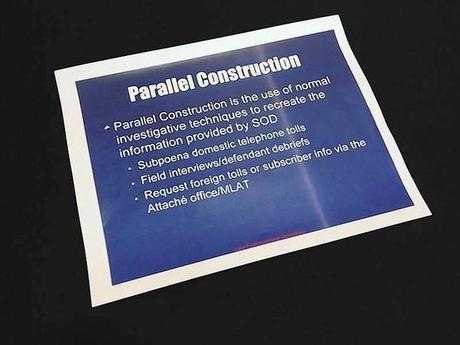

A slide from a DEA presentation

Suppose the Drug Enforcement Agency gets some information about illegal drug activity from a confidential informant of dubious reputation and they don’t want defense attorneys grilling the poor sap on the stand. What to do?

A series of articles recently published by Reuters reveals that since the early 1990s the DEA has employed a clever work-around.

Instead of using the actual source of the information, the DEA alerts law enforcement to pull over a particular car at a specified time and place and, sure enough, the trunk is full of powdered cocaine.

Here’s the kicker: the DEA doesn’t have to tell defense counsel how they knew to stop that particular vehicle. In fact, they don’t even have to reveal this information to local law enforcement, the prosecutor or the judge. Everyone is left in the dark and somehow that’s okay.

They call it “parallel construction”. In other words, you create a phony scenario ending in a drug seizure and you imply that the officers just happened to pull over the vehicle in question on a random hunch.

There is a simple word for this: “lying”.

This is precisely how the DEA convicted Ramsey Muñiz of engaging in a narcotics conspiracy in 1994, the year parallel construction was first used.

It took me months of sifting through the evidence in the case to figure out what was going on. I eventually concluded that hardly anyone associated with the case knew what was going on.

The DEA picked up a Mexican drug importer named Donacio Medina in Houston, then used him as bait to catch Ramsey Muñiz . The DEA told Medina that if he would implicate Ramsey Muñiz they would allow him to return to Mexico as a free man.

Now here’s the big question: was Muñiz really involved in a narcotics conspiracy with Medina, or did Medina simply create an entrapment scenario designed to make it appear that Muñiz was dirty? The important issue here is that no one associated with the DEA had any way of knowing if they could trust Medina.

Sifting through the discovery materials in the Muñiz case, would never know that the feds made a sketchy deal with a narcotics king pin. The judge who presided at trial wasn’t aware of the backstory. Even the DEA agents in Dallas who got a hot tip from their counterparts in Houston were completely in the dark. The assistant US Attorney who prosecuted the case had no clue what was going on.

And none of that mattered. So long as the DEA could produce a parallel construction in which Muñiz drove a car with drugs in the trunk it apparently didn’t matter. But what if (as I suspect is true) Muñiz just thought he was moving a car from one motel to another as a favor for a business partner? What if Medina invented a narcotics conspiracy to save his own skin? How would the feds possibly know? And what if the federal government supplied him with illegal drugs to make the deal work?

None of that mattered either. It’s not against the law to provide confidential informants with illegal drugs.

The investigative pieces published by Reuters were likely stimulated by recent revelations that the federal government, in its manifold manifestations, has been collecting oceans of data on law abiding citizens. But defense attorneys are interested in how parallel construction works in the war on drugs, as well they should.

If you don’t know how, and from whom, the “evidence” used to convict your client was obtained how can you determine the legitimacy of that evidence. In the Muñiz trial, for instance, Donacio Medina didn’t testify. In fact, his name never came up. The prosecution wasn’t aware of his relationship with the DEA in Houston.

But what if, as is almost certainly true, Medina was simply inventing the appearance of illegal behavior because that’s what it took to get him safely back to Mexico so he could continue running his narcotics syndicate? (You can find my full narrative on the Muñiz case here.) Surely defense counsel would relish the opportunity to put a narcotics kingpin on the stand. They could ask him about the deal he made with the feds. They could expose the man as a self-serving snitch. They could create reasonable doubt by suggesting an alternative (and exceedingly credible) theory of the “crime”.

In response to the shocking revelations in the Reuters articles related to parallel construction, defense attorneys are determined to put the federal government on trial. In the process, new revelations are sure to come to light. Perhaps the Department of Justice will launch an investigation.

To learn more about parallel construction, read on:

Defense lawyers to seek DEA hidden intelligence evidence

David Ingram and John ShiffmanReuters7:52 p.m. EDT, August 8, 2013 WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Criminal defense lawyers are challenging a U.S. government practice of hiding the tips that led to some drug investigations, information that the lawyers say is essential to fair trials in U.S. courts. The practice of creating an alternate investigative trail to hide how a case began – what federal agents call “parallel construction” – has never been thoroughly tested in court, lawyers and law professors said in interviews this week.Internal training documents reported by Reuters this week instruct agents not to reveal information they get from a unit of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, but instead to recreate the same information by other means. A similar set of instructions was included in an IRS manual in 2005 and 2006, Reuters reported.

The DEA unit, known as the Special Operations Division, or SOD, receives intelligence from intercepts, wiretaps, informants and phone records, and funnels tips to other law enforcement agencies, the documents said. Some but not all of the information is classified.

In interviews, at least a dozen current or former agents said they used “parallel construction,” often by pretending that an investigation began with what appeared to be a routine traffic stop, when the true origin was actually a tip from SOD.

