Sacramento Bee: Lindsay Rains has worked steadily for the last few years as an environmental scientist at the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s offices in downtown Sacramento.

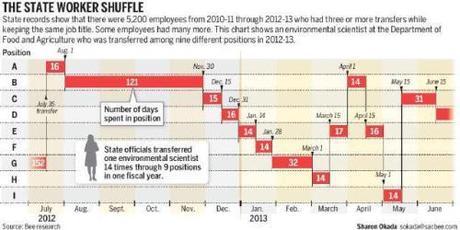

According to state personnel records for 2012 and 2013, however, she transferred 14 times through nine positions in one fiscal year. Her title never changed, but the serial numbers the state uses to identify her position changed repeatedly.

The maneuver is one state departments have used to pad their budgets with millions of tax dollars earmarked for employee salaries. By law, they are supposed to lose the money when a position goes unfilled for six months. Instead, they have simply altered the identifying numbers to make it appear that a job was filled with a transferred employee, thus avoiding a cut to their budgets.

The unspent salary money can then be used to cover other operating costs, such as leave balances, office rent, new equipment or employee raises.

The transfers don’t promote the employees, who may not even know about the numerical changes. Officials at the Department of Food and Agriculture declined to respond to inquiries.

Thousands of personnel transfers reviewed by The Sacramento Bee show similar patterns throughout state government.

Mike Genest, former Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s finance director, looked through some of the state transfer data and called the patterns he saw “smoking-gun stuff” that strongly suggests departments have gamed the law.

“If you think about it, people had to scheme to do this,” Genest said. Now outside government, he sees the practice as a problem, but he acknowledged he allowed it when he worked as a deputy director for the Department of Social Services and the Department of Health Services in the 1990s.

Genest said he tried to stamp it out during his tenure as finance director: “It constitutes a conspiracy, and it’s going on throughout state government,” he said.

The transfer data, obtained by The Bee through a Public Records Act request, covered more than 17,500 positions at about 110 departments.

Roughly 5,200 state employees shuttled between three or more job positions without changing departments or job titles, according to state Controller’s Office records for the last three fiscal years.

The transfers sometimes occurred within days of each other. Many employees, such as Rains, changed position numbers every few months. Other examples captured in the controller’s data include:

• A Department of General Services executive, Ricardo Martinez, was transferred 11 times between three positions over the course of 18 months.

• An analyst for the Department of Child Supportive Services, Tristina Thiel, moved seven times in a year, with one transfer lasting just two days.

• Daniel Kieselhorst, a Department of State Hospitals printing press operator, was moved back and forth between the same two positions 15 times in three years.

Illegally shuffled employees aren’t breaking the law, and the workers either declined comment or could not be reached. They may not know they’ve been used for an illegitimate transaction because their pay, duties and job titles remain the same.

And some transfers in the data appeared to be legitimate, such as when an employee moved between programs in the same agency.

The Bee sent employee transaction information to several departments that the data suggested may have engaged in suspicious transfers: the Department of State Hospitals, Department of Social Services, Department of Food and Agriculture, Department of General Services and Caltrans. Some did not return multiple phone messages and emails. Others said that they needed time to digest the numbers or referred The Bee to other Brown administration officials. None agreed to interviews.

Bee reporters also met two weeks ago with Lynda Gledhill, press secretary for the Government Operations Agency, and H.D. Palmer, a deputy director at the state Department of Finance, to show the Brown administration several examples of dubious employee transfers.

Palmer acknowledged the problem. “You can’t order a la carte,” he said. “You can’t pick and choose what law you’re going to follow.”

On May 16, responding to The Bee’s findings, the administration issued a memo reminding personnel officers about the job-vacancy law’s ban on such transfers. The memo also announced that finance officials are launching “a targeted audit” that will look for illegal transactions.

On Friday, Marybel Batjer, secretary of the Government Operations Agency, sent a letter to key lawmakers advising them that officials had “recently learned” that departments had taken “actions inconsistent with” the law. In addition to the audit, she said finance officials will also assess the law, noting that its effectiveness has long been questioned.

“However, while the law remains in effect, the Administration is fully committed to compliance,” she wrote.

‘Byzantine solution’

How much could the state have used for other purposes had the positions been abolished? It’s impossible to calculate an exact number, since some of the transactions were legitimate. At a minimum, though, the positions with three or more transfers in a given year had average total pay of more than $80 million.

Jon Coupal of the Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association said the transfers are another example of misplaced bureaucratic priorities. “If you defaulted to the private sector, you would hire people based on need,” he said, calling the state’s six-month law a “bizarre and byzantine solution.”

