The Book of Daniel is one of the most contested writings in the Bible. Atheists understand the significance of Daniel and attack it with regularity.

Here’s a note on the Secular Web about Daniel:

“The prophecies of the Book of Daniel have fascinated readers and created controversy for the past two thousand years. Evangelical Christians believe that the prophet Daniel, an official in the courts of Near-Eastern emperors in the sixth century BC, foretold the future of the world from his own time to the end of the age. Actually, the book was written in Palestine in the mid-second century BC by an author who expected God to set up his everlasting kingdom in his own near future, as we read in the mainline commentaries and Bible dictionaries.

We pointed out in our last article that many atheists attack Daniel as being written centuries after King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon and King Cyrus of Persia actually ruled. They know that a late dating of Daniel would bring Daniel’s visions and prophecies into question and would also cause problems with the New Testament texts where Jesus uses the term ‘Son of Man’ (from Daniel 7:13) for Himself.

I would have agreed with atheists 45 years ago when I was also an atheist. However, that was before I looked into the evidence for the historical accuracy of the Book of Daniel.

What’s In A Name?

“Belshazzar the king made a great feast for a thousand of his lords, and drank wine in the presence of the thousand.” Daniel 5:1

The name ‘Belshazzar’ is an interesting one as we look into Babylonian history. As pointed out by the Encyclopedia Britannica:

“Belshazzar had been known only from the biblical Book of Daniel (chapters 5, 7–8) and from Xenophon’s Cyropaedia until 1854, when references to him were found in Babylonian cuneiform inscriptions.” Belshazzar – King of Babylonia, Encyclopedia Britannica

Ancient historians (e.g. Berossus, Polyhistor) listed Nabonidus as the last king of Babylon with no mention of Belshazzar. It wasn’t until almost two thousand years later that archaeologists found evidence that the Bible’s listing of Belshazzar as a king of Babylon was correct.

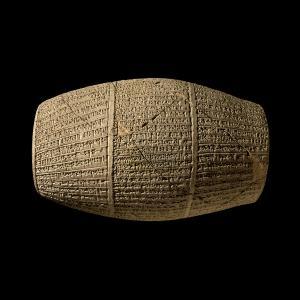

British archaeologist John George Taylor worked in Iraq in the middle of the 19th century on behalf of the British Museum. Taylor discovered clay cylinders at the ancient ruins at Tell el-Muqayyar (Ur). Nabonidus mentions his son Belshazzar by name on the cylinder:

“As for me, Nabonidus, king of Babylon, save me from sinning against your great godhead and grant me as a present a life long of days, and as for Belshazzar, the eldest son -my offspring- instill reverence for your great godhead in his heart and may he not commit any cultic mistake, may he be sated with a life of plenitude.” The Nabonidus Cylinder from Ur

Cylinder of Nabonidus, Courtesy The British Museum

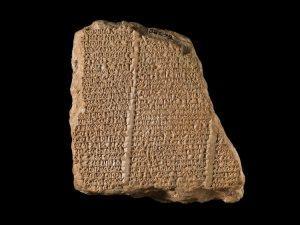

Assyriologist Hormuzd Rassam, who was born in Mosul, Iraq (Ottoman Mesopotamia) in the early 19th century spent much of his career working for the British Museum. One of his crowning achievements was excavating the temple of the sun god Shamash in the city of Sippar (in southern Iraq) where he discovered about 50-thousand cylinders and tablets. One of the cylinders became known as the Cylinder of Nabonidus. It’s dated to about 555-540 BC. Nabonidus details his time away from Babylon to rebuild pagan temples in Harran. This is supported by a 6th century BC cuneiform tablet known as the Nabonidus Chronicle. It ‘chronicles’ the king’s activities during his reign and shows that Nabonidus spent many years in Tema while ‘the crown prince” was in ‘Akkad’ (Babylon?) with his officials and army. The fact that the king’s officials and army were with the crown prince is more evidence that Belshazzar was in a position of co-regeancy with his father.

Belshazzar’s position as the number 2 in the kingdom would explain why he offered the interpreter of the writing on the wall the position of ‘the third ruler in the kingdom’ (Daniel 5:7). However, that raises the question about why Daniel never mentioned King Nabonidus. A simple explanation may be that Daniel didn’t mention Nabonidus because Nabonidus was not involved in the event Daniel described. From what we read in the Nabonidus Chronicle, Nabonidus lived in Tema for most of his 17-year reign. Tema was located hundreds of miles southwest of Babylon and the Chronicle related how Nabonidus did not go to Babylon often. He missed many of the official and religious ceremonies during those years. Belshazzar, the ‘crown prince,’ was with the king’s ‘officials and his army’ and would have acted officially in his father’s stead.

