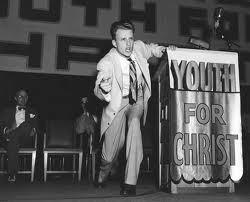

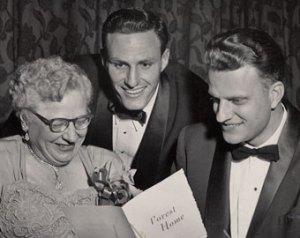

Billy Graham during his Youth for Christ years

It was August of 1949 and Billy Graham had never been so depressed. Twelve years after “surrendering to preach” on a Florida golf course, the evangelist was wrestling with doubts. He had been reading neo-orthodox theologians like Karl Barth and Reinhold Niebuhr, critics of liberal theology who freely admitted that the Bible was riddled with errors and internal contradictions.

But the nub of Graham’s problem lay closer to home. For the past four years, Graham had been working with Chuck Templeton, a brilliant and strikingly handsome preacher from Canada, on the evangelistic team with a fledgling Youth for Christ. Graham and Templeton had conducted a series of wildly successful crusades in post-war Europe in 1945 and had been fast friends ever since. But Chuck was fresh from his first year at Princeton Theological Seminary and that year had changed him.

Chuck and Billy had been invited to speak at the Forest Home, a retreat center established by First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood a decade earlier. Soon after their arrival, Templeton told Graham that his preaching was hopelessly out of date. This account of the conversation comes from Templeton:

“It’s simply not possible any longer to believe, for instance, the biblical account of creation,” Templeton argued. “The world was not created over a period of days a few thousand years ago; it has evolved over millions of years. It’s not a matter of speculation; it’s a demonstrable fact.”

“I don’t accept that” Billy replied stoically: And there are reputable scholars who don’t.”

“Who are these scholars?” Templeton asked. “Men in conservative Christian colleges?”

That question stung. At the time of their conversation, Graham was president of the unaccredited Northwestern Bible College founded by fundamentalist preacher W.B. Riley

‘Most of them, yes,’ Graham admitted, “but that is not the point. I believe the Genesis account of creation because it’s in the Bible. I’ve discovered something in my ministry: When I take the Bible literally, when I proclaim it as the word of God, my preaching has power. When I stand on the platform and say, ‘God says,’ or ‘The Bible says,’ the Holy Spirit uses me. There are results. Wiser men than you or I have been arguing questions like this for centuries. I don’t have the time or the intellect to examine all sides of the theological dispute, so I’ve decided once for all to stop questioning and accept the Bible as God’s word.”

‘But Billy,’ Templeton interjected, “You cannot do that. You don’t dare stop thinking about the most important question in life. Do it and you begin to die. It’s intellectual suicide.’”

“I don’t know about anybody else,” Graham answered, “but I’ve decided that that’s the path for me.”

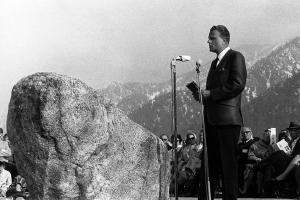

Graham preaches commemorative sermon on the spot where he made his fateful decision.

What happened next is the stuff of evangelical legend. Graham had put up a brave front with his Canadian friend, but the confrontation left his stunned. His first instinct was to seek the counsel of Henrietta Mears, the celebrated Bible teacher and evangelical visionary who had founded Forest Home ten years earlier. Bold, confident, and brimming, as always, with evangelical energy, Mears was just the tonic Graham needed. The inerrancy of Scripture was the bedrock of Christianity, she reminded the young evangelist. Undermine that foundation and the whole edifice collapses.

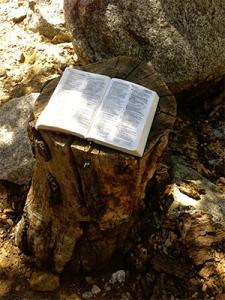

Graham picked up his Bible and wandered alone into the rugged hill country surrounding Forest Home. Spotting an old tree stump by the side of the path, Graham laid down his opened Bible, and began to pray.

“O God! There are many things in this book I do not understand. There are many problems with it for which I have no solution. There are many seeming contradictions. There are some areas in it that do not seem to correlate with modern science. I can’t answer some of the philosophical and psychological questions Chuck and others are raising.”

Graham fell to his knees.

“Father, I am going to accept this as Thy Word—by faith! I’m going to allow faith to go beyond my intellectual questions and doubts, and I will believe this to be Your inspired Word!”

