It’s a wonder us previous generations managed to survive without a “recess coach”.

NYPost: The city has hired “recess coaches” to teach kids how to play nicely. The Department of Education has forked over $425,000 in taxpayer money to the California-based nonprofit Playworks since 2011 to teach kids games at a handful of schools.

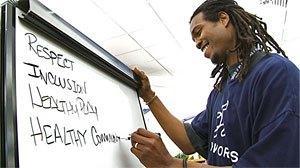

“We’re not teaching them how to play — we’re teaching them how to play respectfully,” said Playworks New York program manager Tashan Kilkenny, 25, known by kids as “Coach K.”

Under Playworks’ schoolyard rules, no child is “out” — they are merely “unsuccessful.” And to keep an “unsuccessful” kid involved, coaches will have him or her do a few jumping jacks or take on another role, such as “cheerleader.”

In a game of tag, a child isn’t tagged — but gently tickled on the shoulder.

Schoolyard conflicts? They’re settled with a round of rock, paper, scissors.

Five elementary schools — PS 2 in Chinatown, PS 198 on the Upper East Side, PS 9 in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn, PS 11 in Clinton Hill, Brooklyn, and PS 133 in Park Slope, Brooklyn — maintain full-time “recess coaches” employed by Playworks.

And in a pilot program launched last month, four elementary schools — PS 3 and PS 23 in Brooklyn and PS 44 and PS 83 in The Bronx — will share a single recess coach, with each school getting them one week a month. The coach not only supervises recess but trains junior coaches, runs parent-teacher sport nights and goes into three classrooms per day to teach new games.

The dozen “junior coaches” per school are selected from the ranks of fourth- and fifth-graders. They undergo leadership training and are called upon to settle spats, organize games and collect play equipment.

The primary aim is to get all children playing together, regardless of cliques. “We try and make everything as inclusive as possible,” said Kim McCall, executive director of Playworks in New York and New Jersey.

On Friday morning, at PS 9, coach Marquis Bethel, 25, watched over about 200 third-, fourth- and fifth-graders playing at exercise stations set up for four square, Switch (a game invented by Playworks), “one-shot basketball,” “three-line football,” a performing-arts stage, soccer and hula hoops.

Games aren’t compulsory. One girl read a book alone against a fence, while another section of the playground was dedicated to kids doing handstands and flips.

Before the program was introduced, PS 9 had segregated its playground into boys and girls sections over concerns about bullying and safety, Kilkenny said. When Playworks arrived four years ago, “they didn’t really know how to play,” said Kilkenny, explaining that kids knew the rules of basketball but didn’t know how to share a court.

Bethel — who is treated like a rock star by students desperate for a high-five from him — says that if he sees kids being excluded, he will call them over to “come hang with coach” and they will together join a team game.

Playworks says it aims to ensure kids have fun, stay active, fight obesity, reduce bullying and keep focused when back in the classroom. Unsurprisingly, the Playworks program was developed in Berkeley, Calif. It’s now in 900 schools nationally.

Not all experts are sold on the fun police, with some saying adults constantly managing playtime can impede a child’s creative and emotional development. “Children need some sort of unorganized and unsupervised playtime, specifically because it stokes their imagination and allows them to create imaginary worlds,” said Erik P. Hoel, a Ph.D. candidate in neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin.

A child’s ability to create imaginary worlds — such as giving a doll its own back story or inhabiting a fantasy universe — can be an indicator of future creativity and intelligence, Hoel said. “If you go your whole life with imaginary life being given to you instead of you creating your own, there’s kind of a learned helplessness in terms of creativity,” Hoel told The Post.

Plus, there are social benefits to kid-led playtime. “It allows them to self-organize and deal with common group dynamics that go along with being human . . . There’s not always going to be a teacher around,” Hoel said.

Playworks puts full-time coaches only at schools in low-income areas. The programs are half-funded by the DOE, with the other half coming from the nonprofit’s donors. With a lack of private funding, about a dozen city public schools are on a waiting list to get a Playworks’ recess coach.

DCG