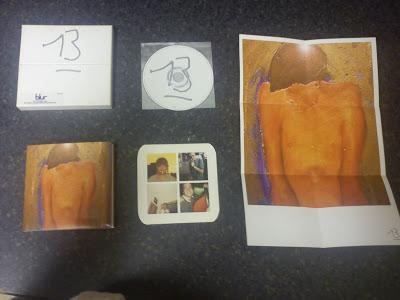

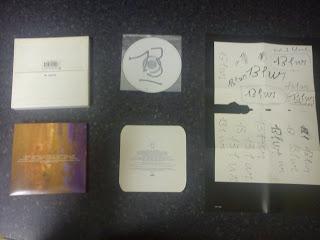

It's almost impossible to believe it, but Blur's sixth album '13' was released exactly 20 years ago today, on 15 March 1999.

It's almost impossible to believe it, but Blur's sixth album '13' was released exactly 20 years ago today, on 15 March 1999.The late 90's were a very interesting period in Blur's career. Their self titled 1997 debut saw a raw reinvention and a complete step away from the Britpop scene, replacing the lively English pop with a darker, rougher-edged, more inventive approach to making music. Despite alienating some of their casual fanbase, the 'Blur' album saw them regain a lot of critical respect and also helped the band become better known worldwide. By the late 90s, the Britpop party was officially over, but Blur's reinvention had kept them in the premier league of the UK's biggest names in music.

Wondering what direction the next Blur album was going to take was something that brought up many possibilities. Would they decide the experimenting was out of their system and return to writing catchy pop anthems again? After 'Song 2''s success would this be their lo-fi grunge punk album? It was confirmed that the record would be produced by William Orbit, a dance musician who had previously worked with Madonna on her 'Ray Of Light' album. Would this be Blur's dance album? Far from being littered with club anthems and trance beats, '13' would turn out to be a brave, dense, ambitious, weird, noisy and emotionally fragile piece of work that sounds even more incredible 20 years on than it did back then. Before its release the music press was alive with speculation about what the album, and when I first read about the album's first single, the band described it as a country-gospel song. When I first heard 'Tender' I realised that while it was indeed that, it was also a whole lot more.

I bought the single on its day on release from a record shop in Bath called Rival Records, and a few weeks later excitedly purchased '13' on the day it hit the shops. I recall hearing a few of the tracks previewed on Radio One in the week leading up to the album's release, but hearing the album in full was an utter revelation. I also instantly found it to be even more of a challenging listen than its predecessor, but after a while every single moment of '13' grew on me in a most rewarding way. With its gospel choir and inventive percussion (made up from planks of wood being banged against the studio floor), it's hard to imagine anything more uplifting than the joyously soulful 'Tender'. But this glorious opener was something of a red herring when it came to what the rest of the LP would sound like.

I bought the single on its day on release from a record shop in Bath called Rival Records, and a few weeks later excitedly purchased '13' on the day it hit the shops. I recall hearing a few of the tracks previewed on Radio One in the week leading up to the album's release, but hearing the album in full was an utter revelation. I also instantly found it to be even more of a challenging listen than its predecessor, but after a while every single moment of '13' grew on me in a most rewarding way. With its gospel choir and inventive percussion (made up from planks of wood being banged against the studio floor), it's hard to imagine anything more uplifting than the joyously soulful 'Tender'. But this glorious opener was something of a red herring when it came to what the rest of the LP would sound like. On the complete opposite end of the spectrum is the blistering 'Bugman' with its brutal guitar fuzz and pneumatic drill noise that descends into utter chaos before a stinging bassline and raucous riffage take things to a new level. 'Coffee And TV' was noticeably more pop than anything else but even the album's most accessible moment had an off kilter quality and a slightly weird feel to it, topped off with Graham Coxon's squealing, shredding guitar towards the end. Back then it sounded almost throwaway. Now, it's an essential part of '13' that adds some much-needed light relief and a great deal of charm. It's ironic that Coxon should pen the album's most melodic and accessible track, since his fondness for blistering guitar noise was key in the transformation of Blur's sound on '13' and the self-titled album released two years earlier. 'Coffee and TV' was written while Graham was struggling with his alcoholism, which had increased throughout the hedonistic 90s, with the guitarist reflecting on how he would unwind by watching television over a cup of coffee to take his mind off the booze.