With these words, Graham felt the Spirit of God flooding his soul. When he addressed the Forest Home audience the following evening, Henrietta Mears knew she was listening to a new man. There was a confidence, a sense of authority to his preaching that was utterly new and extremely powerful. A month later, the response to Graham’s Los Angeles crusade was so overwhelming that organizers added several additional nights to contain the crowds. Billy never looked back.

The “tree stump story” has been retold thousands of times across the years. Robert Jeffress, pastor of First Baptist Church, Dallas (the congregation Billy Graham joined in 1953) was once asked if he had ever doubted the Bible. Only once, Jeffress told the Dallas reporter.

The “tree stump story” has been retold thousands of times across the years. Robert Jeffress, pastor of First Baptist Church, Dallas (the congregation Billy Graham joined in 1953) was once asked if he had ever doubted the Bible. Only once, Jeffress told the Dallas reporter.

There was a time when he was a freshman at Baylor that he had a very liberal religion professor. The professor used to explain to the class that the Bible is filled with contradictions, that much of it is metaphor, just the best explanations people had thousands of years ago.

Jeffress had never before had any reason to doubt anything a teacher had ever told him. He told me he stopped reading the Bible so much. He lost his interest in bringing people to Christ. Over the next few months, the doubt grew. During Christmas break, he went to a mission conference where Billy Graham was talking. That night, Graham confessed to the crowd that there had been a time once when he doubted the inerrancy of the Bible. He said he found clarity on a golf course in Florida one day, knelt down on the spot, apologized to God, and decided he would never doubt the Bible again.

As he sat listening to the story, Jeffress felt like God had brought him there that night, brought him to hear this exact message. He decided right then and there that he would never doubt again. He even had Billy Graham sign and date his notebook that night.

Jeffress confused his dates and places a bit, but that’s the way folk tales work–the details hardly matter. The Dallas preacher grasped the story’s essential logic. Graham decided to believe the Bible and God blessed his ministry. If you want results, follow Billy’s example.

Everyone has heard of Billy Graham, he may be the most famous American of the 20th century (he’s certainly in the top ten). But, be honest, have you ever heard of (Chuck) Templeton?

Chuck Templeton preaching at a Youth for Christ Rally in New York

If you have, you’re probably a Canadian and you know him as Charles, not Chuck. When I was growing up in Edmonton, Templeton’s handsome visage graced Canadian television news programs (often in the company of his good friend, Pierre Burton). And every time he popped up on the tube my mother would tell me what a wonderful preacher Charles Templeton had been before he went to the devil.

Google Templeton’s name today and you will find a series of cautionary tales contrasting the trajectories of the man who believed the Bible and the smarty-pants who questioned God’s word.

The real story is a bit more complicated than that. Actually, it’s a lot more complicated.

Chuck Templeton didn’t grow up in the warm embrace of southern evangelicalism like Billy Graham. Billy attended Bob Jones University in South Carolina before transferring to the warm embrace of Wheaton College, an evangelical hot house west of Chicago. There he married Ruth Bell Graham, the daughter of famous (and well-connected) Presbyterian missionaries. As a young man, Graham was embraced by the evangelical/fundamentalist world across the nation and through out the world.

Billy Graham’s conversion story is pretty standard fare–in 1934, the young North Carolinian responded to an altar call delivered by an evangelist named Mordecai Ham, an independent Baptist evangelist who hated booze, Jews and Catholics. For a southern boy raised in the bosom of the church, nothing could have been less surprising. (Ham would eventually introduce Graham to W.B. Riley, the most influential fundamentalist preacher in America.)

Billy Graham’s conversion story is pretty standard fare–in 1934, the young North Carolinian responded to an altar call delivered by an evangelist named Mordecai Ham, an independent Baptist evangelist who hated booze, Jews and Catholics. For a southern boy raised in the bosom of the church, nothing could have been less surprising. (Ham would eventually introduce Graham to W.B. Riley, the most influential fundamentalist preacher in America.)

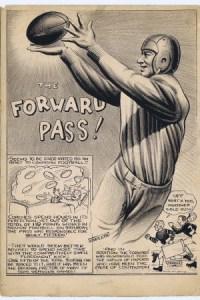

Chuck Templeton, by way of contrast, grew up on the margins of American evangelicalism. The child of a single mother, and with only a ninth-grade education, Templeton was hired by the Toronto Globe as a sports cartoonist (yes, that used to be a job). Chuck grew up in grinding poverty, but his mother coped much better when she joined a Nazarene Church and gave her heart to Jesus.

Initially, Templeton had little interest in religion and his life, not surprisingly, revolved around women, work, smoky bars and parties. One night, Templeton arrived home at three in the morning after a dismal social affair featuring a listless stripper. He caught his reflection in the mirror and didn’t like what he saw. He stopped in to chat with his mother who, as always, wanted to talk about the difference God had made in her life. She told him how happy she would be to see him in church with the other young people.

