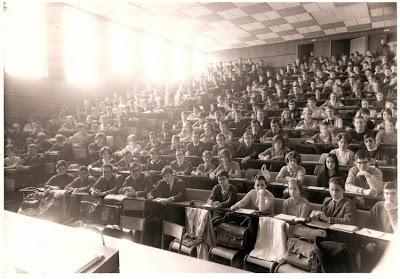

France has 83 state-supported universities and well over a million undergraduate students in university. After visits over several years to one of these universities and conversations with faculty and students, however, I have come away with some troubling impressions, especially in the humanities. The crux of the apparent problem is a pervasive lack of concern for undergraduate students' learning outcomes on the part of the universities and many of the regular faculty.

Part of this problem derives ultimately from a chronic lack of funding for the universities. Facilities on many campuses are decrepit, and the ratio of students to faculty is quite high. Students are admitted to the university and are charged very low tuition; but sufficient public resources are not made available to allow the university to offer them a high-quality, challenging education.

Another part of the problem is an over-emphasis on research over teaching. Research achievement is certainly an important national goal. But there is a degree of research fetishism that seems sometimes to overwhelm the other values of the university in France, including quality of teaching and learning. This over-emphasis on research within the university is found at the level of the ministry. And it seems to percolate downward as well, to individual campus administrations and to individual faculty. The impression one gets is that only research accomplishment is valued, and there is very little value given to effective teaching, either institutionally or individually. High-prestige research publications are the ticket for career advancement for the faculty member; and nationally visible research achievement is the coin of the realm for university leaders. This value scheme leaves out the undergraduate student almost entirely. But this gives woefully short shrift to the project of creating the next generation of creative, skilled, rigorous thinkers who will constitute the main source of innovation and new knowledge in the France of tomorrow. Currently the universities do not appear to be succeeding in focusing on this crucial task.

And then there is the problem of the turbo prof. This is a very broad phenomenon in the university world of France today that was largely created by the extension of the TGV network of fast trains connecting many secondary cities to Paris with 90 minute journeys. This has helped create the phenomenon of the "turbo prof" -- academics who live in Paris and commute to Tours, Dijon, Strasbourg, or other regional centers. There is a long history of French academics preferring Paris to the regional cities. But now it is possible to live in Paris and spend a day and a half on the regional campus where the academic has an academic appointment.

This phenomenon would not be troubling if the turbo prof kept up his or her part of the bargain: committed teaching, adequate time on campus to advise and assist students, and a reasonable degree of involvement in the intellectual and institutional life of the university. But this is all too often not the case, it appears. Instead, the amount of time spent on the university campus is often reduced to a two-day period of intensive lecturing. The prof travels from Paris on a Monday morning; reaches the campus by 11:00 am; lectures six hours on Monday; stays in a pied-a-terre or hotel room Monday night; lectures another six hours on Tuesday; and returns to Paris in time for dinner on Tuesday evening. It is easy enough to forget about those undergraduates in Tours, Strasbourg, or Dijon by the time the TGV slides into the Gare de Lyons or the Gare de Montparnasse or the Gare de l'Ouest.

This is very worrisome for the economic and civic future of France. University is a time during which students need to be stretched, challenged, and deepened in their intellectual capacities. But this isn't likely to happen when they have essentially zero contact with faculty, very limited writing assignments, and a very low sense of accountability for their progress on the part of the university.

This is also a hazardous reality for the permanent faculty of these universities. If it becomes apparent that their very limited efforts in their teaching roles make almost no difference in the process of development and maturation that their students achieve, then it is a very short step to concluding that their services are not needed. The few who are genuinely important research scholars may find alternative employment in research institutes, of which France has a fair number. But the idea of a teacher-scholar will be dead. And the next rank of less accomplished researchers will need to look for work outside of academia -- not a very encouraging prospect in France today.

The institutions governing higher education in France need to take these problems seriously. Universities need to refocus their attention on effective, transformative undergraduate education. Faculty need to be re-enculturated to give sincere adherence to the importance of their teaching responsibilities and contact with students. The turbo profs need to extend their work weeks on their regional campuses to a reasonable level -- at least three full days and preferably four. And the Ministry of Higher Education and Research needs to impose real standards of accountability on universities and departments, along the lines of the accreditation processes that exist in North America. And it goes without saying -- those accountability standards need to be focused on the primary values of the university, not the market value of this degree or that.

It is ironic to me that the sociology of education is a much more prominent part of the sociology profession in France than it is in the United States. Much attention has been given to the effects that the educational system has on class stratification, beginning with Bourdieu and Passeron, Les Heritiers: Les etudiants et la Culture, and extending through Mohamed Cherkaoui's École et société : Les paradoxes de la démocratie (French Edition). And yet I haven't been able to locate anything that focuses on the question of educational quality, the educational progress that undergraduates make, and the institutional and individual practices that interfere with educational progress in the universities.

Here is an OECD quality assessment report compiled in cooperation with Universite Louis Pasteur in Strasbourg (link). This document has many of the dimensions of an accreditation report in North America. And it illustrates several of the problems mentioned above. The report gives substantially more attention to research activities than teaching effectiveness; the university's response to this issue when raised in 1985 was essentially nil; and the one effort at implementing measures of teaching quality assessment that was undertaken -- student surveys of educational satisfaction -- was evidently discontinued. The report highlights continuing issues having to do with the effectiveness of undergraduate education: "the excellence of teaching in the postgraduate cycle and the shortcomings of the other cycles, with emphasis on the lack of performance indicators, especially as regards graduate employment; ...".

Here is a recent news story on the funding issues in French universities (link).

French readers -- what are your observations about undergraduate education in French universities?