If you haven’t been following 3:AM’s interview series, you should. The Brian Leiter interview was one of the most cogent assessments of philosophy I’ve read in years, and the recent Eric Schwitzgebel interview is on par. Both reward close reading and deserve extended comment, but I want to touch briefly on Schwitzgebel’s assessment of the relationship between what he calls “common sense” and metaphysics:

My suggestion is this: Common sense is incoherent in matters of metaphysics. There’s no way to develop an ambitious, broad-ranging, self-consistent metaphysical system without doing serious violence to common sense somewhere. It’s just impossible. Since common sense is an inconsistent system, you can’t respect it all. Every metaphysician will have to violate it somewhere.

Common sense, as Schwitzgebel frames it, has “everyday practical interactions with the world.” In broad evolutionary terms, this is the sense formed over millions of years in mostly African environments. The brain-mind which gives rise to “common sense” evolved to handle all sorts of practical and social problems, none of which have anything to do with metaphysics. It is not surprising, therefore, that there is a mismatch between the commonsense mind and the metaphysical mind.

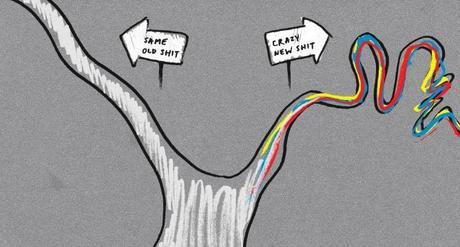

Left Fork: Ancestral Mind/ Right Fork: Metaphysical Mind

Knowing that the mind which evolved in ancestral environments is capable of metaphysics doesn’t mean it is good at metaphysics. And if we take the history of metaphysics as a guide or proof, it doesn’t appear we have made much progress or come into closer contact with the singular “Truth” which seems to be its goal.

For me the more fundamental question revolves around what Schwitzgebel calls an “ambitious, broad-ranging, self-consistent metaphysical system.” Why is this desirable? Why is it needed? What would it do?

The quest for a single consistent system seems to be a psychological need which finds its greatest expression among metaphysicians and religionists. I’m not sure why such a system is good or needed for the rest of us.

Why not have one “system” for one class of problems and another “system” for another class of problems? There are different approaches to different problems. What causes the impulse towards unification, systematization, and consistency? Like Nietzsche and Emerson, I’m suspicious of systematizers and consistency.

Although systematizers are often associated with metaphysics-religion, they also appear in science-atheism. The latter, with whom I often sympathize, have an unfortunate tendency to overstate the case and overestimate what is known. For them, Schwitzgebel has this crazy advice:

You can’t do an empirical study, for example, to determine whether there really is a material world out there or whether everything is instead just ideas in our minds coordinated by god. You can’t do an empirical study to determine whether there really exist an infinite number of universes with different laws of physics, entirely out of causal contact with our own. We’re stuck with common sense, plausibility arguments, and theoretical elegance – and none of these should rightly be regarded as decisive on such matters, whenever there are several very different and yet attractive contender positions, as there always are.

I conclude that regarding the fundamental structure of the universe in general and the mind-body relation in particular something that seems crazy must be true, but we have no way to know what the truth is among a variety of crazy possibilities. I call this position “crazyism.”

Crazyism appears to have great promise; I predict that positivism writ large will eventually prove it true.