As she talked, Templeton was taking moral inventory, feeling more depressed with each passing moment. Excusing himself, he wandered down the hall to his room, a garbled prayer forming in his head. What follows beats the hell out of Billy’s conversion story.

As I knelt by my bed in the darkness, my mind was strangely vacant; thoughts and words wouldn’t come to focus. After a moment, it was as though a black blanket had been draped over me. A sense of enormous guilt descended and invaded every part of me. I was unclean.

Involuntarily, I began to pray, my face upturned, tears streaming. The only words I could find were, “Lord, come down. Come done. Come down. . . .”

It may have been minutes later or much longer – there was no sense of time – but I found my head in my hands, crunched small on the floor at the center of a vast emptiness. The agonizing was past. It had left me numb, speechless, immobilized, alone, tense with a sense of expectancy. In a moment, a weight began to lift, a weight as heavy as I. It passed through my thighs, my belly, my chest, my arms, my shoulders and lifted off entirely. I could have leaped over a wall. An ineffable warmth began to suffuse every corpuscle. It seemed that a light had turned on in my chest and its refining fire had cleansed me. I hardly dared breathe, fearing that I might end or alter the moment. I heard myself whispering softly, over and over, “Thank you, Lord. Thank you. Thank you. . . .”

After a while I went to mother’s room. She saw my face, said, “Oh, Chuck. . !” and burst into tears. We talked for an hour.

This was the first of many occasions in which Templeton’s will and reason would be temporarily overwhelmed by a mystical wellspring buried deep in his soul (or his unconscious mind, if you’re not born-again).

Templeton resigned his job as a sports cartoonist, bought an old car, and started preaching wherever he could get an invitation. His reputation grew rapidly and he soon found himself turning down invitations. Eventually, he married his winsome soloist and the audacious couple purchased an abandoned church in Toronto. The church filled to capacity in a matter of months . . . it burned to the ground . . . the congregation rebuilt it.

Chuck Templeton (left) and Billy Graham (bottom right) evangelize wayward young people

Before long, Chuck Templeton was barnstorming the United States and Canada. He regularly filled Toronto’s Massey Hall and on several occasions preached to a crowd of 16,000 in the iconic Maple Leaf Gardens. His 1945 tour of Europe with an equally charismatic Billy Graham was an unmitigated triumph and there is even a hilarious story in which our young heroes spent a wild evening with two French prostitutes without surrendering their virtue (go figure).

Not all of Templeton’s evangelistic bookings panned out, of course. In a dismal little hamlet in Michigan, for instance, the preacher found himself in the home of “a neurotically shy, shrivel-souled, skinny little man, a secret smoker who reeked of tobacco and whose fingers had a mahogany hue. When anyone spoke to him his face would flush and the acne he was cursed with would flame.”

But the man possessed an extensive and eclectic library with an entire section dedicated to the work of skeptics and infidels.

An omnivorous reader since childhood, Templeton had never read any serious philosophical or theological work. That changed quickly.

I picked up Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason. In a few hours, nearly everything I knew or believed about the Christian religion was challenged and in large part demolished. My unsophisticated mind had no defenses against the thrust of his logic or his devastating arguments.

In the next ten days I read Francois Voltaire’s The Bible Explained at Last, Bertrand Russell’s Why I am Not a Christian, the speeches of great American atheist, Robert Ingersoll, including his The Mistakes of Moses, and dipped into David Hume and Thomas Huxley.

Each evening, after a day of obsessive reading, Templeton would mount the pulpit of the local church, stumbling through a sermon with Huxley and Ingersoll still thundering in the back of his brain. A man with an ninth-grade education had lived for years in the warm embrace of an evangelical subculture where the verities of the faith (the divinity of Christ, eternal rewards and punishments and the trustworthiness of the Bible) were constantly affirmed. Suddenly, he found himself wrestling with the most devastating critiques of Christian orthodoxy ever written.

Templeton recovered from this first crisis of faith, but the questions wouldn’t go away. The celebrated evangelist didn’t have a trusted friend of a safe place where dangerous ideas could be kicked around. Then a friend suggested he should enroll in seminary. The idea struck Templeton with the force of an epiphany.

After some cajoling from Templeton’s friends in the United Church of Canada, Princeton Theological Seminary agreed to accept him as a “special student”. They couldn’t give him a degree because he lacked the required bachelor’s degree, but he was free to enroll for coursework. That was fine with the Canadian evangelist; he wasn’t looking for academic credentials; he just wanted a safe place to wrestle with the questions crowding his mind.

