(Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis)

"Ample evidence" exists to charge the company and executives with willfully providing the public erroneous and incomplete information in construction of the Kemper Plant near De Kalb, Mississippi, according to a report at the Journal of Forensic and Investigative Accounting (JFIA).

Further, the report finds, "the blatant disregard of proper accounting techniques in composing the company financial statements led to the complicity of the auditor, (Deloitte & Touche), in perpetrating the fraud."

Ample evidence of providing erroneous and incomplete information? Blatant disregard of proper accounting techniques in perpetrating the fraud? That is devastating language directed at Southern Company, especially when it comes from an academic journal under the headline "A Saga of Clean-Coal Electric Power: The Multibillion-Dollar Southern Company Fraud."

Is this a major story in the energy and accounting industries? The introduction to the JFIA report strongly suggests the answer is yes:

Southern Company (Southern) is a publicly traded holding company (NYSE: SO) that, in part, provides electricity to several states in the Southeast, including Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi. According to Southern’s website (southerncompany.com), the company is one of the largest producers of electricity in the country and the leading provider in the Southeast region.

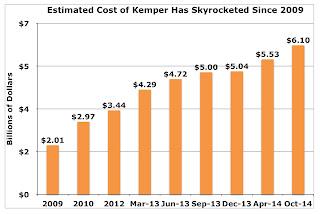

Through events dating back more than a decade, Southern became embroiled in a costly (an approximately $7 billion loss) and shockingly mismanaged coal power plant construction project in Kemper County, Mississippi.

The plant was originally planned to be located at the Orlando Utilities Commission’s Stanton Energy Center in Florida, and the Department of Energy was to provide $407 million funding. The promised clean-coal power plant drew visitors from Saudi Arabia, Japan, and Norway. Jukka Uosukainen, the U.N. Director of Climate Technology Centre and Network, said Kemper was an example of how using coal in the future is possible. Its builders claimed the project was the moonshot of the 1960s (Kelly, 2018). Southern was accused of illegal and fraudulent acts relating to the construction project, which was eventually abandoned.

Southern Company's "moonshot" wound up producing more lawsuits than energy, JFIA reports:

Several civil lawsuits were filed against the company, resulting in settlements for the plaintiffs. For example, a federal judge in the U.S. Northern District Georgia Court ruled that Southern must pay $87.5 million to investors harmed by Southern’s actions over the period of April 2012 through October 2013, wherein the company finally disclosed cost overruns and construction delays of the power plant. These disclosures ostensibly precipitated a significant drop in thecompany’s share price and devaluation of the company by approximately $1.3 billion (Lubitz, 2020). This class-action lawsuit, filed on behalf of the Monroe County Employees’ Retirement System, claims the defendant violated Sections 10(b) and 20(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, alleging materially misleading financial statements (Monroe County Employees’ Retirement System v. The Southern Company, 2021).

Although legal actions were taken against Southern itself, only recently has legal action been taken against the company’s auditors. On February 17, 2022, a class- action suit was filed against Deloitte & Touche, LLP (Deloitte) in the U.S. Northern District of Georgia, claiming that Deloitte abdicated its responsibility to ensure the accuracy of Southern Company’s publicly issued financial statements (Formby v. Deloitte & Touche, LLP, 2022). Throughout the lawsuit class period (May 2010 until February 2020), Deloitte’s audit reports stated that the financial statements were presented fairly, in all material respects. The plaintiff’s claim that Deloitte violated Rule 10b-5 of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934, wherein the defendant “recklessly violated its professional responsibilities,” thereby fostering fraud and deceit upon Southern shareholders and the public at large (Formby v. Deloitte & Touche, LLP, 2022).

How did the "moonshot" go so wildly off course. Over-exuberant politicians and scientists were part of the problem, along with poorly conceived state legislation, The JFIA reports:

One of the four public utility companies that Southern owns is Mississippi Power Company. With the price of natural gas rising due to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Southern hit upon the idea, heavily promoted by then President Barack Obama and former Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour, of producing electricity in the Kemper County plant by turning lignite coal, which is plentiful in the region, into clean synthetic gas in a process called coal gasification. Using Transport Integrated Gasification (TRIG) technology, the Kemper plant would become an integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) facility. In such a facility, the coal is not burned directly, but undergoes a reaction with oxygen to create a synthetic gas (syngas), which is then combusted in a generator to produce electricity. Theoretically, this combination process broadens fuel flexibility, is more efficient, and decreases emissions as compared to traditional coal-fire facilities. (Wang and Stiegel, 2017).

