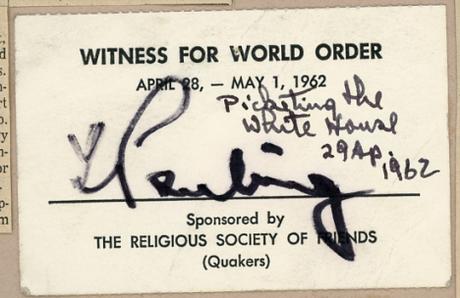

Prior to the dinner, Linus Pauling, the 1954 Nobel laureate in Chemistry, had been picketing the White House for the previous two days because of stalled nuclear test ban talks with the Soviet Union and the announcement that the United States would resume its own testing following a four-year halt. After picketing on the Sunday that the event was to be held, Pauling and his activist wife, Ava Helen, changed for dinner and headed to the White House.

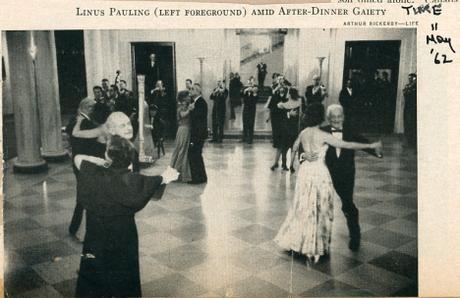

In the receiving line, Kennedy greeted Pauling cordially, commending him for expressing his views. Pauling was ambivalent about Kennedy, but enjoyed himself that evening, even leading the dancing.

As the dinner was being held, the Tony Awards were also being presented in New York. The award for drama went to the play “A Man for All Seasons,” which is about Thomas More, who placed principle over loyalty to his government; Paul Schofield was honored with a Tony for his role as the lead character. Linus Pauling might have smiled about the coincidence. Pauling subsequently received a second Nobel Prize for Peace, the culmination of years’ worth of social activism such as he had exhibited that day. A nuclear test ban agreement was signed in 1963.

Time, May 11, 1962.

James Baldwin was another guest at the White House dinner. Baldwin, then thirty-seven years old, had already written several books, including Notes of a Native Son. He would interact with Robert Kennedy at the Nobel event, and this conversation would have important implications for the civil rights movement. One year later, Baldwin and Robert Kennedy met with African American leaders in New York. The meeting was acrimonious, but it proved educational for the attorney general. Eighteen days later, President Kennedy delivered his famous civil rights speech in which he envisioned the future Civil Rights Act. As it turned out, his brother was alone among his advisors in supporting this televised address.

Also present at the White House gathering was J. Robert Oppenheimer, who had run afoul of McCarthyism and had his security clearance revoked by the Eisenhower administration. Having spent the past eight years in political purgatory, Oppenheimer was invited by Kennedy to the gala dinner. The President understood the value of reconciliation and redemption; the following year, Kennedy selected the “Father of the Atomic Bomb” for the prestigious Fermi Award.

Indeed, the dinner brought together some of the nation’s greatest minds. Among the collection of writers present were Robert Frost, Pearl Buck, John Dos Passos, William Styron, and Katherine Anne Porter, whose A Ship of Fools became the number one bestseller that day. The scientists in the room included Glenn Seaborg, responsible for the discovery of ten elements; several others associated with the Manhattan Project; and a veritable who’s who of American physicists, chemists, biologists and medical researchers. Astronaut John Glenn, the hero of the hour who had recently orbited the Earth, was also there.

Much has been made about Camelot, a focus that will surely intensify during the upcoming centennial of John F. Kennedy’s birth. And while images of the 1,036-day presidency of the young leader will forever be intertwined with his untimely, tragic death, it is also clear that Kennedy could uplift the nation through soaring words, measured action, and the ability to bring together people who sought only America’s best interests. A partisan when necessary, he also understood civility and the value of respectful dialog.

So too was Linus Pauling a man who respected principal and the exchange of ideas. While he appreciated that special evening in 1962 and had been hopeful of the young president’s potential, he was not reluctant to speak out about the great issues of the day. Above all, Linus Pauling was a distinguished scientist and a committed activist for peace. He was truly “a man for all seasons.” We can learn much from him as well.

Advertisements