It’s always exciting to see creativity and craft come together. Bespoke shoemaker Nicholas Templeman is coming to the US this month, starting Friday, October 9th. He’ll be visiting New York City, Boston, Chicago, and San Francisco. To prepare for his tour, he’s put together a collection of eight samples – ranging from the sort of conservative oxfords he used to help make for John Lobb of St. James, to dandier styles, such as a bright-colored button shoe.

My favorites from him are somewhere in between – styles that have a bit more flair than a traditional oxford, but are conservative enough to wear with a simple suit or sport coat. The adelaides above, for example, are beautifully made from a smooth box calf, and then distinguished with hatch grain facings and counters. A bit of interesting history: box calf used to refer to a hand curried and boarded leather – called so either because the object they used to prepare the leather was box-like, or because the process created box-like markings. It was supposedly done to help soften the leather, but nowadays, that’s done through the tanning process, so the term box calf just refers to a smooth (usually black) leather, like you see above.

I also like this five-eyelet Norwegian, made from a waxed calf and decorated with a beautifully finished apron. The stitching you see on the apron was executed with a slightly modified saddle-stitch. Whereas traditional saddle-stitching is done by passing two needles through the same hole (seen here in this Hermes video), Nicholas wove a piece of thread through each loop before pulling the stitching tight. The result is this beautifully decorative stitch that can be used on any material – including suede, which typically doesn’t take pie-crust aprons very well, at least compared to calf, because of the looser packing of the fibers. Possibly nice if you want some hand detailing on a Norwegian apron, but have been unsatisfied with suede Edward Green Dovers.

It’s a bit hard to see in the photos, but the shoes were also finished with a squared waist, which is what you would typically see on factory-made footwear (most bespoke shoes are finished with a beveled waist, where the waist is curved for a refined look). Squared waists, however, are a bit better suited to some styles. “Country shoes, for example, are better with squared waists,” says Nicholas. “They’re designed for when you’re sitting on a horse, so a curved waist wouldn’t be practical, although a customer can of course get anything he wants.”

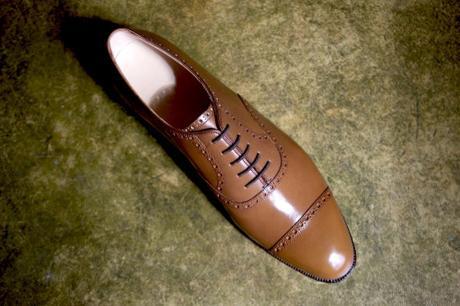

Next up, a Paris monk, which is defined by its straight seams along the quarters. If you look closely at the sides of the shoe, you’ll notice that the seams come straight up from the welt, leading to the buckle. This differs from other single monkstraps, which have angled side seams, like you’d find on a derby.

It’s unclear where the name Paris monk came from, although one possibility is the slightly more Continental style. The toe here looks a bit more elongated than a traditional English shoe, but not because the toe is actually long. Rather, it’s because the strap and seams have been placed further back. Like with the adelaides at the top of this post, these monks have been made from box calf.

Finally, some chukka boots that were partly inspired by Japanese shoemaker Clematis. The back here is a little higher and the vamp nicely curves up. If made for a customer, Nicholas tells me that the laces would probably have to be set a little lower for comfort, although he kept them high on this sample for stylistic purposes. The curvy, decorative stitching on the quarters help break up that expanse of leather.

A bit of fun history: ever wonder why shoemakers stamp their name on their soles? It’s not because they’re hoping for a bit of advertising every time you cross your legs. The practice apparently started long ago in London, when there were dozens of bespoke shoe firms and everyone relied on the same network of outworkers. Nicholas explains:

That stamp on the sole is what firms used to do when the trade was a lot busier. You had work and materials going to outworkers here, there, and everywhere, so an unscrupulous maker might swap your high-grade Croggans outsole leather for some tooty, rough stuff he had laying around. You stamped your mark on the soles and top heels to make sure the same stuff came back! Today, it’s just a nice bit of history to maintain, of course.

Nicholas does his imprinting by hitting the leather really hard with a hammer and carpenter’s handstamp, although the process isn’t as simple as it sounds. “With Lobb, there are just four letters, so you don’t have to worry about the angle too much. But I have this terribly long name, so sometimes it takes a few tries.” We all work with what we’re born with, I suppose.

If you’re interested in seeing Nicholas on this trip, shoot him an email soon. He’s arriving in New York City on Friday and will be making his way towards San Francisco over the next week. He’s also offering a small introductory discount, given that it’s his first time touring the country as an independent shoemaker (although he’s come before as a representative of Lobb). Prices aren’t cheap, but they’re lower than other London makers. You can see his travel schedule here.