Lignite reserves mined by Liberty Fuels were near the Kemper plant site owned by Mississippi Power Company. The region, which had a low per capita income and rather high unemployment rate, would benefit from clean power and the preservation of coal-mining jobs. An estimated three million metric tons of carbon dioxide produced as a byproduct would be captured and piped to two oil fields to bring oil to levels where it could be accessed. This process is called carbon recapture. In February 2006, Southern was awarded a Cooperative Agreement by the Department of Energy to provide financial support under the Clean Coal Power Initiative (CCPI) for developing and using TRIG. Before Haley Barbour became governor of Mississippi, he was Southern’s chief lobbyist and was instrumental in transferring millions of dollars in federal subsidiaries from a cancelled Florida coal plant to the Kemper plant. Mississippi Power received authorization from the Mississippi Public Service Commission in June 2010, on the acquisition, construction, and operation of the plant.

After an Environmental Impact Statement was accepted, groundbreaking for the facility occurred in December 2010. Southern had given assurances that the project would be completed by May 2014 and cost no more than $2.88 billion. A groundbreaking ceremony occurred on December 16, 2010, with less than three and one-half years to finish the project. The Mississippi Base Load Act was passed in 2008 which allowed utility companies to charge their customers for projects that were not yet finished. Also, the Act allowed recovery of prudently incurred pre-construction costs, even if construction never commenced; permitted recovery of prudently incurred construction costs even if the plant was never completed; and permitted recovery of prudently incurred “operating and related costs,” even if the plant was never placed in commercial operation. However, this Act only “empowers and authorizes” the Public Service Commission to allow utilities to charge their customers, according to Mississippi Attorney General James Hood on April 14, 2009 (Kasper, 2016; Miss. Code Ann. Section 77-3-105(1)(b)). Tony Bartelme, a reporter for the South Carolina Post Courier, explained South Carolina’s Base Load Review Act with the analogy that it was like paying a grocer as it builds its store—with the hope that groceries might be a little cheaper when it opens (Crumbley, 2022).

Significant financial incentives might have caused Southern Company to cut corners and push schedules to the max. The company wound up sending mixed messages. From JFIA:

The following statement appeared in Southern’s 2012 10-K Report: The Company’s current cost estimate for the Kemper IGCC ... is approximately $2.88 billion ... While the Company continues to believe its cost estimate and scheduled projection remain appropriate based on the current status of the project, it is possible that the Company could experience further cost increases and/or schedule delays with respect to the Kemper IGCC (Southern Company, 2013). This statement was made after numerous news releases saying that the project was on schedule and within the cost target.

If the project were completed on time and within the budget, Kemper would qualify for nearly $700 million in federal incentives. If the project were not completed on time and within budget, ratepayers could not be charged for any costs above the projected $2.88 billion (e.g., shareholders would be held responsible for any cost overruns). Furthermore, federal incentives would be lost, a deal with South Mississippi Electric Power Association for $275 million in exchange for a 15 percent ownership interest in the Kemper plant would have to be repaid with interest, and an agreement with Treetop Midstream Services to purchase the carbon dioxide byproduct would be forfeited.

In November 2012, an Independent Project Schedule and Cost Evaluation Report stated that the Kemper plant’s schedule was already three months behind where it should be, and, therefore, the total project cost would be more than $3 billion. The project manager responded, in the Independent Monitor’s Project Schedule and Cost Evaluation, that some basic management and control techniques were not being utilized and some needed deliveries were behind schedule (Formby v. Deloitte & Touche, LLP, 2022). On November 29, a spokesperson for Southern disputed the report.

Throughout the first half of 2013, Southern reiterated its belief that the Kemper plant would be in service in May 2014. The facility had reached several major construction milestones. On April 24, 2013, Southern’s CEO, Tom Fanning, in an earnings call described “tremendous progress” on construction even though there was a $540-million budget hike. He said that the 174-feet tall coal storage building was already “in place.”

The white dome cement ceiling, however, was already crumbling because of sloppy workmanship, and by early March had a hole the size of a house (Kelly, 2018). Should the external auditors have known about the hole?

