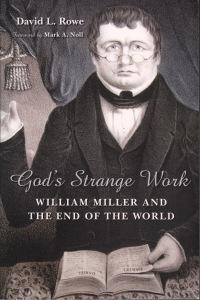

It’s a common name. You might know one yourself: William Miller. Indeed, for many years of my own life I borrowed that surname from my stepfather before returning to my birthright after seminary. But the ordinariness of the name alone doesn’t explain it. Joseph Smith, a fellow creator of a new religion, also bore an innocuous name, and he was a Junior. While many people might have trouble placing William Miller among religious founders, they would likely know of Seventh-Day Adventism, a religion that sprang from the root of his teaching. During his lifetime the preferred title was Millerite, but Adventist also worked. David L. Rowe presents a sympathetic, but not hagiographic account of this somewhat remarkable life in God’s Strange Work: William Miller and the End of the World. For Miller, you see, predicted the year Jesus would return.

It’s a common name. You might know one yourself: William Miller. Indeed, for many years of my own life I borrowed that surname from my stepfather before returning to my birthright after seminary. But the ordinariness of the name alone doesn’t explain it. Joseph Smith, a fellow creator of a new religion, also bore an innocuous name, and he was a Junior. While many people might have trouble placing William Miller among religious founders, they would likely know of Seventh-Day Adventism, a religion that sprang from the root of his teaching. During his lifetime the preferred title was Millerite, but Adventist also worked. David L. Rowe presents a sympathetic, but not hagiographic account of this somewhat remarkable life in God’s Strange Work: William Miller and the End of the World. For Miller, you see, predicted the year Jesus would return.

A self-taught farmer, Miller became convinced that the Bible indicated 1843 would be the end. This idea was based on calculations derived from cryptic books such as Daniel and considering their days to be years. A touch of math and before you know it, it’s all gonna burn. During the intense period known as the Second Great Awakening upstate New York was perhaps the most religiously creative place on the planet. New ideas bumped into each other and, as if the bounds of Christianity were too constraining, flew out into new forms of belief. People grew convinced that the world might indeed end in 1843. When it didn’t, they called it the Great Disappointment and carried on. Adventism is still with us today.

Rowe also makes the point that for being such an obscure individual, Miller influenced the great religious movements that would give us modern day Fundamentalism as well as Jehovah’s Witnesses. These groups trace their spiritual ancestry to the convictions of a not-so-simple farmer who could fill an auditorium with his plain speaking and clear exposition of the scriptures. He devised his end times scenario with the use of only a Bible and concordance. No seminary or advanced theological reading was necessary. Millerites did not reach the numbers of Latter-Day Saints. They were disowned by the Baptist Church that gave them birth. They got the date of the end of the world wrong. Yet they persisted. It is a curious story with a long afterlife that still helps elect extremist presidents to this day. William Miller, ever unassuming, managed to change the very world that he was certain would end even before the midpoint of the nineteenth century.