To preface this post, you should know that I am total conspiracy theorist. In most cases, it is not that I necessarily believe there is an uncovered hidden truth, I just simply like the mystery and uncertainty behind historical events – especially those related to sports. The Knicks winning the 1985 lottery (and Patrick Ewing). Michael Jordan’s “retirement” from the NBA and alleged gambling addiction. The Soviets winning the 1972 Olympic gold medal in basketball. The 1988 Wayne Gretzy trade (and later, his wife’s gambling ring). Tonya Harding, Mike Danton, and Pete Rose. Danny Almonte and the 2001 Little League World Series. The UNLV and SMU scandals. And, of course, the greatest sports conspiracy out there – the 1919 Chicago Black Sox.

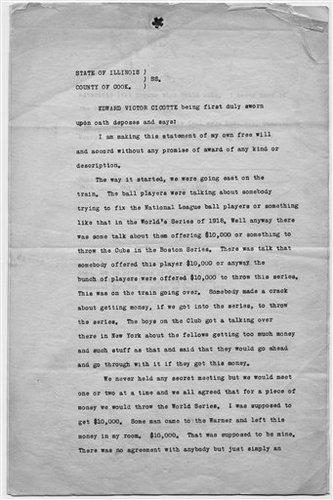

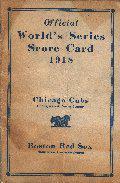

To preface this post, you should know that I am total conspiracy theorist. In most cases, it is not that I necessarily believe there is an uncovered hidden truth, I just simply like the mystery and uncertainty behind historical events – especially those related to sports. The Knicks winning the 1985 lottery (and Patrick Ewing). Michael Jordan’s “retirement” from the NBA and alleged gambling addiction. The Soviets winning the 1972 Olympic gold medal in basketball. The 1988 Wayne Gretzy trade (and later, his wife’s gambling ring). Tonya Harding, Mike Danton, and Pete Rose. Danny Almonte and the 2001 Little League World Series. The UNLV and SMU scandals. And, of course, the greatest sports conspiracy out there – the 1919 Chicago Black Sox.  The Black Sox, immortalized by Eliot Asinof in Eight Men Out, threw the 1919 World Series after being paid off by professional gamblers. Recently, the Chicago History Museum released a 1920 deposition by Eddie “Knuckles” Cicotte, a pitcher for the Black Sox and one of the eight players permanently banned from baseball. The deposition scandalously suggests that the Black Sox were inspired to fix the World Series by the Chicago Cubs – who had done it one year earlier. Specifically, Cicotte stated that “the boys on the club” discussed how members of the Cubs were offered $10,000 to throw the 1918 World Series against the Red Sox, which they wound up losing 4-2 in a tight match-up. He said that during a train ride from Chicago to the East Coast, “the ball players were talking about somebody trying to fix the National League ball players.” After explaining how the Cubs were paid to lose to Boston, “[s]omebody made a crack about getting money, if we got into the Series, to throw the Series." He does not provide many details – failing to mention names or strategy – but the implications are so intriguing.

The Black Sox, immortalized by Eliot Asinof in Eight Men Out, threw the 1919 World Series after being paid off by professional gamblers. Recently, the Chicago History Museum released a 1920 deposition by Eddie “Knuckles” Cicotte, a pitcher for the Black Sox and one of the eight players permanently banned from baseball. The deposition scandalously suggests that the Black Sox were inspired to fix the World Series by the Chicago Cubs – who had done it one year earlier. Specifically, Cicotte stated that “the boys on the club” discussed how members of the Cubs were offered $10,000 to throw the 1918 World Series against the Red Sox, which they wound up losing 4-2 in a tight match-up. He said that during a train ride from Chicago to the East Coast, “the ball players were talking about somebody trying to fix the National League ball players.” After explaining how the Cubs were paid to lose to Boston, “[s]omebody made a crack about getting money, if we got into the Series, to throw the Series." He does not provide many details – failing to mention names or strategy – but the implications are so intriguing. I have always naively looked at the Black Sox as an anomaly; one particularly greedy baseball team that, in the shadow of their evil owner, took matters into their own hands and put money ahead of the game. But the deposition blows that theory out of the water. If true, it implies that this sort of scheming and game fixing was almost commonplace. Especially in Chi-town. This was a time before baseball players were treated like celebrities and paid like movie stars. Before free agency or a union. Players constantly griped about their low salaries and, more vehemently, about their greedy owners. It makes the possibility of a fix not only plausible, but probable.