In the summer of 1948, just before classes began in New Jersey, Templeton dropped in on Billy Graham at his friend’s home in Montreat, North Carolina. As president of an unaccredited college, Graham had been toying with the idea of getting an advanced degree himself, but it couldn’t be in the United States, he said. Wait a year, Graham suggested, and they could attend Oxford together.

Templeton liked the idea, but he realized he was lucky to find a place at Princeton and doubted Oxford would be as flexible. He tried again to get Billy to drop everything for a few years and join him at Princeton. “We’ve been getting by on youthful energy and animal magnetism,” Templeton said, “and we need to develop some academic backbone.”

A year later, with his freshman year at seminary, and just enough of Schweitzer, Barth, Bultmann and the Niebuhr brothers to be dangerous, Templeton was at the Forest Home Retreat Center telling Billy Graham that his theology was fifty years out of date.

What would have happened if Billy had joined Chuck at Princeton? The question is moot. Both men knew that Graham’s simple biblicism couldn’t withstand the kind of free-flowing theological debate he would have encountered at a liberal seminary. Graham’s theological education was deficient, and he knew it, but he needed the support of the American evangelical tribe more than he needed an advanced degree.

In their Youth for Christ days, Templeton and Graham were confidence men. Their job was to speak with the authority of God Almighty to untutored men and women looking for something to get them through the night. People weren’t looking for finely-honed theological prose or nuanced academic debate; they just wanted to know that God was in control, heaven was waiting on the far side of suffering, that the Bible could be trusted, and that Jesus Christ was the Lamb of God who taketh away the sins of the world.

Everybody knew what Billy Graham was going to say before he said it; they came for the conviction in his eyes and the authoritative timber in his voice. Graham spoke for the Bible, he spoke for God, and he made every count. The slightest ambiguity or hint of irony would destroy the effect.

Which is why Billy Graham had no choice but to lay his Bible on the tree stump and swear to God that he would preach an inerrant Bible so long as he lived. It’s what everyone expected from him; more to the point, it was what God expected. God wants his preachers to believe the Bible even when it sounds mean or crazy. If there was one single contradiction or error in the Good Book, evangelicals insisted, the Bible was a worthless document, Jesus was just another Jewish Rabbi, heaven was a pipe dream and God was effectively dead.

Henrietta Mears with Billy Graham

Billy Graham believed in his evangelical subculture. Sure, the tribe had its share of cranks, misfits and social pugilists, but Graham could count on saints like Henrietta Mears, men and women (mostly women) raised in Godly homes who knew half the Bible by heart and bet their very lives on its integrity. These saints were intelligent, dedicated, loving and joyful people, living proof of the gospel’s transformative power. They, and the families they created, couldn’t be found outside the evangelical community. The spread of evangelical culture was the hope of America; the death of that culture would be the death of everything men like Billy Graham held dear.

Short months after returning for his second year of seminary, Templeton had his own dramatic encounter with God (and, yes, it beats the hell out of Billy’s tree stump story). It was year after Mohandas Gandhi had been assassinated in India and Templeton was mesmerized by the non-violent revolution Gandhi had unleashed. Following the Indian leader’s example, Templeton started fasting every Wednesday, taking nothing but a little water. Every evening he would walk the length of the golf course near his home, wrestling with God; looking for a sign.

In his autobiography, published in 1983, Templeton described the incident.

One night I went to the golf course rather late. I had attended a movie and something in the film had set to vibrating an obscure chord in my consciousness. Standing with my face to the heavens tears streaming, I heard a dog bark of in the distance and, from somewhere, faintly, eerily, a baby crying. Suddenly I was caught up in a transport. It seemed that the whole of creation–trees, flowers, clouds, the sky, the very heavens, all of time and space and God Himself-was weeping. I knew somehow that they were weeping for mankind: for our obduracy, our hatreds, our ten thousand cruelties, our love of war and violence. And at the heart of this eternal sorrow I saw the shadow of a cross, with the silhouetted figure on it . . . weeping.

When I became conscious of my surroundings again, I was lying on the wet grass, convulsed by sobs. I had been outside myself and didn’t know for how long. Later, I couldn’t sleep and trembled as though with a fever at the thought that I had caught a glimpse through the veil.

The experience came unbidden and, although Templeton continued his fasting and evening walks, his mystical encounter was not repeated. Templeton dealt with his epiphany by heading to the library. There he discovered that “what had happened to me was not unusual: it has been a commonplace at various times in the history of the church. More important, I learned that it was of no special significance. Mystical experience has added no insight to our knowledge of God or to Christian doctrine.”

