The country house enjoyed a golden age at the same time that the telephone network was developing. In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone. That same year, Tivadar Puskas came up with the idea of a telephone exchange. W H Preece, Engineer-in-Chief of the Post Office, brought the first pair of telephones to Britain in July 1877; the first long-distance calls in the country came the following year, when Bell himself demonstrated the telephone to Queen Victoria at Osborne House. The Telephone Company Ltd was formed, with the first trial of commercial long-distance calls taking place on 1 November 1878; the company launched with fewer than ten subscribers. By the end of 1879, it had 200. However, the telephone was still something used primarily for business, with exchanges only in major cities.

At the end of 1880, the judgment in Attorney-General v Edison Telephone Company of London Ltd saw telephones placed under Post Office control, on the basis they were a form of telegraphy. The Post Office nonetheless licensed other companies for some years, as well as opening further exchanges by converting telegraph exchanges. A national network was developing, and 1884 saw the opening of public call offices where members of the public could make telephone calls. These soon evolved into telephone boxes. Perhaps an even more significant marker of the increasing use of telephones for personal calls was the introduction of cheaper calls outside business hours in 1903.

Thus the telephone quickly took a key role in modern communications. That is symbolised rather nicely by two 1890s putti having a telephone conversation outside the former Astor Estate office at 2 Temple Place!

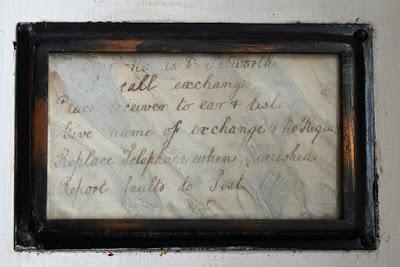

Country estates were often significant businesses in their own right, so having telephones made sense. Thus there is a telephone in the estate office at Petworth, complete with instructions. 'To call exchange place receiver to ear and listen. Give name of exchange & no. required. Replace telephone when finished. Report faults to Post Office.' (That last instruction may tell us something about the reliability of the system.) Another factor was that these monied households could afford the subscriptions and call costs - and had similarly affluent associates, friends and relatives to receive the calls.

These households were also large enough to benefit from internal telephone systems. They offered a more discreet and efficient alternative to servants' bells: thus Petworth's connected to the kitchen quarters, with lines labelled by room name.

Throughout the twentieth century, the network expanded, technology improved and prices became more affordable - but it took time. Telephone calls remained expensive in the 1930s, when the Courtaulds built their home at Eltham Palace. They had a private internal telephone exchange, installed by Siemens; but guests had to make external calls from a payphone.