Sean Deveney, a reporter for The Sporting News and author of The Original Curse, asserts that the Cubs “had the incentive to do something like that” and that “there were definitely some suspicious plays” in the 1918 World Series. At that time, the Cubs and Red Sox were frustrated with their owners because they would not agree to equitably share profits from the Series. It was so tense that, before the start of one game in Boston, both teams refused to take the field until they were paid upfront. The owners would not comply, and the players were aware that they would be criticized for not playing, especially in the midst of World War I. So maybe, just maybe, they took advantage of the little control they still had and threw the 1918 World Series. While there is no glaring or conclusive data, let’s act like Nancy Drew and investigate:

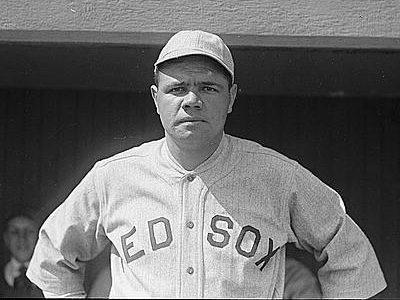

Sean Deveney, a reporter for The Sporting News and author of The Original Curse, asserts that the Cubs “had the incentive to do something like that” and that “there were definitely some suspicious plays” in the 1918 World Series. At that time, the Cubs and Red Sox were frustrated with their owners because they would not agree to equitably share profits from the Series. It was so tense that, before the start of one game in Boston, both teams refused to take the field until they were paid upfront. The owners would not comply, and the players were aware that they would be criticized for not playing, especially in the midst of World War I. So maybe, just maybe, they took advantage of the little control they still had and threw the 1918 World Series. While there is no glaring or conclusive data, let’s act like Nancy Drew and investigate:Game 1 (9/5/1918 in Chicago): Babe Ruth dominated and pitched a shutout. In the fourth inning, some dude named Stuffy McInnis had the game’s only RBI, which he hit it off some other dude named Hippo Vaughn. The battle of Stuffy vs, Hippo was the most interesting thing that happened during Game 1, unless you count “The Star Spangled Banner,” which was sung for the first time ever at a sporting event. In fact, it wasn’t even declared our national anthem until 1931. Red Sox 1, Cubs 0.

Game 2 (9/6/1918 in Chicago): This game was equally uneventful. The Cubs carried a shutout into the ninth behind Lefty Tyler’s strong pitching. He also had a two-run single, helping his own cause. Cubs 3, Red Sox 1.

Game 3 (9/7/1918 in Chicago): So this is when things get a little weird. The game remained in Chicago because of war-time restrictions on travel, and Red Sox pitcher Carl Mays was effective, but not dominant. He allowed seven hits and a lot of base runners, but the Red Sox led by one run going into the ninth. The game ended, however, when the Cubs’ Charlie Pick curiously attempted to score on a passed ball and got caught in a rundown between third and home. Red Sox 2, Cubs 1.

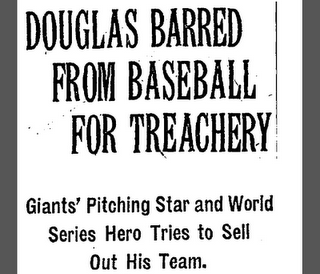

Game 4 (9/9/1918 in Boston): Okay, now we officially step into the land of crazy. Right fielder Max Flack was picked off twice in this game. In the fourth inning, as Babe Ruth came to the plate, Lefty Tyler noticed that Flack was playing really shallow and motioned for him to move back. Flack just stood there. Ruth then proceeded to smash a triple over his head, scoring two runs. He remains the only starting pitcher in World Series history to bat anything other than ninth. After the Cubs tied the game in the eighth, the Red Sox went on to win in a wild bottom half of the inning. First, there was a passed ball by catcher Bill Killefer, allowing runners to advance. Then, relief pitcher Phil Douglas fielded a soft grounder and hurled it over first base, which allowed the winning run to score. Have no fear, we will come back to Mr. Douglas later. Red Sox 3, Cubs 2. Game 5 (9/10/1918 in Boston): This one was pretty boring. My boy Hippo finally won a game, throwing a five-hit shutout. Cubs 3, Red Sox 0.

Game 4 (9/9/1918 in Boston): Okay, now we officially step into the land of crazy. Right fielder Max Flack was picked off twice in this game. In the fourth inning, as Babe Ruth came to the plate, Lefty Tyler noticed that Flack was playing really shallow and motioned for him to move back. Flack just stood there. Ruth then proceeded to smash a triple over his head, scoring two runs. He remains the only starting pitcher in World Series history to bat anything other than ninth. After the Cubs tied the game in the eighth, the Red Sox went on to win in a wild bottom half of the inning. First, there was a passed ball by catcher Bill Killefer, allowing runners to advance. Then, relief pitcher Phil Douglas fielded a soft grounder and hurled it over first base, which allowed the winning run to score. Have no fear, we will come back to Mr. Douglas later. Red Sox 3, Cubs 2. Game 5 (9/10/1918 in Boston): This one was pretty boring. My boy Hippo finally won a game, throwing a five-hit shutout. Cubs 3, Red Sox 0.Game 6 (9/11/1918 in Boston): After his stellar Game 4 performance, Max Flack decided to step it up a notch. In the third, he somehow turned an easy fly ball into an error, allowing two runs to score. Those two runs were all Boston needed, sealing their World Series title. Red Sox 2, Cubs 1.

