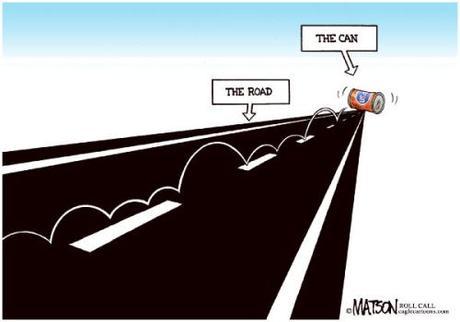

LA Times: California taxpayers have never paid more for public worker pensions, but it’s still not enough to cover the rising number of retirement checks written by the state’s largest pension plan. Even before the stock market’s recent fall, staffers at the California Public Employees’ Retirement System were worried about what they call “negative cash flows.”

The shortfalls — which totaled $5 billion last year — are created when contributions from taxpayers and public employees who are still working aren’t enough to cover monthly checks sent to retirees. To make up the difference, CalPERS must liquidate investments.

With more than $300 billion in investments, the nation’s largest public pension fund is in no danger of suddenly running out of cash. But even its staff acknowledges in a recent report that despite fast-rising contributions from taxpayers, the pension fund faces “a significant amount of risk.”

To reduce that financial risk, CalPERS has been working for months on a plan that could cause government pension funds across the country to rethink their investment strategies. The plan would increase payments from taxpayers even more in coming years with the goal of mitigating the severe financial pain that would happen with another recession and stock market crash.

Under the proposal, CalPERS would begin slowly moving more money into safer investments such as bonds, which aren’t usually subject to the severe losses that stocks face. Because the more conservative investments are expected to reduce CalPERS’ future financial returns, taxpayers would have to pick up even more of the cost of workers’ pensions.

Most public workers would be exempt from paying any more. Only those workers hired in 2013 or later would have to contribute more to their retirements under the plan.

The changes would begin moving CalPERS — which provides benefits to 1.7 million employees and retirees of the state, cities and other local governments — toward a strategy used by many corporate pension plans. For years, corporate plans have been reducing their risk by trimming the amount of stocks they hold. The plan is the result of CalPERS’ recognition that — even with significantly more contributions from taxpayers — an aggressive investment strategy can’t sustain the level of pensions promised to public workers. Instead, it could make the bill significantly worse.

At an Aug. 18 meeting, CalPERS staff members laid out their plan for the fund’s board, saying the changes would be made slowly and incrementally over the next several decades. That isn’t fast enough for Gov. Jerry Brown. A representative from the governor’s finance department addressed the CalPERS board, saying the administration wants to see financial risks reduced “sooner rather than later.” “We know another recession is coming,” said Eric Stern, a finance department analyst, “we just don’t know when.”

CalPERS lobbied for those more expensive pensions. In a brochure, the fund quoted its then-president, William Crist, saying the pension-boosting legislation was “a special opportunity to restore equity among CalPERS members without it costing a dime of additional taxpayer money.” That has turned out to be wishful thinking. Now, cities and other local governments are cutting back on street repairs and other services to pay escalating pension bills.

Chris McKenzie, executive director of the League of California Cities, said governments are in the midst of a six-year stretch in which CalPERS payments are expected to rise 50%. Some cities are now paying pension costs that are equal to as much as 40% of an employee’s salary, according to CalPERS documents. The cost is highest for police, fire and other public safety workers who often receive earlier and more generous retirements than other employees. In recent years, three California cities have declared bankruptcy, in part, because of the rising costs.

McKenzie said that despite the escalating pension bills, most cities are in favor of the plan by CalPERS staff. Many city finance officials believe that CalPERS’ investment portfolio is currently “too volatile,” he said. About 10% of cities don’t support the plan, McKenzie said. “Some said they simply can’t afford it,” he added.

Representatives from two public employee labor unions speaking at the Aug. 18 meeting said they generally supported the plan. The plan must be approved by CalPERS’ board, which is scheduled to discuss it again in October.

Last year, governments sent CalPERS $8.8 billion in taxpayer money, while employees contributed an additional $3.8 billion, according to financial statements for CalPERS’ primary pension fund. Those combined contributions fell $5 billion short of the $17.8 billion paid to retirees.

At the heart of the plan is the gradual reduction in what CalPERS expects to earn from its investments. Currently, CalPERS assumes its average annual investment return will be 7.5% — an estimate that has long been criticized as being overly optimistic. After several years of double-digit returns, the giant pension fund’s investments earned just 2.4% in 2014, according to preliminary numbers released in July. Under the new plan, as CalPERS moved more money to bonds and other more conservative investments to reduce risk, the 7.5% rate would gradually be reduced.

CalPERS is still recovering from the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009, when it suffered a 24% loss on its investments. Today its $300 billion in investments is estimated to be only about 75% of what it already owes to employees and retirees. A market downturn would create an even deeper hole.

In presentations, CalPERS told city finance officials that if its investments drop below 50% of the amount owed for pensions, even with significant additional increases from taxpayers, catching up becomes nearly impossible.

See also:

- Shocker, not: No high-deductible CalPERS medical plan in California budget

- Shocker, not: Despite strong returns, California pension funds’ fiscal hole got deeper

DCG