David Vance wrote his Master’s Thesis at Carleton University on Templeton’s “performance of unbelief” and he says he was floored by this dismissive comment (especially the bit I have emphasized). As am I. Templeton’s vision bristled with theological significance. This portrait of a God weeping for (and with) a creation disfigured by mindless violence anticipates Jurgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God. Theological reflection doesn’t get any deeper than this.

In 1983, the year Templeton published his autobiography, my wife and I were in Victoria, British Columbia visiting with Gipp Forster, a former street person who had established a church of street people for street people. Gipp was knee deep in organized crime when he attended a Billy Graham crusade and turned his life over to God.

Gipp was earthy and could profane when the fancy struck him, but he had a gift for preaching. I once heard him tell his congregation that their Jesus was too neat and tidy. “When Jesus finally got to Jerusalem, he had been on the road for days and his face was caked with the dust of the road he walked. When he saw the Holy City in the distance, and those big tears came rolling, they formed little streams of mud down his face. This shit is real, folks!”

I went home and wrote a song inspired by that image.

Weeping for Jerusalem,

weeping for the race,

dust and sorrow mingling

in mud tracks down his face.

Children, look at the man,

he’s weeping for you.

A weeping God is the only answer to the problem of evil we are likely to get in this through-a-glass-darkly world. We can’t know why God allows dreadful things to happen to innocent people; but Templeton’s vision points us in the right direction. God weeps for the world. God lives himself into the pain of the world. That’s what the cross means. God suffers with us. God dies with us. We die with God. We are raised with God. That’s the Christian story. It might not have been the story Chuck Templeton was converted into; but when Billy Graham-style theology no longer worked for him, it would have made a wonderful alternative. Why couldn’t he see that?

In his dissertation on Templeton, David Vance notes that, even in his days as a celebrated evangelist, Templeton presented himself as rational, controlled and logical.

Templeton was effectively tapping into prevalent cultural concerns regarding an increasingly threatened gender hierarchy, and establishing himself as the epitome of what Chris Dummitt calls the “manly modern” – the man who effectively masters and manages the pervading risks inherent to postwar society. Rationality was certainly one celebrated feature of this modern form of masculinity, for it embodied a clean and logical way of ordering reality (as opposed to the more inconsistent, emotional quality assumed of women).

Perhaps, but Templeton was also reflecting the theological zeitgeist of the day. In liberal seminaries, it was widely assumed that you resolved any apparent tension between faith and reason by siding with reason. The theologians of the mid twentieth century wrote as if the Bible was inspired by human fear, love and longing. Some theologians and biblical scholars were openly agnostic, others saw Jesus as the epitome of Israel’s “prophetic tradition” (which was a good thing). But theologians were interested in recreating the mechanics of religious thought in various times and places: comparing, contrasting and theorizing. There was no “Thus saith the Lord” allowed and personal observations about the nature of God, were considered outside the purview of serious scholarship. Miracles were dismissed as the stuff of legend. Logical positivism, the idea that meaning resides in empirical facts alone, was the prevailing fad in philosophy and its ethos pervaded most academic theology.

Christian mysticism, as Templeton’s research indicated, was generally treated as an historical curiosity, a fitting subjects for psychologists, maybe, but not for theologians. There was academic theology and there was the kind of superficial devotional material Templeton deplored . . . and very little in between. This partially explains the phenomenal success C.S. Lewis enjoyed in America at mid-century–his practical exposition, written in simple but elegant prose, filled a gap and fed a hunger.

Charles Templeton had the mind of a rationalist and the soul of a mystic; an internal contradiction that made him miserable.

Still, the three years Templeton spent at Princeton were among the most enjoyable of his life. A passionate student with a sharp mind, he quickly rose to the head of his class. Initially, the seminary tried to give him a diploma instead of a degree, but his academic success made the school look petty, so they relented.

Templeton was now a hot commodity. When he graduated in 1951, North America was at the height of a religious revival that would last another decade. Eager to exploit the post-war hunger for spirituality, respectability and, above all, normalcy, the churches of the Protestant Mainline (Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, United Church of Canada, United Church of Christ, American Baptist, etc.) were looking for an evangelistic message that avoided the heaven-hell dualism of a Billy Graham crusade.

Most of the men (and they were all men) at the helm of these denominations were veterans of the social gospel movement. They were comfortable with the language of evangelical piety, but they believed the gospel should shine a spotlight on contemporary issues like poverty, racial harmony, and the vexed relationship between management and labor. Veterans of the Second World War, and the women who kept the home fires burning during those hard years, were eager to settle down, raise families and move up the socio-economic ladder. Templeton, with his on-the-ground experience with mass evangelism, his dynamic public presence, and his Princeton divinity degree, was the man of the hour.

