Sobering results from Wingen et al.:

Prolonged stress can have long-lasting effects on cognition. Animal models suggest that deficits in executive functioning could result from alterations within the mesofrontal circuit. We investigated this hypothesis in soldiers before and after deployment to Afghanistan and a control group using functional and diffusion tensor imaging. Combat stress reduced midbrain activity and integrity, which was associated to compromised sustained attention. Long-term follow-up showed that the functional and structural changes had normalized within 1.5 y. In contrast, combat stress induced a persistent reduction in functional connectivity between the midbrain and prefrontal cortex. These results demonstrate that combat stress has adverse effects on the human mesofrontal circuit and suggests that these alterations are partially reversible.

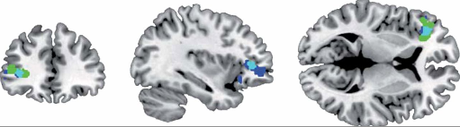

Legend (click figure to enlarge) - Combat stress reduces functional connectivity of the midbrain with the lateral prefrontal cortex. The reduction from baseline to short-term follow-up is presented in blue. The persistent reduction from baseline to long-term follow-up at 1.5 y after military deployment is presented in green. The overlap between the short-term and long-term effects is presented in cyan.A bit more expanded summary in their discussion:

These results show that the adverse effects of combat stress on sustained attention are related to functional and structural changes in the midbrain. These alterations normalize within 1.5 y in soldiers without psychiatric complaints, which may explain why long-term cognitive deficits following combat are mainly observed in soldiers with posttraumatic stress symptoms. In contrast to the reversible effects on the midbrain itself, its reduced interaction with the prefrontal cortex persists for at least 1.5 y. Taken together, these results suggest that the human brain can largely recover from the adverse effects of stress, supporting the view that neural plasticity in response to prolonged stress is adaptive. However, the results also reveal long-term changes within the mesofrontal network that may increase the vulnerability to subsequent stressors and lead to long-lasting cognitive deficits.