Verse Account of Nabonidus, Courtesy of British Museum

An ancient text known as the Persian “Verse Account of Nabonidus” (dated to the latter part of the 6th century BC) states that Nabonidus entrusted his army and ‘kingship’ to his oldest son [Belshazzar] and marched a long distance on a path to a distant region ‘deep in the west.’ The Verse Account goes on to say that Nabonidus killed the ‘prince of Tem’ and took possession of the area. The text says Nabonidus ‘made the town beautiful’ and ‘built there a palace like the palace in Babylon.’

Based on the evidence found in the various ‘chronicles,’ it would seem that Belshazzar would have been the ruler that most people in Babylon would have known on a daily basis since Nabonidus lived hundreds of miles away and rarely returned to Babylon.

Here’s a question that seems to be in favor of Daniel writing the Book of Daniel in the latter part of the 6th century BC. Since Belshazzar was not listed on any known Babylonian ‘kings list,’ how would someone living in the 2nd century BC know to list him as a king in the 6th century? The most plausible explanation seems to be that the author of Daniel knew about Belshazzar because he actually lived during the 6th century BC.

What about Daniel’s statement that Nebuchadnezzar was Belshazzar’s ‘father’?

“While he tasted the wine, Belshazzar gave the command to bring the gold and silver vessels which his father Nebuchadnezzar had taken from the temple which had been in Jerusalem, that the king and his lords, his wives, and his concubines might drink from them.” Daniel 5:2

We’ve already seen that Nabonidus was Belshazzar’s father, so how could Nebuchadnezzar also be his father?

Archaeologists have found that the Babylonian King List dates back as far back as the early Amorite city-states to the middle part of the 20th century BC and is related to its predecessor known as the Sumerian King List. The Babylonian Empire began in the Middle Bronze Age (MBA) during the latter part of the 19th century BC. Nabonidus and Belshazzar ruled at the end of the 11th Dynasty, often referred to as the Neo-Babylonian (also known as Chaldean and Akkadian Dynasty).

Nabopolassar took control of Babylonia from the Assyrian King about 626 BC. The Chronicle Concerning the Early Years of Nabopolassar (ABC 2) and the Chronicle Concerning the Late Years of Nabopolassar (ABC 4) detail his years as King of Babylon. Cuneiform Tablet ME 21901 in The British Museum summarizes many of the events concerning Nabopolassar’s time as king.

Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabopolassar, became king after his father died in 605 BC. Amel-Marduk, son of Nebuchadnezzar, became king after his father died in 562 BC. Babylonian priest and historian Berossus wrote that Amel-Marduk was murdered in a plot by his brother-in-law Neriglissar. Neriglissar died four years later and his young son Labashi-Marduk became king, but was quickly overthrown by Nabonidus.

Even though the time from when Nebuchadnezzar died (562 BC) to when Nabonidus became king (556 BC) was only six years, the question remains why Daniel would write that Nebuchadnezzar was Belshazzar’s ‘father.’

We know from archaeological discoveries that Nabonidus was Belshazzar’s father, but who was Belshazzar’s mother? Some scholars (**) believe that a woman named Nitocris may have been the daughter of Nebuchadnezzar, wife of Nabonidus and mother of Belshazzar. If that’s true, then Nebuchadnezzar would have been Belshazzar’s grandfather. It was common in ancient times to refer to a grandfather, great-grandfather or even more distant ancestor as someone’s ‘father.’

This is particularly interesting in light of Jeremiah’s prophecy during the 7th century BC that many nations (including Judah) and great kings (including Jehoiachin) would serve Nebuchadnezzar ‘and his son and his son’s son.’ That could very well have meant Belshazzar, whose father may have been the son-in-law of Nebuchadnezzar (Jeremiah 27:1-11)

** Raymond Philip Dougherty was the William M. Laffan Professor of Assyriology and Babylonian Literature at Yale University. His specific area of expertise was the Neo-Babylonian era, including its history and cuneiform documents. Professor Dougherty wrote a book in 1929 called Nabonidus and Belshazzar, a Study of the Closing Events of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (Yale University Press). On page 43 of the book, Dougherty wrote this:

“Enough evidence has been presented to make it apparent (a) that the Labynetus of Herodotus was Nabonidus, (b) that Nitocris was the wife of Nabonidus, and (c) that their son was a man of authority in the kingdom. Considerations of strong corroborative value may be presented. “

We will read more about the part Nitocris may have played in Daniel’s account as we continue our investigation – Convince Me There’s A God.

Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.