'Swamp Song' is a sludgy monster, covered in heavy, muddy riffage, and indulging in the sort of reckless, chaotic fun that went on at the "party pad" that Damon Albarn and his Gorillaz co-creator Jamie Hewlett shared during the late 90s. It's The Fall doing Bowie doing Elvis, and it's a total blast. Much was said of the personal nature of the lyrics throughout the record, and revelatory they are indeed. Damon had been in a relationship with Elastica vocalist Justine Frischmann throughout the Britpop years, and the couple's break-up in late 1997 hit him hard. "That relationship just absolutely crashed. I mean, it really was a spectacularly sad end" he remembered. "It was the first time in my life that I'd been knocked for six emotionally. I'd been very lucky upto that point and had no real reason to explore that, so that's why it's happened now."

'Swamp Song' is a sludgy monster, covered in heavy, muddy riffage, and indulging in the sort of reckless, chaotic fun that went on at the "party pad" that Damon Albarn and his Gorillaz co-creator Jamie Hewlett shared during the late 90s. It's The Fall doing Bowie doing Elvis, and it's a total blast. Much was said of the personal nature of the lyrics throughout the record, and revelatory they are indeed. Damon had been in a relationship with Elastica vocalist Justine Frischmann throughout the Britpop years, and the couple's break-up in late 1997 hit him hard. "That relationship just absolutely crashed. I mean, it really was a spectacularly sad end" he remembered. "It was the first time in my life that I'd been knocked for six emotionally. I'd been very lucky upto that point and had no real reason to explore that, so that's why it's happened now."What wasn't so public at the time was Albarn's use of heroin. Suede and Elastica's problems with the drug was well-documented, yet people only found out years later that Damon was a regular heroin user from 1996 up until some point in the 2000s. In hindsight, the clues are all there: 'Bugman' refers to "the nodding dogs", with "chasing the bug" being a slang for smoking the drug in tin foil. 'Caramel' is said to hint at the color of heroin, the "I dose away" lyric in Trimm Trabb could be about a different kind of "hit" than the ones Blur were previously known for, and theories that the Damon-Justine break-up was down to heroin use are fueled by 'Trailerpark''s refrain "I lost my girl to the Rolling Stones". Those who did notice the drug references at the time assumed that they were all pointing to Frischmann, when it's very likely that Albarn was opening up about his own state of mind.

Discovered as a demo on a cassette seven years after it was recorded, the solemn, unsettling '1992' is a musical relative of 'Sing' from their debut album 'Leisure', which seems to lyrically address themes of infidelity, while the dark, sombre music aches with shattered emotions and torn hearts as anguished guitars scratch and tear away at the surface. Meanwhile, blazing rave-up 'B.L.U.R.E.M.I' goes truly berserk with its punk riffs, deranged helium voices and some wild, bizarrely-placed melodica. Following one of the short instrumental seques that are found on a few occasions throughout '13', the album's magnificent centrepiece 'Battle' arrives. 7 minutes 42 seconds of extraordinary music that showcases the four members of Blur reaching a technical peak. It's the sound of beauty and decay, pulling off the feat of being both noisy and relaxing at the same time, pairing blissful ambience with more of the incredible sounds that emerge from Coxon's distorted guitar, as fluid keys ring out to create an otherworldly atmosphere. It's a fine example of the layered sound William Orbit brings to the record.

