Several years ago I picked up Charles Mann’s 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. While I don’t remember many specifics, I do recall enjoying it quite a bit. One idea floated in the book has stuck with me since: the notion that the Native Americans were the keystone species in the Americas. For those unfamiliar with the concept, keystone species are essentially a lynchpin keeping an ecosystem healthy. When it’s removed, the system is thrown off balance. When native populations died off, the system was thrown into imbalance.

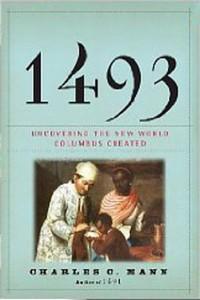

I anxiously awaited the opportunity to read Mann’s follow up, 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. While it’s been in print for a few years, I had been otherwise occupied. Finally I bought a copy earlier this year. I must say that it reads more slowly than I anticipated. I seem to recall breezing through the prequel. However, just like the precursor, I didn’t know what to expect. A main premise of the book is the impacts of the “Columbian Exchange”; the idea that various species were introduced to previously unfamiliar territory through ships criss-crossing the oceans bringing side species with them. This was the start of invasive species. Sometimes the evidence is a bit underwhelming, but it’s not for a lack of effort. Mann draws on a wide range of resources. His most interesting points connect to the environmental damage that seems to have preceded the industrial revolution in China. His argument in part is that food stocks introduced to China, namely sweet potatoes and maize, were ruinous for soil, led to erosion, and exacerbated flooding. Direct evidence is scant and the attempt to piece together results in an intriguing, but difficult to prove assertion. For instance, Mann ties the increasing misuse of land, which led to intense desertification to these flawed agricultural practices and more indirectly to the global silver trade. One reason I enjoyed 1491, and appreciate 1493, is the alternative to mainstream explanations. It is difficult to know whether nascent globalization is at fault, partly because it runs counter to the current paradigm.

Mann makes several other observations pertinent to ecological degradation. He brings forth the idea that the potato was partly responsible for the population explosion. Additionally, he posits the guano trade as a precursor to input intensive farming and resource reallocation. Guano from Chile was excavated, sold, and transported across the oceans to Europe, years before other industries caught on to extractive economies. In this instance Mann presents globalization at its core. Several other examples of the Columbian Exchange leading to invasive species and globalization come to light in 1493. It’s plausible to draw a straight line from the spread of invasive species like the Colorado potato beetle and potato blight to the rise of the chemical pesticide industry.

Mann addresses slavery and its roots as well. Large plantations and monoculture helped shepherd this dark chapter in human history. Furthermore, globalization and worldwide demand for consumer goods also played a significant role in deforestation and exploitation. Mann recounts the increase demand for products in the case of(Philippine Mahogany, a stand-in for its more exotic namesake.

Again and again new species becoming invasive ones can be seen no matter where or when organisms are introduced. Mann makes a compelling argument for the role of humans in altering the face of the planet after Columbus, even if it takes 690 pages (including notes).

** My intention was to link to Mann’s website, but curiously it does not have 1493 on it.

[Image]