When we look at tea, especially Chinese tea which has a long illustrious history, you can count on there are no shortage of tales associated with it.

Some of it is factual, some of it is fiction. Some of it probably begun as fact but was sensationalized over time.

Let’s look at reasons for the prevalence of fables.

Fiction is more interesting

Take the example of Shuixian or 水仙.

The Chinese language is character base and phrases often take on an entirely different meaning from the individual words.

Individually, Shui (水) is translated as water and Xian (仙) as immortal, fairy or sprite- anyway you look at it, an ethereal being.

There are some who take these words and run with it, firstly translating Shuixian as water (insert own immortal being) fairy and concocting their own fancy version of the time when immortals roam the earth.

A discerning tea lover would realize that Chinese tea vendor who target primarily ethnic Chinese and other serious tea drinkers almost always translate it as one of the following: Sacred Lily, Daffodil or Narcissus.

Properly understood, when combined Shuixian refers to the species of flower Narcissus tazetta which is also known by one of the names mentioned above.

Going one step further, the most logical explanation of how this tea came to be known by this name is that it was first discovered in Zhuxian (祝仙) cave which sounds like Shuixian in the local Minbei accent in JianOu (建瓯).

A somewhat mundane tale with very little spice but unfortunately truth is often as such.

Lack of Understanding of the Context

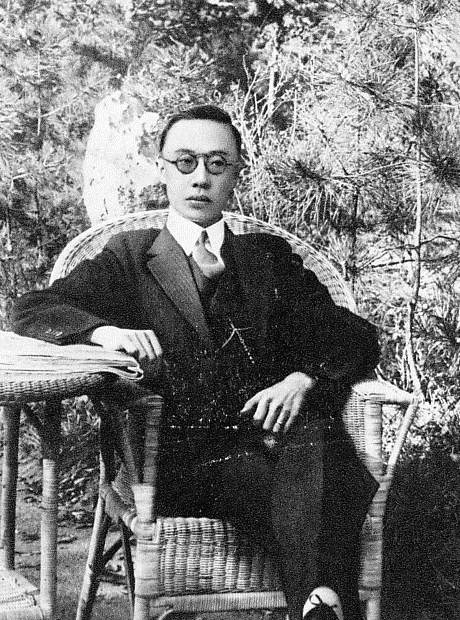

Taken from WikiCommons

Let me use the oft repeated tale of Shennong’s discovery of tea as an illustration.

The common tale goes along this line: In 2700 BCE Emperor Shennong was boiling a kettle/cauldron of water when a tea leaf floated into the kettle and transformed it into a magical tasting elixir.

I don’t know about you guys but if I add 1 leaf, even if it is the largest Yunnan Dayezhong (云南大叶种) leaf, to a tea pot of say 250 ml, it is not going to taste very different from water.

This is to say nothing of unprocessed raw leaf. Remember most tea leaves are rolled (揉捻) to ‘squeeze’ the juices out and aid dissolvability. Raw leaf is not.

A few more things to consider:

2 things were written in the ancient texts about this-

i) “茶之饮,发乎神农”

Which simply means- the consumption of tea originated from Shen Nong

‘神农尝百草以疗疾,一日遇七十二毒,得荼而解之’ - Taken from “Shen Nong’s Herbalism Manual” (神农本草)- author unknown

The text simply says: ‘Shen Nong experimented with hundreds of herbs in search of a remedy and was poisoned with 72 toxins that were cured by ‘Tu’’ (an early form of the word 茶 which is of course tea).

You can read more about that here. Nothing about floating leaf and in fact nothing about boiling water either.

In the olden days- before lab mice and stem cells- herbalists experimented on themselves. Most likely Shennong ate the leaf as part of his ‘research’.

In addition, the discovery of boiling water as a means of killing bacteria was commonly attributed to Shennong or at least his clan. Hence along the way someone kind of combined his 2 discoveries.

Origin Claims

If you understand Chinese culture, you would realize that being the originator is a big thing.

The Chinese phrase is a beautiful one: “正宗原味” or “true ancestry and original taste”.

Legends often lend credence to their claims of being the originator.

Take the example of Tieguanyin.

The 2 most famous tales are Wei’s tales (Goddess in a dream) and Wang’s tale (Emperor bestowing the name) which you can read about here.

Did you know that to this day the descendants of Wei and Wang are still disputing who the originator of Tieguanyin is? Notwithstanding 4-5 centuries having transpired.

This is how much Chinese culture values being the origin.

Memories are often fleeting but tales help reinforce them. Consequentially, outside of China most people only know ‘Wei’s tale’ because it is a more colorful one and if they ever travel to Xiping, Anxi they can still find the descendants of Wei Yin making tea.

The Wei clan have their ancestor to thank for inventing a more interesting tale.

Adding to the Perceived Value

Just like restaurant owners love displaying some ancient photographs of some celebrities in their outlet, having a famous person associated with a tea adds to the perceived value of it.

Image taken from WikiCommons

Emperor Qian Long is a perennial favorite, having traveled incognito 6 times to Jiangnan. Hence you would hear of numerous Jiangnan teas- most notably Xihu Longjing being associated with him. Not to mention the fact that Qian Long is well-known for his love of tea.

Some sites choosing not to research a bit more merely label certain teas tribute teas.

For instance, at least one site called Yunnan Black aka Dian Hong a tribute tea for royalty, notwithstanding the fact that it was created AFTER the founding of the new republic.

It would have been a nice gesture for tea to be sent to north where former emperor Puyi resided all the way from Yunnan as a tribute, especially considering that there was a Sino-Japanese war ongoing at that time.

History is Separate from Fables

However that is not to say everything we know is fiction

It just takes some knowledge and discernment to weed out the legend.

For instance the discovery of wulong tea (oolong) may have numerous legends associated with it, but there is reliable documentation that can help in establishing the truth.

Demystifying Chinese tea entails separating fact from fiction but don’t throw out the proverbial baby with the bath water. There is so much that is fascinating and informative about tea history that shouldn’t be buried by the wayside or marginalized.

See here for more articles on the history of tea

See here for part I of Demystifying Tea- How to Taste Tea