First, Templeton was hired as the official evangelist of the National Council of Churches, an ecumenical organization formed in 1950 as a new-and-improved version of the older Federal Council of Churches. A 1953 article by Edward Boyd, written for the American Magazine, captures the excitement the Canadian phenom generated in the early 50s:

There was an unmistakable element of hope and optimism in all he said. Religion was no longer a solemn, formal, worn-out thing with all the appeal of the graveyard. It was, on the contrary, happy, warm, and vital. He presented it as a challenge and an exciting way of life.

Since I represent a new generation, it may be that his appeal to me explains his success with so many others. His comparative simplicity of approach, his natural presentation of Christianity as a commodity as necessary to life as salt, and his overwhelming belief in its practical value “sold” me.

During this period, Templeton wrote three books on evangelism, still emphasizing the necessity of authority, clarity, and theological simplicity. It didn’t matter what the evangelist believed about the age of the earth, the historicity of the creation accounts, Joshua stopping the sun, or Noah and his ark, but a firm belief in the divinity of Christ remained essential. This excerpt is typical of his work:

“To this hungry, confused and wandering generation . . . the church comes with the ‘good news’ of God. Let it be a church renewed in commitment to Christ and to his gospel! Let it be a church afire with the evangel and moving out to do its leavening and redemptive task! Let the grace of our God be heralded with no uncertain sound, and let us look with confidence to God to revive his church in the midst of these years!”

Templeton sloughed off his mystical encounter on a Princeton golf course partly because he was a rationalist who didn’t like losing control. But his vision of a weeping God was also rejected for pragmatic reasons: there was no market for that sort of thing, no natural constituency. Templeton wanted to bring fire, enthusiasm, confidence and hope to his audience; a crucified God weeping for a warlike creation hardly fit the bill.

During these years, Templeton was searching for a message that was both rational, biblical and inspiring. Unlike Billy Graham, he didn’t want to fall on God’s two-edged sword in an act of intellectual suicide; but he wanted to see people changed, he wanted to make them better, stronger, more positive, effective and hopeful. But when you move past the “Jesus died on the cross to save your soul from hell” message, what remains? Templeton’s new-improved gospel was little more than a means to an end–a sure-fire path to happiness. And deep down where the visions lived, he knew it.

Templeton emerged as the thinking man’s evangelist just as television was taking North America by storm, and it wasn’t long before he was the star of Look Up and Live, a Sunday morning program featuring interviews with celebrities and snappy religious pep talks from Templeton. Had he continued in this vein he might have become a kinder gentler Billy Graham; but Templeton was living on borrowed time.

Templeton described his decision to quit the church and his rational faculty whittling away at his faith until nothing remained. That explanation doesn’t fit the evidence. Millions of Christians make the transition from fundamentalism to more liberal forms of Christianity without abandoning God or the Bible. Some even move from atheism to fundamentalism. Why, then, was it so hard for the clever, charming, articulate and photogenic Chuck Templeton to stick with the church he loved?

The likely answer is that he no longer loved the church or his role in it. He had swapped Billy Graham’s version of Christianity for a liberal alternative, but it didn’t take. He didn’t believe in the Jesus who promised success and happiness any more than he believed in the Jesus who rescues souls from hell. Since these were the only religious commodities on offer, Templeton began to feel like a sharlatan.

Templeton’s body signaled that a religious war was raging in his soul long before his intellect got wind of the problem. In the pulpit, Chuck preached with the same old fire and conviction and received the same rapturous response. But chest pain became his traveling companion accompanied by restricted breathing. When Templeton was finally examined by a doctor, the diagnosis came as a shock. (This is from his Memoir):

“There is nothing wrong with your heart. Nothing. The pains you get – let me put it in layman’s language – are the result of what I’ll call heart spasm. But the trouble isn’t in your heart, it’s in your head. There is something in your life that is bothering you. Some conflict. Some unresolved problem. Whatever it is, deal with it. Otherwise, you will probably continue to suffer the symptoms you have described to me and will likely see other manifestations.”

