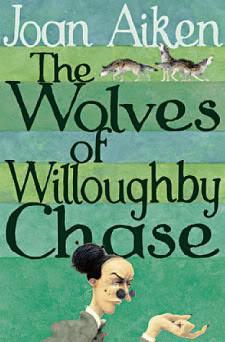

The Wolves of Willoughby Chase; Joan Aiken

Set in an alternate version of history in which James II was not deposed in the Glorious Revolution, The Wolves of Willoughby Chase imagines an England roamed by wolves that have migrated through mainland Europe from Russia through a pre-Eurotunnel undersea excavation. This is not as outlandish as it may seem; a tunnel under the English Channel was first proposed in 1802, and in the 1830s geo- and hydrographical surveys were performed with a view to making the proposal a reality.

The book is the first in a series of 12 novels alternatively called the Wolves Chronicles and James III Series. It was adapted to film in 1989. My copy, a Red Fox edition published in 1992, soft spined and fluffy from having been read too often in a bath not been picked up for at least 15 years, so I’ve only a vague memory of it. No details of the plot remain, only the tone has stayed with me. Joan Aiken is a beloved author for emerging and middle readers and a doyenne of juvenile fiction. It is a scandal that I have ignored her for so long.

The story begins with a treacherous train journey north from London for Sylvia, our orphaned protagonist, who is to join her cousin Bonnie at the family seat, Willoughby Chase, a grand Medieval hall that sits at the center of a wold occupied by half-starved wolves. They are to be educated by the new governess Miss Slighcarp who will be acting in loco parentis while patriarch Sir Willoughby and his wife Lady Green are away traveling. She is given complete control of the estate.

Miss Slighcarp instantly shows her colours. She dismisses most of the estates large staff and starts wearing Lady Green’s expensive gowns. She orders the girls must clean their own bedrooms – a fate worse than death to the average ten-year-old – and eat only plain food. She locks Bonnie in a cupboard, and, with the help of the mysterious Mr Grimshaw, begins a systematic assault on the Willoughby fortune.

To call a the characters of a novel tightly archetypal would generally be to disparage the text. Aiken’s female characters are just that: primary antagonist Miss Slighcarp (it is she pictured in the cover art above) could be swapped out for potions teacher Miss Hardbroom in Jill Murphy’s The Worst Witch series. She’s a callous and conniving maiden aunt, gaunt and balding under her wig, who beats servants with a marble hairbrush and demands respect while doing nothing to deserve it. She is the wicked stepmother archetype incarnate; cruel, ruthless, and entirely self-serving.

By contrast, Pattern embodies another archetype. She’s a fairy godmother, a caregiver and guiding hand

You can get away with resorting to caricature when your prose is as fine as Aiken’s. The writing is sumptuous and flowing. It is perfectly pitched for the emerging lone reader, but with a breadth of language - pages 14/15 alone provides chatelaine, oubliette, commodious and portico – to challenge and enrich the young reader’s vocabulary. Contextual clues often define these unexpected words, as when Miss Slighcarp wishes her belongings to be moved:

“You Sir! Do not stand there smirking and dawdling, but see that my valises are carried at once to my apartments, and that my maid is immediately in attendance to help me.”

The average 21st century tween cannot be expected to have come across the word ‘valise’ before but can probably surmise that it is an item of luggage, and probably a specialised one*.

I’ve perhaps gone on a bit too long about long words, but the trick Aiken has managed to pull off here is not an easy one. The language is not so complex to be off-putting, but nor does it underestimate the reader.

An overarching theme of the novel is to nether take for granted what you have, nor wish for better. Sylvia finds herself amid the opulence of the Chase after living in a small flat in London. Where once she had a dress made from a curtain and

*Miss Slighcarp arrives with a dressing case and nine walrus hide portmanteaux as well as the valise. She does not travel light.