Finally, in October 2013, Southern announced that the plant would not be ready in May 2014 and, therefore, would have to repay the $133 million in federal tax credits. But the plant would still be completed in 2014, and the company would be eligible for approximately $150 million in tax credits. In Mississippi Power Company’s First Quarter 2014 Filing, Southern stated in October 2013, that it would not meet the May 2014 completion date and that the project wassignificantly over budget. In its first quarter 2014 SEC filing, the company stated the following:

On April 28, 2014, Mississippi Power further revised its cost estimate for the Kemper IGCC to approximately $4.44 billion ... The revised cost estimate primarily reflects costs related to decreases in construction labor productivity at the Kemper IGCC ... Mississippi Power currently expects to place the combined cycle and the associated common facilities portion of the Kemper IGCC project in service in the summer of 2014 and continues to focus on completing the remainder of the Kemper IGCC, including the gasification system (Southern Company, 2014).

A Southern Company insider played a central role in bringing the problems at Kemper to public attention, writes JFIA:

In 2012, a whistleblower named Brett Wingo came forward. He alleged that the Kemper project was mismanaged and that Southern fraudulently concealed cost overruns and project delays. After state regulators renewed Kemper’s license to continue with the project, Mississippi Power informed them that they had concealed cost overruns of about $366 million.

Wingo kept telling supervisors that the information being given to the public was misleading. Wingo was not the only one who had concerns. The Independent Monitor hired by the state also grew skeptical. Although engineers told management in February 2014 that the company should not promise completion of the project by the year’s end, Southern ignored that advice. The engineers were told by plant managers to present an optimistic picture to avoid a financial calamity.

Southern Company sued Wingo on February 19, 2015, to stop him from talking, based upon an unsigned agreement to terminate his employment. Judge Elisabeth French dismissed the case and lifted the restraining against him (Associated Press, 2015).

Wingo provided The New York Times with “thousands of pages of public records, previously undisclosed internal documents and emails, and 200 hours of secretly though legally recorded conversations among more than a dozen colleagues” (Urbina, 2016).

Wingo was subsequently fired when he would not keep quiet about Southern’s management. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration subsequently ruled that the firing was illegal, he should be rehired, and paid back wages and benefits. He had been offered $975,000 by the company to keep quiet but he did not stop talking. (Urbina, 2016; Amy, 2017).

Exposing the truth proved damaging to Wingo's career:

In February 2015, the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled that the Mississippi Power Company could not raise rates to customers for cost overruns on a plant prior to becoming operational, and they had to refund 186,000 ratepayers related to utility increases. Consequently, shareholders had to absorb the losses.

Wingo filed a whistleblower-retaliation lawsuit against Southern in August 2017, stating that an order to reinstate him was being ignored. He claimed he had reported safety concerns and unrealistic construction schedules internally, but he was warned that he was “digging a hole for his career and not to become a martyr.” Wingo had raised these concerns to executives as high as CEO Tom Fanning and to PricewaterhouseCoopers which was managing the project before Wingo was fired (Urbina, 2016).

The following appeared in Southern’s 2014 annual report:

Construction of the Kemper IGCC is nearing completion and start-up activities will continue until the Kemper IGCC is placed in service ... The Company ... continues to focus on completing the remainder of the Kemper IGCC, including the gasifier and the gas clean-up facilities, for which the in-service date is currently expected to occur in the first half of 2016. (Southern Company, 2015a). For the costs approved for a cap of up to $2.88 billion, the current estimate listed in the report is $4.93 billion with actual costs incurred as of the end of 2014 at $4.23 billion. The income statement shows estimated losses on Kemper IGCC to be $868 million in 2014 and $1.18 billion in 2013.

In its 2013 10-K report, Southern stated that the Kemper plant is scheduled to be in-service in the fourth quarter of 2014. In March, Brett Wingo told the chief executive officer that the project could not be completed by then and that it was fraudulent to say so or sign a financial report saying so. In its 10-Q report filed in May, Southern stated its in-service date for the completion of the Kemper IGCC to be in the first half of 2015. In a hearing before the Mississippi Public Service Commission in July, Greg Zoll, the project manager for Burns and Roe Enterprises, Inc., who was hired by the Mississippi Public Utilities staff to act as an independent monitor for the Kemper plant, testified that the company did not admit to major cost increases and delays that it knew about as early as September 2011.