In the next few weeks, Templeton decided to quit preaching, leave the church, renounce his faith, and move from New York to Toronto. The backlash was immediate. This is what happened, former friends concluded, when you get on that slippery slide of liberalism. Predictably, his marriage fell apart. Preaching could have made him a wealthy man, but, for ethical reasons, he had restricted himself to a modest salary of $7,500 a year and was living month-to-month. He holed up in a cramped apartment in Toronto and started churning out screen plays for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

It wasn’t long before Canada’s most famous apostate was working as a hard-nosed interviewer on Canadian television. Presenting himself as an advocate for the ordinary Joe, Templeton used his insider’s knowledge of the religious world to skewer the leading religious figures of the day. In a 1962 interview on Close Up, Templeton asked Sir George MacLeod, a liberal Protestant and former Moderator of the Church of Scotland, to explain the gospel to him. MacLeod gave the expected response: the gospel is all about loving one another, making room for everyone, tolerating differences and showing compassion. Templeton’s response is telling:

“If a relatively simple person wanted to find out what he needed to do to find faith, I think you could argue that Billy Graham – with whom I profoundly disagree – that Billy Graham would give an answer which is much more useful than would the thoughtful church of which you’re a representative. Now, is it possible to communicate what you’ve been saying to me here, is it possible to communicate this and make it live? I don’t think it is, and I think this is one of the reasons why the church isn’t making an impact.”

Templeton wasn’t disagreeing with MacLeoud’s message; he simply didn’t think it would sell. Like it, or hate it, there was a market for Graham’s gospel; but MacLeoud and his kin were putting people to sleep and that, to an entertainer like Templeton, was unforgivable.

Having made his mark in broadcasting, Templeton tried his hand at newspaper and magazine publishing and eventually emerged as a successful novelist, an occupation that placed him on the opposite side of the microphone. In 1977, Jane Pauley came to an interview on the Today show unprepared and, in Templeton’s opinion, covered up by going on the attack. His reconstruction of the interview follows:

“I understand you ‘re an atheist, ” she said.

I explained that, no, I wasn ‘t an atheist but an agnostic, a very different thing. I really didn ‘t want to get into it; we had only seven minutes and I wanted to promote the book. I’d come five hundred miles to do that.

“But you don’t believe in God, ” she said, her face mirroring distaste.

“Nor do I disbelieve, ” I said. “I just don’t know. ”

“But you were a preacher.”

“Yes I was.”

“Well then, let me ask you this: are you happy? How can you be?”

She was doing her twenty-four-karat-earnest bit, looking deeply into my eyes. I looked back into hers for a moment, irritated, tempted to say, “You silly girl – what in God’s name has believing in God got to do with being happy?” I restrained myself and said the same thing in a more judicious way.

“What in God’s name has believing in God got to do with being happy?” An fascinating question from a man who once sold faith in God as a sure-fire path to happiness. Jane Pauley, the quintessential American, was working from the assumption that once shaped Chuck Templeton’s philosophy of preaching: people want to be happy. Applied to preaching, that transformed God into a commodity; a means to an end.

In 1995, six years before his death, Canada’s famous apostate penned his last book: Farewell to God, a thoroughly derivative rehashing of well-worn arguments from Robert Ingersoll, Bertrand Russell, and the usual list of suspects.

The book’s lack of originality may have been an early sign of the Alzheimer’s disease that raised its ugly head shortly after Farewell to God appeared in print. Templeton fought Alzheimer’s with all the ingenuity he could muster, even asking people to feed him complex words so he could spell them backwards. It helped, his family believes, but nothing could stop the deadly advance of this cruel disease.

Three years after Farewell to God appeared in bookstores, Lee Strobel, an American apologist and religious writer, called Templeton requesting an interview. The old man, now on his third marriage and given to intermittent periods of confused depression, gave his grudging accent.

Charles Templeton in is last years

Strobel had made the painful transition from agnosticism to evangelical Christianity and wanted to know why a former associate of the renowned Billy Graham would make that trek in reverse. The American was greeted at the door by Templeton’s wife, Madeleine, who wasn’t at all sure her husband was up to a lengthy interview. But he made an entrance wearing brown pajamas and a housecoat and settled into a comfortable chair.

The interview took a predictable course with the renowned skeptic limning out the case for agnosticism. He stumbled over a word or two and sometimes forgot a familiar name, but his command of language was strong and his wit remained intact.

Finally, Strobel cut to the chase: what did Templeton make of Jesus? (I quote extensively from Strobel’s account):

Templeton’s body language softened. It was as if he suddenly felt relaxed and comfortable in talking about an old and dear friend. His voice, which at times had displayed such a sharp and insistent edge, now took on a melancholy and reflective tone. His guard seemingly down, he spoke in an unhurried pace, almost nostalgically, carefully choosing his words as he talked about Jesus.

“He was,” Templeton began, “the greatest human being who has ever lived. He was a moral genius. His ethical sense was unique. He was the intrinsically wisest person that I’ve ever encountered in my life or in my readings. His commitment was total and led to his own death, much to the detriment of the world. What could one say about him except that this was a form of greatness?”

I was taken aback. “You sound like you really care about him,” I said.