So there we have it. Please note that the Cubs’ team ERA for the World Series was a ridiculous 1.04. Either the Boston hitters completely sucked (um, they had Babe Ruth) or the Chicago pitchers weren’t in on the fix. That said, there were undoubtedly some fishy things that happened. Only 19 runs were scored throughout the entire Series. All six games were incredibly close. But because they were so close, it makes the possibility of a fix more likely. Sean Deveney concluded that while “it didn’t take much to throw a game . . . Baseball didn’t want to investigate. They wanted to make it all about the Black Sox and say, ‘Okay, gambling’s gone.’” But, as Pete Rose would later make clear, gambling was never truly gone. It never will be.

So there we have it. Please note that the Cubs’ team ERA for the World Series was a ridiculous 1.04. Either the Boston hitters completely sucked (um, they had Babe Ruth) or the Chicago pitchers weren’t in on the fix. That said, there were undoubtedly some fishy things that happened. Only 19 runs were scored throughout the entire Series. All six games were incredibly close. But because they were so close, it makes the possibility of a fix more likely. Sean Deveney concluded that while “it didn’t take much to throw a game . . . Baseball didn’t want to investigate. They wanted to make it all about the Black Sox and say, ‘Okay, gambling’s gone.’” But, as Pete Rose would later make clear, gambling was never truly gone. It never will be.  And doubts linger. For example, Pitcher Claude Hendrix was accused of fixing a game in 1920, but he immediately retired and was never officially suspended. On the other hand, Phil Douglas (of Game 4 infamy) was accused in August 1922 of what the New York Times called “treachery” and was banned for life from baseball. Specifically, he wrote a letter and proposed that a rival team pay him to abruptly quit the Giants, who he played for at the time, and “go fishing.” He claimed in the letter that the Giants “can’t win [the Pennant] without me.” Besides being a total prick, it is even easier to hate him knowing that he may have gifted a World Series to the Boston Red Sox. A victory they would not taste again until 2004.

And doubts linger. For example, Pitcher Claude Hendrix was accused of fixing a game in 1920, but he immediately retired and was never officially suspended. On the other hand, Phil Douglas (of Game 4 infamy) was accused in August 1922 of what the New York Times called “treachery” and was banned for life from baseball. Specifically, he wrote a letter and proposed that a rival team pay him to abruptly quit the Giants, who he played for at the time, and “go fishing.” He claimed in the letter that the Giants “can’t win [the Pennant] without me.” Besides being a total prick, it is even easier to hate him knowing that he may have gifted a World Series to the Boston Red Sox. A victory they would not taste again until 2004.  What do I take from all of this? A few things: 1) Chicago is a city of cheaters. If you are from there, visited there, lived there, or ever found it on a map, you have probably cheated at something or on someone. Chicago = dirty bastards. I’d bet Sammy Sosa’s corked bat on it. 2) The Red Sox did not in any way deserve to win the World Series (ever), but especially in 1918 – which would have extended our taunting of them for an additional two years. You took that away from Yankee fans everywhere and such “treachery” can never be forgiven. 3) It is an extremely wonderful thing that baseball players now get paid an obscene amount of money. Whew, no more cheating. We now only have to worry about steroids, human growth hormone, forged birth certificates, tipped-off PED testing, bribery for prospects in Latin America, and humidored balls. God, I love a good sports scandal.

What do I take from all of this? A few things: 1) Chicago is a city of cheaters. If you are from there, visited there, lived there, or ever found it on a map, you have probably cheated at something or on someone. Chicago = dirty bastards. I’d bet Sammy Sosa’s corked bat on it. 2) The Red Sox did not in any way deserve to win the World Series (ever), but especially in 1918 – which would have extended our taunting of them for an additional two years. You took that away from Yankee fans everywhere and such “treachery” can never be forgiven. 3) It is an extremely wonderful thing that baseball players now get paid an obscene amount of money. Whew, no more cheating. We now only have to worry about steroids, human growth hormone, forged birth certificates, tipped-off PED testing, bribery for prospects in Latin America, and humidored balls. God, I love a good sports scandal.