On August 9, 2014, the Kemper facility was placed into commercial service using natural gas, according to the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management (FECM). With offices in Washington, D.C. and Germantown, Maryland, FECM, with 750 employees, “is responsible for Federal research, development, and demonstrated efforts on advancing technologies to meet our climate goals and minimize the environmental impacts of fossil-fuel use ...” (About Us, ND).

This statement appeared in Southern’s first quarter 2015 SEC filing: Mississippi Power’s current cost estimate for the Kemper IGCC in total is approximately $6.22 billion, which includes approximately $4.94 billion of costs subject to the construction cost cap ... The in-service date for the remainder of the Kemper IGCC [including the gasifier and the gas clean-up facilities] is currently expected to occur in the first half of 2016. (Southern Company, 2015b). In the first quarter 10-Q report, it was stated that estimated probable losses on the Kemper IGCC of $9 million for and $380 million for 2014 were recorded in the first quarters to reflect revisions of estimated costs expected to be incurred beyond the $2.88 billion cost cap. In the 2013 first quarter, $462 billion was recorded as an estimated loss on Kemper IGCC.

The in-service date for Kemper kept getting pushed back, from third quarter 2016 to March 2017. What was Deloitte doing as schedules kept shifting? The answer is not clear, but legal problems continued to mount. From JFIA:

As Deloitte has done throughout the period of time of developing the Kemper IGCC, the firm stated that the financial statements present fairly the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows in conformity with U.S. generally accepted accounting principles.

On June 9, 2016, Treetop Midstream Services sued Southern Company and Mississippi Power for terminating their contract to receive carbon dioxide on June 3, 2016. Treetop claimed that Mississippi Power lied and concealed delays in the Kemper plant construction. Treetop asserted that it was required to finish a $100-million pipeline nine months before Kemper started coal operations (Amy, 2016). The pipeline “to nowhere” was to deliver the carbon dioxide to Tellus Energy to use in drilling operations (Amy, 2016). Treetop claims that Mississippi Power knew the plant would not be ready by May 2014. (Mr. Dunn, ND)

A warning by Black & Veatch, an independent consulting firm hired by Southern, stated that the construction was too aggressive, did not include sufficient scheduling contingencies, and lacked appropriate workforce or resource loading. A November 2012 report by Burns & Roe Enterprises, Inc., an independent monitor hired by Mississippi Public Service Commission, indicated that there was “zero probability that the facility would be ready by the May 2014 start date.”Treetop claims Mississippi Power shouldhave known in 2013 the project could not be finished on time, and the company faked construction schedules.

Was Deloitte aware of these warnings as well as Wingo’s warnings and activities?

The troubling trends continued in 2017:

On January 20, 2017, a class-action complaint was filed against Southern Mississippi Power Company and a certain number of its officers by the Monroe County Employees’ Retirement System. The complaint alleged that the defendants made materially false and misleading statements regarding the Kemper IGCC in violation of key provisions under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended. Another lawsuit was filed on February 27, 2017.

Southern’s CEO Thomas Fanning stated in an earnings call on February 22, 2017, that the Kemper plant is not economically viable as a coal-burning power plant. With long-term gas prices being low, IGCC technology for the plant does not appear to be profitable (Zegart, 2017).

In May 2017, on Form 8-K and then on the first quarter 2017 10-Q report, Southern stated that the Kemper IGCC would be placed in service by the end of May 2017. On June 28, Mississippi Power suspended operations and start-up activities on the gasifier portion of the Kemper IGCC. In its 10-Q Report for the second quarter of 2017, Southern recorded a loss of $3.12 billion for the Kemper plant for the six months ended June 30, 2017. The loss was up to $3.155 billion for the nine months ended September 30, 2017, and then $3.362 billion for the entire fiscal year. By the end of 2019, the total cost overruns recorded as estimated losses were $6.264 billion.

On June 28, 2017, Mississippi Power Company announced that the work on its carbon capture portion of the Kemper Plant was being suspended. The plant will continue to burn natural gas. Three years behind schedule and $4 billion over its projected budget, Kemper concealed problems and greatly underestimated costs in the timeframe. Allegations of fraud and mismanagement abounded (Fehrenbacher, 2017).

Why did Southern Company abandon plans to open parts of the plant that involved converting coal into gas? JFIA points to several factors:

There are numerous reasons why Mississippi Power Company suspended efforts to start up the part of the plant using IGCC technology to convert coal into gas. These reasons include the overly complex technology, the operational risks due to equipment reliability, the difficulty of achieving high-capacity electrical production, quality of byproducts, and control integration. New environmental rules mandated by the Clean Air Act along with increased fracking practices that resulted in long-term cheaper natural gas made the case for IGCC harder to make (Wagman, 2017).