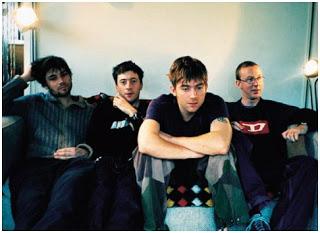

Many of the songs were pieced together from jam sessions, and the four members of the band were rarely in the studio together at the same time. Tension in the group was running high during the recording sessions, with Orbit recalling "There was a battle between Damon's more experimental direction, and Graham's punk one, and Graham prevailed. If that tension had been growing on previous LPs, it came to a head here." Meanwhile, drummer Dave Rowntree later revealed "Things were starting to fall apart between the four of us. It was quite a sad process making it. People were not turning up to the sessions, or turning up drunk, being abusive and storming off." Coxon admitted later "I was really out there around 13, which made for some pretty great noise but I was probably a bit of a crap to be around."

Many of the songs were pieced together from jam sessions, and the four members of the band were rarely in the studio together at the same time. Tension in the group was running high during the recording sessions, with Orbit recalling "There was a battle between Damon's more experimental direction, and Graham's punk one, and Graham prevailed. If that tension had been growing on previous LPs, it came to a head here." Meanwhile, drummer Dave Rowntree later revealed "Things were starting to fall apart between the four of us. It was quite a sad process making it. People were not turning up to the sessions, or turning up drunk, being abusive and storming off." Coxon admitted later "I was really out there around 13, which made for some pretty great noise but I was probably a bit of a crap to be around."The mesmerising 'Mellow Song' switches from bare voice and acoustic guitar to a slow, humpy rhythm topped off with an addictive bassline and more of that melodica, an instrument that Albarn makes superb use of on '13'. The middle part turns into a magnificent psychedelic circus, but plays well with the moody acoustic grunge verses. 'Trailerpark' instantly conjures up images of dirty ghetto streets with its tone of squallor. It was originally premiered a year previously at the band's 1998 headline set at Glastonbury. The half-rapped delivery is again highly reminiscent of The Fall's Mark E. Smith, especially so in its live incarnation, while his deepest and most solemn tone is saved for the chorus. Style-wise its a clear precursor to the hip-hop flavours of Albarn's hugely successful Gorillaz.

However, the vocalist's most emotional performance is reserved for the desolate ambience of 'Caramel'. It almost feels like you shouldn't be hearing something so personal, but clearly this song couldn't have existed any other way. Ambient textures flow into one another dramatically as the overwhelming heartbreak is exhibited so openly and sincerely. 'Trimm Trabb' is made up of another rhythm formed from odd percussion sounds and a rather grungy acoustic riff, before exploding like a nail bomb at the end as Coxon unleashes a torrent of devastating guitar. The candid, spacious 'No Distance Left To Run' again finds Damon at his most fragile and soulful, complimented by an effectively minimal arrangement. '13' concludes with the lovely oddity 'Optigan 1, a short Joe Meek-esque instrumental with a nod to some of the fairground and end-of-pier vibes that featured on a few 'Parklife' tracks, but this time far more grainy, sounding like some long lost 78 record from the past.

When '13' was released I had been a Blur fan for five years and was always pleased to see them taking new directions, but this album did take a while to sound like the seminal piece of work that it represents today. 20 years later '13' is a record that resonates even more now than it did back then, and stands as perhaps the most essential Blur album. It cemented Blur's legacy and reputation as one of Britain's all-time greatest musical exports. The LP scored Blur their fourth consecutive Number 1 album in the UK, and was nominated for the Mercury Prize. Years later, it's regarded as one of the group's finest works.

When '13' was released I had been a Blur fan for five years and was always pleased to see them taking new directions, but this album did take a while to sound like the seminal piece of work that it represents today. 20 years later '13' is a record that resonates even more now than it did back then, and stands as perhaps the most essential Blur album. It cemented Blur's legacy and reputation as one of Britain's all-time greatest musical exports. The LP scored Blur their fourth consecutive Number 1 album in the UK, and was nominated for the Mercury Prize. Years later, it's regarded as one of the group's finest works.The band slowly fell apart soon after, with Graham departing in 2001, leaving a three piece to record 2003's underwhelming 'Think Tank'. When the four piece returned in 2009 for a series of triumphant shows, the songs from '13' that once sounded a bit odd now sounded like real anthems... Happy birthday to a brave, ragged, noisy and beautiful album.