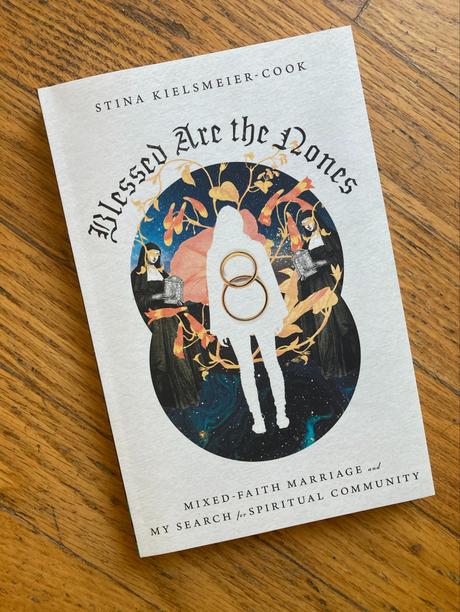

The most common, and the fastest-growing, type of interfaith marriage in the US is a marriage between a Christian and a "religious none." (The " nones" are a catch-all for anyone who doesn't check one religion box-whether an atheist, an agnostic, spiritual but not religious, or someone with many religious heritages). Whenever I give a talk on interfaith families, I always get questions from families navigating differences between religious and non-religious beliefs. Now, a lively, original, and moving new memoir describes just such a marriage for the first time, from the inside. Blessed Are the Nones: Mixed-Faith Marriage and My Search for Spiritual Community, is a deeply Christian book in many ways, but it touches on many of the emotional and practical hurdles faced by interfaith families of all types.

Stina Kielsmeier-Cook and her husband Josh, the son of a missionary, met at an evangelical Christian college, married, and spent time living off the land together in a Christian farming community. But a few years into their marriage, Josh announces that he has stopped believing in God. This book charts Stina's journey through adjusting to this new asymmetry in their relationship to Christianity. Seeking spiritual support and community, she engages with an order of Catholic nuns in their neighborhood in downtown Minneapolis, in an attempt to learn what it is like to be "spiritually single." But the nuns reject this term, and instead help Stina to feel connected to multiple communities, and to feel less alone by the end of the book.

The memoir follows a chronology through the seasons and the liturgical calendar of that first year after Josh leaves Christianity. Their two small children serve as minor characters, illustrating the universally messy reality and comic relief of parenting. But the focus of this memoir is Stina's struggles: to reimagine life without a Christian partner, to face her own doubts on religion and marriage, to find community, and to forge new relationships and religious growth with the nuns. Josh, rather than being the antagonist, is depicted as a mensch, often coming to the rescue to pick up Stina and the kids at church, and patient and considerate with his wife as she works to process his revelation. By the end of the book, she has traveled through shock and fear and grief at Josh's loss of religion, to an eventual sense of trust and peace and acceptance.

Stina is a seeker, ecumenical by nature, willing to learn from others, but with a perspective deeply rooted in the Protestant world. She describes her experiences as part of Presbyterian, evangelical, Mennonite, Episcopalian, and Baptist communities, and her enrichment through discovering Catholic liturgies, saints, and monastic life. For interfaith families who are not Christian, the language of believers versus nonbelievers, of being unequally yoked, of heaven and hell and salvation-may not resonate. By definition, this book will be most relevant for practicing Christians who have spouses who have left Christianity. And there are many.

Nevertheless, the book describes challenges that are common for interfaith couples, whether they are Christian and Jewish, or Pagan and atheist. What does it feel like to sit alone (or alone with children) in a place of worship, feeling that everyone else is sitting with a spouse? What does it feel like to feel exhausted by the burden of trying to transmit your religious heritage to children without a partner's participation? What does it feel like to realize your children may not go to your beloved childhood religious school or camp?

I admire the author's determination to capture this pivotal year while the experience was still fresh. As such, it will be most useful to other couples at the start of an interfaith relationship. On the other hand, those who have been in interfaith relationships for many years or decades may need to search their memories to recall some of the feelings described. The desire for a spouse to convert (or in this case, re-convert), expressed frequently in this book, may not be as familiar to those from non-proselytizing religions. And it is a feeling that has been faced and firmly put aside in many mature interfaith relationships. The strict binary of "faith" or "no faith," (again, a traditionally Christian-centric way of considering the concept of religious identity), often shifts in longtime interfaith relationships into a more complicated conversation. And many of us eventually shift away from the undue influence of societal insistence that interfaith families are problematic, to an appreciation for the benefits and richness that interfaith families can bring.

So I hope that Stina will report back some years from now on her fascinating journey with a sequel to this spiritual memoir. We have precious few books written from inside interfaith families, and even fewer by writers aspiring to literary non-fiction. In the meantime, I will be adding this book to my list of resources for interfaith families. It pairs nicely with Duane McGowan's more journalistic book In Faith and in Doubt, written from the point of view of an atheist married to a Christian, describing many such families. I am grateful to Stina Kielsmeyer-Cook for adding to the growing roster of authors from interfaith families who are chronicling our myriad experiences, and creating a new category in the world of books.

Journalist is an interfaith families speaker, consultant, and coach, and author of Being Both: Embracing Two Religions in One Interfaith Family (2015), and The Interfaith Family Journal (2019). Follow her on Twitter @susankatzmiller.