Defense lawyers said that by hiding the existence of the information, the government is violating a defendant’s constitutional right to view potentially exculpatory evidence that suggests witness bias, entrapment or innocence.

“It certainly can’t be that the agents can make up a ‘parallel construction,’ a made-up tale, in court documents, testimony before the grand jury or a judge, without disclosure to a court,” said Jim Wyda, the federal public defender in Maryland, in an email.

“This is going to result in a lot of litigation, for a long time.”

LEGAL ACTION AHEAD

Kenneth Bailey, who defends drug cases in Sandusky, Ohio, said his firm was drafting new motions in light of the documents made public by Reuters.

“Evidence which could prove my clients’ innocence is being intentionally concealed,” Bailey said. “This is why criminal defense lawyers are working so hard to protect the (U.S.) Constitution, because the government is working so hard to destroy it.”

The Justice Department is reviewing the practice of parallel construction, and two high-profile Republican congressmen have raised questions about it.

DEA officials who defended the program on condition of anonymity said the practice was legal – and necessary to protect confidential sources and investigative methods. The Special Operations Division has used it virtually every day since the 1990s, they said.

Court decisions going back decades hold that prosecutors in the United States have a responsibility to turn over to a defendant any information that they or police have that is material to establishing the defendant’s guilt or innocence. The responsibility is known as the government’s Brady obligations, after the U.S. Supreme Court‘s 1963 ruling in the case of Brady v. Maryland.

The process of sharing evidence before trial or a guilty plea is known as discovery.

“This probably is a good wake-up call for us that we need to be more aggressive in our discovery requests, in digging a lot deeper and in not accepting that we’ve been told everything,” said David Patton, executive director of the Federal Defenders of New York. Like similar offices nationwide, his represents mostly the indigent.

Patton said information about how an investigation began may be highly relevant in certain cases because it bears on the credibility of government witnesses.

“Informants lie. They lie a lot,” he said. “You can’t competently or fully challenge the basis for a stop or search if the government’s hiding information about the real reason for the stop and search.”

HARD TO KNOW

One possible difficulty for defense lawyers is that they do not know which cases the DEA’s Special Operations Division had a hand in, so they do not have a list of cases in which to bring fresh challenges.

“Because they hid everything, you don’t know about it, and because you don’t know about it, you can’t make a specific allegation,” said A.J. Kramer, the federal public defender in Washington.

Investigative agencies, he said, ought to notify defense lawyers of the relevant cases, similar to a process the FBI is following to notify defendants in possibly thousands of cases in which hair samples might have been misused as evidence.

Defense lawyers will have to proceed without clear guidance from legal precedent, because there are no known cases in which judges ruled on whether defendants had a constitutional right to know about the tactic of parallel construction, according to lawyers, law professors and a search of electronic databases in Westlaw.

The term “parallel construction” was itself previously unheard of, these sources said, although there is voluminous discussion of related legal ideas.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled, for example, that police may stop a vehicle for any traffic offense, even if the offense was minor and police had a different motive for detaining the motorist, such as a tip. The 1996 ruling did not, however, address what rights a defendant would have if that original tip were kept secret.

Stephanos Bibas, a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania who writes about criminal evidence, said the U.S. system would benefit from judges getting more involved in reviewing such evidence.

“The pressure is all on the prosecutors and police to identify what’s relevant,” he said. “I don’t think that they are maliciously or deliberately hiding it very often. It’s more a tunnel vision problem that police and prosecutors can’t always see the way that the defense would use certain information.”

MEJIA CASE

When asked for the legal authority by which they shielded potential evidence from the defense, DEA officials cited the 2001 trial of Rafael Mejia, a Costa Rican citizen convicted in federal court in Washington.

The DEA declined to say whether parallel construction was used in the case, but records show that at trial neither Mejia, nor his lawyer, nor even the trial prosecutor knew the investigation had involved classified information.

They learned this only four years later as Mejia appealed his conviction, and a federal appeals court sent a notice that surprised lawyers on both sides. The court informed the lawyers that just days before the trial had begun in 2001, someone from a Justice Department narcotics office secretly approached the judge in his chambers to present him with classified evidence. The judge then made a secret ruling that Mejia was not entitled to this evidence because it was neither helpful nor relevant.

Such so-called ex parte decisions by judges on classified pretrial discovery issues are not unusual in terrorism cases, but prosecutors routinely file a related public notice to the defense about the existence of the secret filings. That did not happen in Mejia’s case.

The notice the appeals court sent the Mejia trial lawyers asked them each to address whether the information would have been relevant at trial. The court asked the lawyers to do this without disclosing what the classified information actually was. Defense lawyer H. Heather Shaner said the request felt Kafka-esque.

“I didn’t know about the information at trial and on appeal I couldn’t access it,” she recalled. “It made me irrelevant as a lawyer.”

The trial prosecutor, Robert Feitel, said he was as surprised as anyone to learn about the secret evidence. Now a defense lawyer in large drug cases, Feitel said he routinely tries to frame his requests for government evidence to include potential classified information whenever he believes intelligence intercepts or foreign wiretaps might have been used.

“I know that 99 percent of the time that happens there will be something relevant,” he said, “and I know that any good defense attorney would want to know about evidence that came through SOD.”

(Editing by Howard Goller and Doina Chiacu)