While working on the rhizomatic animism post the other day, I kept thinking about the old cliche that a picture is worth a thousand words. Tim Ingold’s use of simple line drawings to depict different ways of perceiving life (or being in the world) is incredibly powerful. His diagrams also reminded me of an earlier post in which I commented on the non-progressive nature of evolution. That post prompted some spirited discussion from some of my best internet friends. I now want to follow up on that discussion with some more depictions.

Let’s start with this famous diagram, the tree of life, by German naturalist Ernst Haeckel:

When the history of life is depicted in this way, it sends the unmistakable message that evolution is progressive: it begins at the base or root with single-celled organisms and over evolutionary time it grows. At the apex or crown is magnificent man, the implied telos or outcome of all this evolution. It’s a tidy progressive portrait: simplicity at the bottom, complexity at the top.

Thanks to the genius of Carl Woese, we no longer represent the history of life in this way. Instead we depict organisms as being rooted in a primordial last common ancestor that has given rise to all existing life forms on earth today:

As I noted earlier, an anthropocentric perspective which places humans at the center of everything creates the illusion that evolution is progressive or directed toward some goal. It isn’t. Life began on earth some 3 billion years ago and after 3 billion years of evolution, the vast majority of life forms remains simple. We live in a (simple) microbial world, not a (complex) intelligent one.

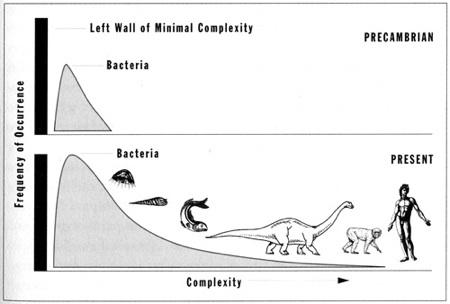

If microbes could write evolutionary history, things would look much different. In the absence of such a history the next best thing is Stephen Jay Gould’s Full House (1997), which shatters the illusion that evolution is progressive. The greatest frequency or mode of life on earth, in terms of biomass and diversity, microbial. It remains firmly against the left wall of minimal complexity, close to where it began.

My observation prompted Tom Rees to comment: “The graph does show that evolution is directional. Complex brains have to build on less complex brains.” Because I didn’t explain the graph very well, I responded to Tom by noting that directional evolution is in the eye of the human (or primate or mammal) beholder. The mode of life — its greatest frequency, biomass, and diversity — is up against (or near) the left wall of non-complexity. It started there, and after evolving for over 3 billion years, it has remained there. This doesn’t look very directional.

Toward the left side of non-complexity and non-intelligence, we have microbes and, moving toward the right, we have insects. In terms of numbers, species, biomass, and diversity, these are the dominant forms of life on earth. These forms are still evolving, but they aren’t evolving towards complexity or intelligence.

Our multicellular prejudice — our love for big things that we can easily observe — causes us to focus on the right side of complexity and intelligence, and then claim that these relatively few and non-diverse species indicate evolution is directional. I don’t see how we can justify this argument.

Isolating a single and uncommon strand of evolution, such as the right tail of complexity or intelligence, doesn’t make evolution directional to the right. The fact remains that the isolated right tail of evolution is dwarfed by the diversity and mass of life to the left, which is non-complex and non-intelligent. This mass of life to the left has not been static either; it too has evolved — it just hasn’t evolved towards complexity or intelligence.

I’m not sure what the rationale or argument would be for mono-focusing on the right tail, which is an evolutionary outlier, and not considering everything to the left. If we look at the whole or entire picture of evolutionary life, it is non-directional. If evolution were directional, then all forms of life would show movement toward the right or towards multi-cellularity, complexity, sentience, and intelligence. That hasn’t happened and isn’t happening. Microbes, insects, and fish completely dominate life on earth and none of them are moving in this direction or progressively evolving towards complexity.

This exchange prompted Alex Fairchild to chime in with this bit of brilliance:

When I try to explain this concept, I attempt to describe the tree of life as being contained within a sphere, with the center being the LCA (“last common ancestor”) of life, and the surface being the present, and each branch tip being a species. The surface of the sphere is vast, with billions of species, each just as old as the other. only by picking one (the human branch), and looking back down the tree, do you see a directionality towards intelligence. Picking a random branch will land you on a one celled organism, with near certainty.

This is a fantastic way of word-visualizing the evolutionary history of life on earth from past to present. Until recently I was not able to find any good images depicting his words. I now have two, both of which were created for other reasons. I really like this first one because we can imagine the small starting dot as the last common ancestor, and the expansion as the burgeoning history of life during the past 3 billion years — the end points are the present:

Humans, of course, are just a single strand at the very end of one of these lines. Here is a static view, with humans being just a single point at the end of a single strand:

The only deficiency in this depiction is that there are billions of living species on earth, so we need billions of lines and points at the outer fringes (or present). Our diagrams obviously can’t do this, but we can imagine it. We can also imagine humans being just one of those billion points.

The only deficiency in this depiction is that there are billions of living species on earth, so we need billions of lines and points at the outer fringes (or present). Our diagrams obviously can’t do this, but we can imagine it. We can also imagine humans being just one of those billion points.