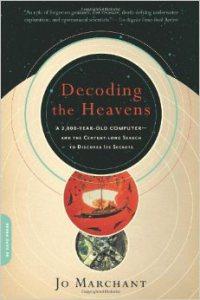

In a museum in Athens sits a device chock-full of gears and cogs and dials. Indeed, it looks quite a bit like the movement of a pre-digital clock. This particular object, known as the Antikythera Device, is what would sometimes be labeled an “out of place artifact” were its provenance not so well attested. History doesn’t always play fair. Jo Marchant’s Decoding the Heavens: A 2,000 Year Old Computer—And the Century-Long Search to Discover Its Secrets tells the fascinating story. Discovered by sponge-divers blown off course by a storm in 1900, a sunken ship at Antikythera became the first ever site of a ship-wreck excavation attempt. Even today underwater archeology presents numerous challenges, but in the turn of the previous century, even land-based archeology was a kind of glorified treasure hunt rather than an attempt to reconstruct ancient history. As the divers visited and revisited the site into 1901, they discovered ancient Greek statues that are among the best preserved from the ancient world. They also found the corroded box of gears that nobody really noticed for several months.

In a museum in Athens sits a device chock-full of gears and cogs and dials. Indeed, it looks quite a bit like the movement of a pre-digital clock. This particular object, known as the Antikythera Device, is what would sometimes be labeled an “out of place artifact” were its provenance not so well attested. History doesn’t always play fair. Jo Marchant’s Decoding the Heavens: A 2,000 Year Old Computer—And the Century-Long Search to Discover Its Secrets tells the fascinating story. Discovered by sponge-divers blown off course by a storm in 1900, a sunken ship at Antikythera became the first ever site of a ship-wreck excavation attempt. Even today underwater archeology presents numerous challenges, but in the turn of the previous century, even land-based archeology was a kind of glorified treasure hunt rather than an attempt to reconstruct ancient history. As the divers visited and revisited the site into 1901, they discovered ancient Greek statues that are among the best preserved from the ancient world. They also found the corroded box of gears that nobody really noticed for several months.

Marchant carefully unravels the slow process of discovery, acclaim, and forgetfulness that accompanied learning about this highly advanced computer. As with many other important finds, World Wars I and II led to distractions that made history somewhat less appealing than killing millions and then trying to recover from the damage. (The Ugaritic tablets, as I’ve often suggested, suffered a similar forgetfulness for being found at the wrong time.) As scholars, usually only one or two in a decade, began to notice the Antikythera mechanism, it became very much an object out of time. A sophisticated computer for calculating the movement of the sun, moon, and planets, the device could also show the phases of the moon, predict eclipses, and keep track of the Saros, Metonic, Exeligmos, and Callippic Cycles (18, 19, 54, and 76 years in duration, respectively). These cycles accounted for the adjustments needed by leap years and other fixes in the modern calendar. I can’t even keep track of Daylight Savings Time.

Adding to the mystery and drama, the Antikythera Device dates from the first century BCE, a time confirmed by radiocarbon dating and the presence of coins found on the ship. It is unknown who made it, but the influence of Archimedes is implicated. A similar device would not be known for another 1500 years with the beginnings of the Early Modern Period. The Roman Empire, which held power in the Mediterranean world at the time, was on its way toward the legendary decadence that would lead to its inevitable fall. It seems that a culture based on military might had little use for academic devices that were literally centuries ahead of their time. History does not repeat itself precisely, but broad strokes may often reveal more than passing similarities. And for those who want to discover a computer than shouldn’t have been, Marchant’s book is an excellent introduction to how the wisdom of the ancients still keeps us guessing.