Monkey see, monkey do. We may not be monkeys, but we frequently ape others, mirroring their posture, behavior mood. When we act angrily, others respond with anger. When we act kindly, others respond in kind.

Invisibilia’s latest episode looks at what we can do when we flip this script, and respond in an unexpected way with non-complimentary behavior. Here I’ll discuss some of science mentioned in the show and extend it into the wonderful world of mirroring to teach you a very important life skill–how to spot the coolest dude in the room.

So what is non-complimentary behavior?

See example 1 of armed robbery, wine, and non-complimentary behavior from the show illustrated with puppets:

And example 2, eerily similar story of armed robbery, wine, and non-complimentary behavior that I clipped out a recent episode of The Organist (but no puppets, sorry!):

The Invisibilia episode continues with a story from Denmark of fighting against the Islamic radicalization with forgiveness and kindness. Many young radicalized Danes who idealistically left to fight in Syria but got in over their heads, and when they realize that their home-country is flipping the script, and welcoming and reintegrating the returning soldiers as opposed to punishing them, many return.

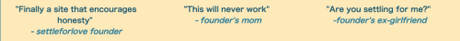

Finally, it ends with an interview of founder of Settle For Love a dating site that encourages users to post not only their flattering photos and most enticing biographies but also their imperfections. It aims to allow for more honest dating and more up-front screening of potential mates on the logic that by being vulnerable, others will respond in kind. Simple complementary behavior right.

The Interpersonal Complementary Hypothesis

In NPR’s accompanying health shots blog clinical science professor Chris Hopwood shows some more examples of complementary and non-complementary behavior–and explains an extra layer of the theory. According to the interpersonal complementary hypothesis, there are two types of reactions to behaviors:

- Complementary – responding in kind to another’s actions, as we previously discussed

- Reciprocal – when a person acts dominant others will respond submissively and vice versa.

Hopwood explains how complementary behavior can negatively affect our relationships. While complementary responses are natural, they can create a kind of a feedback loop that can only be broken through the potentially awkward and difficult act of acting in a non-complementary way. Sometimes the only way to get out of a fight is to act kindly to someone who is being a jerk. However, Hopwood also warns that too much non-complementary behavior can be problematic: if we always give too much warmth we can be taken advantage of, or if we respond to dominance with dominance we may end up in a fight.

Mirroring

In social psychology, mirroring refers to the unconscious way we mimic others gestures, speech, or attitudes. Mirroring takes place all the time and usually we don’t notice when we mirror others, or others mirror us, but if you pay attention, you can catch it in action.

For example, I have a bad habit of awkwardly hold my left bicep with my right hand when I get nervous—it’s weird I know, don’t judge me! This posture is basically unique to me; I don’t know if I’ve ever seen someone else do it spontaneously. Often I don’t even realize I’m doing it myself… until the person I’m talking to starts to do it as well, because they are mirroring me!

Mirroring and Social Status – (How to figure out who’s the coolest guy in the room)

If you notice someone mirroring you, take it as a compliment. We tend to mirror others more when we want to be liked by them. Also, we tend to imitate those of higher social status more, and people belonging to stigmatized groups less. So by observing who’s mirroring who, you can figure out where people place themselves and each other in their unconscious hierarchies, and figure out who has the most status in the room.

From the other perspective, people being imitated tend to favor people who mirror them over people who don’t. This finding has even extended to the likeability of computer-controlled avatars in virtual reality.

Conclusions

It has been proposed that mirroring may derive at some level from the actions of mirror neurons—neurons that fire both when observing and doing an action—but because of technically limitations direct evidence from humans is lacking. Regardless of their neurobiological mechanism, on many levels imitation both unconscious and conscious seems crucially important to humanity—before we understand language we imitate the sounds of speech and have an ability that’s rare in the animal kingdom to learn not just from doing but also from observing.

Because it is so universal and instinctual, complementary behavior is likely similarly important. However, as shown by the clips from Invisibilia and The Organist, sometimes if we work against this instinct and do something that at first doesn’t feel quite right, it can end up being the perfect response.