“Well, yes, he is the most important thing in my life,” came his reply. “I . . . I . . . I . . . ,” he stuttered, searching for the right word, ‘I know it may sound strange, but I have to say . . . I adore him! . . . Everything good I know, everything decent I know, everything pure I know, I learned from Jesus.

“And tough! Just look at Jesus. He castigated people. He was angry. People don’t think of him that way, but they don’t read the Bible. He had a righteous anger. He cared for the oppressed and exploited. There’s no question that he had the highest moral standard, the least duplicity, the greatest compassion, of any human being in history.

“In my view,” he declared, “he is the most important human being who has ever existed. And if I may put it this way,” he said as his voice began to crack, ‘I . . . miss . . . him!”

With that tears flooded his eyes. He turned his head and looked downward, raising his left hand to shield his face from me. His shoulders bobbed as he wept. . . .

Templeton fought to compose himself. I could tell it wasn’t like him to lose control in front of a stranger. He sighed deeply and wiped away a tear. After a few more awkward moments, he waved his hand dismissively. Finally, quietly but adamantly, he insisted: “Enough of that.”

Strobel made several unsuccessful attempts to get Templeton back on the subject of Jesus. Canada’s most famous skeptic has spoken from his mystic soul and the rational side of his temperament was embarrassed into silence.

Reading Templeton’s rapturous ode to Jesus, questions clamor for attention. If Jesus was such a singular figure, how do we account for that transcendence? Was it a fluke? Was Jesus a religious genius in the Gandhian sense, or was Gandhi great because, like Martin King, he put the words of Jesus into action?

Templeton lost his religion when he was no longer able to confess the divinity of Jesus. Fair enough. But why couldn’t he work in the other direction, declaring that all we can know of God is what we see in Jesus?

Or, if that’s pushing the theological envelope too aggressively for you, why couldn’t Templeton, agnostic that he was, decide that since we can’t know anything about God, we should dedicate ourselves to the highest and best thing we can know?

For some reason, that path didn’t work for Charles Templeton. Loving Jesus with a smoldering passion, he turned his back on God. More than that, he spoke of God with contempt, declaring him dead and spitting on his grave. It seems to have been something he had to do, but why?

I can only conclude that, in Templeton’s view, you either believed in the God of Billy Graham or, if that raised too many logical and ethical questions, you said farewell to God altogether. In the end, neither Billy nor Chuck could believe that Jesus redefines the nature of God. Billy’s biblicism implicated Jesus in the most vengeful portraits of God on display in Leviticus, Joshua and the Book of Revelation. Templeton couldn’t let Jesus define God because that vision of God was unmarketable or, more to the point, it lacked a constituency.

Our story is almost over, but I have one more story for you. Fast forward to Charles Templeton’s penultimate day on earth. He had been combative and angry, lashing out at the hospice nurses charged with his care. When Madeleine arrived, Charles settled back into his bed. Toronto Star columnist, Tom Harpur, gave this account in his weekly column:

Suddenly, Madeleine said, he became very animated, looking intensely toward the ceiling of the room, his eyes “shining more blue than I’d ever seen before.”

He cried out: “Look at them, look at them. They’re so beautiful. They’re waiting for me.

“Oh, their eyes, their eyes are so beautiful!”

Then, with great joy in his voice, he said: “I’m coming.”

Madeleine told Harpur that the experience was “such a tremendous comfort . . . something transcendent and wonderful.” Charles Templeton died the following day.

Hallucinations aren’t unusual for patient’s in the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s, of course, so his vision on angels may not tell us much about what goes on behind the veil. But hallucinations emerge from the dark recesses of the subconscious, they work with the material at hand, and this instance is no exception.

Tom Harpur ended his column with a remembered conversation he had with Templeton around the time of the Lee Strobel interview in 1998. Since Harpur (a bit of a theological gadfly himself) and Templeton were old friends, the tenor of the conversation was much more relaxed:

Before I left, he rather wistfully showed me an old, Scotch-taped Bible. Thick and heavy, it was the one he always preached from in his crusades, he noted.

We talked of many things, including mutual friend Billy Graham and the future of religion.

I said that from watching him (often from afar) for most of my life and reading all his books, I felt deeply that he was a God-haunted or God-obsessed man in his inner being.

He said: “Yes, I would say that’s true.”

It was true. And now, if my gospel has it right, Chuck Templeton has moved through the dark glass of this world that land where we know even as we are known. The rest of us struggle on meanwhile, freighted with questions and insoluble dilemmas. And soon Billy Graham, his body no longer wracked with Parkinson’s disease, will be comparing notes with his old friend, Chuck. Please God, may it be so.