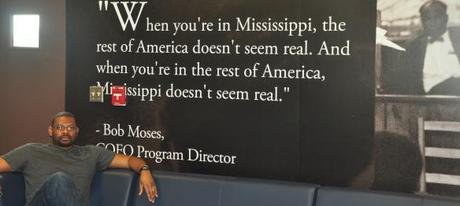

Carolyn Dupont realizes that all southern states are not created equal. Life in the Jim Crow South was hard everywhere, but Mississippi was frighteningly unique. As Bob Moses likes to say, “When you’re in Mississippi, the rest of America doesn’t seem real. And when you’re in the rest of America, Mississippi doesn’t seem real.”

Across the South, white evangelicals were serious about defending segregation, but there was always a veneer of moderate opinion to counterbalance the bigotry. In Mississippi, only a handful of white people stood against segregation, and they paid dearly for that stand.

But Carolyn Dupont isn’t thumbing her nose at the Magnolia State, she honestly wonders what folks had to do to the religion of Jesus to justify such a damaging institution. AGB

White Supremacy, Evangelicals, and Mississippi’s 1964 Freedom Summer

Fifty years ago this month, Americans gazed with horror as Mississippi morphed into an eerie caricature of itself. The three civil rights workers famously killed in Neshoba County in June 1964 constituted but one episode in a larger orgy of white-supremacist violence. Four other civil rights volunteers lost their lives, while thugs beat others, bombed movement headquarters, shot into the windows of activists’ homes, and burned 54 black churches by summer’s end. Even for those without personal memories of these events, Mississippi’s “Long, Hot Summer” lies branded in the national consciousness both as a moment of shame and a catalyst to action.

Yet rarely do recollections of this high civil rights drama consider the religious backdrop for these grisly events. Paradoxically, it would seem, Mississippi boasted among the highest degrees of religious adherence in the nation; more than 60 percent of the state’s whites identified as either Southern Baptist or Methodist, and membership in other denominations pushed rates of observance over 90 percent. Importantly, by the summer of 1964, the state’s white religious bodies had repeatedly and decisively rejected the quest for black equality. While national representatives of the Southern Baptist Convention, the Methodist Church, and the Southern Presbyterian Church all endorsed the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Educationruling on school desegregation, Mississippi spokesmen for these groups denied its applicability to their state. While black Americans waged a death-defying struggle for their full humanity, leading religious figures in Mississippi lent their pens to the cause of white supremacy and white congregations affirmed the virtues of segregation. When 28 young Methodist ministers authored a manifesto suggesting that “our Lord Jesus Christ… permits no discrimination because of race, color, or creed,” their Mississippi coreligionists responded with swift and decisive censure. Perhaps most ingloriously, beginning in June 1963, white congregations in Jackson rejected black activists who came to Sunday worship. For the next nine months, the city’s once-serene Sabbaths turned tumultuous, as police with clubs, dogs, and wagons protected the white churches from “disturbances to divine worship.” This ordeal culminated on Easter Sunday 1964, when a downtown Methodist Church refused two bishops of its own denomination.

If by June of 1964 Mississippi’s white Christians had not adequately disavowed racial integration, a final opportunity arose when Southern Baptists from across the country streamed to Atlantic City, NJ for their annual convention — just weeks before the three civil rights workers disappeared. Progressives at this meeting offered up a statement that condemned segregation, endorsed civil rights activity, and urged support of the Civil Rights Bill then before Congress. Yet Baptist leaders from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama substituted a much watered-down version that excised all such endorsements and offered only the rather innocuous recommendation that “Christians and churches [act] under the direction of the Holy Spirit and in the spirit of our Lord Jesus Christ.” The Convention narrowly approved the eviscerated statement, relegating the progressive report to the trash heap. And even as Mississippi Baptists returned home to the summer’s escalating violence, they castigated the socially conscious arm of their denomination for its “liberalism” and its attention to the “distraction” of race relations, arguing that the “cause of Christianity is being undermined by leaders who are more interested in social reforms than the Gospel of Jesus Christ.”

Indeed, the religion woven so deeply into the fabric of southern society proved empty and impotent at this moment of stunning crisis. Speaking historically, little should surprise here. Devout Christians had sanctioned slavery’s ascension as the backbone of the American economy, rushed to champion the Confederacy, and later presided over the rise of Jim Crow. Yet, simply casting stones at a faith many find profoundly meaningful misses the point entirely and yields little in the way of helpful understanding. A far more useful approach will ask: What particular kind of Christianity enables the faithful to repeatedly enact such horrific costs from other human beings? To be sure, in America, a hyper-individualistic version of Christianity has often stripped the Gospel of all social implications, insisting that individual salvation provides the answers to all social ills. In the civil rights era, white evangelicals claimed that race relations would improve “one heart at a time,” citing an American-made faith that renders illegitimate any critique of the systems that enslaved and oppressed millions.

Indeed, many today who do not embrace evangelical religion yet display its legacy. Like Mississippi evangelicals who fiddled “Just as I Am” while their state burned, they prefer to believe that personal responsibility and individual effort alone determine every life path. Such worshipers of hyper-individualism ignore to the point of absurdity the larger structures that constrain our choices and shape our destinies. For them, America’s gross inequities — in education, housing, criminal justice, and employment — remain invisible. And like white supremacists at mid-century, they strive mightily to keep these systems intact.

Carolyn Dupont is the author of Mississippi Praying: Southern White Evangelicals and the Civil Rights Movement, 1945-1975 and Assistant Professor of History, Eastern Kentucky University.