The Kemper Plant was way over budget and well behind schedule. The equipment failed to capture the promised amount of carbon dioxide and keep it out of the atmosphere. Fanning said that ending the coal operations was in the best interest of everyone (Fountain, 2017).In an Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis report, the conclusion is that the two IGCC projects, the Kemper plant in Mississippi and the Duke Energy plant in Indiana, prove the case against such investments because of the cost and time to build such plants and operate them.The plants are noncompetitive with gas plants (Schlissel, 2017b).

The Mississippi Public Service Commission, with new members elected in November 2015, voted to stop the project. The Sierra Club in Mississippi helped build public support for the change in the board members (Schlissel, 2017a).

Meanwhile, lawsuits are piling up, and attention is focusing on Deloitte:

In February 2017, two derivative lawsuits filed by Jean Vineyard and Judy Mesirov were consolidated in the U.S. District Court for Northern Georgia (Southern Company, 2018). The plaintiffs claim that the defendant, Southern Company, released false and/or misleading statements regarding the Kemper Plant. Additionally, the plaintiffs alleged that certain defendant employees were unjustly compensated and breached their fiduciary duties to the shareholders. The original settlement date appears to be March 10, 2022 (Southern Company Shareholder Derivative Litigation, 2022).

In May 2017, another derivative lawsuit was filed against Southern Company on behalf of the Helen E. Piper’s Survivor’s Trust in the Superior Court of Gwinnett County, Georgia (Southern Company, 2018). The plaintiff made similar claims to the former consolidated derivative lawsuits, alleging that certain directors and officers of Mississippi Power released false and misleading statements regarding the costs associated with the Kemper plant. Additionally, the plaintiff claims that the defendants did not institute proper internal control measures to avert potential adverse events.

Here is a key question at this point: Where were the auditors?

Deloitte has been Southern’s auditor since 2002; however, audit reports for the fiscal years 2011 through 2019 are under scrutiny in the newly filed class-action lawsuit. Throughout the debacle of the Kemper power plant as previously detailed, Deloitte provided Southern with an unqualified or “clean” audit opinion regarding its financial statements. Such an audit opinion indicates that the financial statements are presented fairly, in all material respects, in accordance with U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). As argued by the afore-described events relating to the Kemper power plant, one could conclude that the financial statements were not presented fairly according to GAAP. Deloitte’s incompetence fell not only on the annual financial statements, but also in its required review of the quarterly reports that Southern filed with the SEC.Where were the auditors?

In the Formby lawsuit, the plaintiffs argue that Deloitte did not follow the auditing standards of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), wherein Deloitte was required to perform audit procedures to obtain “reasonable assurance” as to whether Southern’s financial statements were free from material misstatement, whether caused by error or fraud (PCAOB AS 1001.02: General Principles and Responsibilities). . . . .

The lawsuit claims that Deloitte violated the tenets of due professional care and professional skepticism when conducting the Southern audits. The former requires the auditor to use “the knowledge, skill, and ability called for by the profession of public accounting to diligently perform, in good faith and with integrity, the gathering and objective evaluation of evidence.” (PCAOB AS 1015.07: General Principles and Responsibilities). The latter requires the auditor to maintain a questioning and critical mindset when evaluating evidence. The plaintiffs also allege that Deloitte apparently did not obtain an understanding of the nature of Southern’s business and regulatory environment in order to correct the misinformation presented in the financial statements regarding the expected completion date, the accounting method used to account for the costs of construction in process, rate revisions, and other related disclosures. For example, did Deloitte thoroughly investigate rate applications, labor difficulties, cost recovery estimates, the plant-construction timeline, significant internal reports, the delegation of oversight authority, percentage of completion calculations, or management involvement?

Surprisingly, Deloitte is still the auditor on Southern’s 2021 annual report (10-K). Given the plethora of evidence in the derivative lawsuits detrimental to Deloitte’s professed innocence, the accounting firm may have a difficult battle to wage in court, the resolution probably taking years, and will be settled out of court paying an undisclosed amount to lawyers andshareholders. More audit skepticism and use of some forensic techniques could have prevented the misinformation in the financial statements and the audit violations.