Departments manipulate the transfer system for several reasons, those familiar with the practice say. “There’s bureaucratic pressure to do this from midmanagers busting their asses to not lose the positions. They want to keep that money in the bank,” said a former high-level administration official who asked not to be named because he still interacts with state government.

Some state positions are difficult to fill within six months. The state’s hiring process can take much longer to process an applicant. Some jobs require special skill sets. The state’s pay isn’t competitive for many classifications, such as lawyers and scientists, which slows hiring.

Department administrators have long complained that they do not receive enough money from the Legislature for their operations, said Nick Schroeder, a state government workforce expert in the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office, “so a lot of departments are probably leaving positions open to pay for those costs.”

“To the extent that departments are underfunded for their basic operations, (it) creates pressure to hold positions vacant in order to use the funding for those positions to support their operations,” said Tim Gage, former Democratic Gov. Gray Davis’ finance director. “That said, the only way that the Legislature and the governor can manage the budget is to maintain control over the number of authorized positions.”

For many years, the state assumed that departments wouldn’t fill all of their jobs and automatically cut personnel budget requests. A department that said it needed 100 employees, for example, might be funded for just 95.

That policy, Genest said, created pressure for departments to inflate their personnel estimates and load up extra funded vacancies as a hedge against the inevitable funding cut. The state ended the so-called “salary savings” policy two years ago, hoping to gain a more realistic picture of staffing costs. That move wiped out nearly 12,000 vacant positions that departments were carrying on the books.

Genest described a government process that penalizes thrifty departments, since future budgets are based on current spending. Manipulating employee transactions was expected when he worked for the social services and health services departments, he said, and managers became upset if they lost money because a vacant position was swept out.

“It almost forces people to disobey the law,” he said. “I know. I played the game myself.”

The law relies on departments to be honest. There’s no watchdog that checks every transaction to determine whether employers are manufacturing personnel moves to keep vacant slots and the tax dollars budgeted for them.

Doing so would require diving into thousands of personnel records each year and matching them against tens of thousands of employee transfers executed by the state’s 150 or so agencies, departments, commissions and boards.

State officials had never collated data that might flag suspicious transfer trends statewide until The Bee requested employee transaction reports. The Controller’s Office had to write a special program to cull the data.

Few vacancies abolished

California lawmakers and bureaucrats have sparred over vacant positions for years.

A vacancy law enacted in 1983 sought to control a growing number of vacancies carried on departments’ books. The law originally axed slots that were empty for the last nine months of the July-through-June fiscal year. Departments could retain the positions if a hiring freeze prevented filling them. If lawmakers failed to enact a budget on time – a once-common occurrence that froze hiring – or if the position was truly hard to fill, employers could ask the Finance Department to re-establish the vacancy and the money tied to it.

The fiscal-year confines of the law meant that jobs that went vacant after October could go unfilled well over 12 months, and departments could easily manipulate vacancies to retain them. As a result, few vacant positions were abolished. For fiscal 1999-00, for example, the controller eliminated 94 of 227,000 state positions.

Lawmakers in 2000 shortened the time a job could remain vacant to six months in a fiscal year, but that still allowed positions first vacant after Jan. 1 to stay on a department’s books for nearly a year.

Two years later, a state audit noted that 536 vacant positions had been abolished the first year under the tighter law. But State Auditor Elaine Howle reported that nearly 90 percent of the employee transfers in five departments auditors closely scrutinized were intended to “avoid the abolishment of vacant positions.” One of the departments, the audit found, devoted 46 weeks of staff time to monitoring vacancies and manipulating transfers.

“(T)he law’s effectiveness,” Howle summed up in a 2002 letter to lawmakers, “is hindered by departments’ efforts to preserve positions.”

Over the next five years, the Legislature added several exemptions to the vacancy law, including jobs held open for employees on military or medical leave, or positions vital to public health and safety. The vacancy trigger was tweaked to abolish positions even if the six months straddled two fiscal years. But perhaps the most significant was this caution, added in 2002: “Departments shall not execute any personnel transactions for the purpose of circumventing the provisions of this (law).”

The state Legislative Analyst’s Office concluded in 2008 that so little savings were realized from the law that it should be eliminated.

“We believe that the wide variety of exemptions in the law, as well as an undetermined amount of departmental actions to evade its requirements, are the likely reasons for so few positions being eliminated,” it said.

DCG

Read more here: http://www.sacbee.com/2014/05/30/6446017/california-state-departmeplay.html#storylink=cpy