In 1953, during the heydays of Ivy Style, The New York Times surveyed a group of college grads to find out what they thought of the Ivy Look. Opinions were decidedly mixed – with pro and anti views somewhat falling along gender lines (men liked it; women didn’t). The main criticism seemed to be that the sack suit and soft-shouldered tweed made men look like Madison Avenue lemmings. One women said, “They’re so enslaved by conformity that when up and about, they all look as they’d been hacked out by the same die.” Another: “If we are all going to be tailored in the same pattern, we shall end up as dull, dreary, and disappointing as the man in the gray flannel suit.”

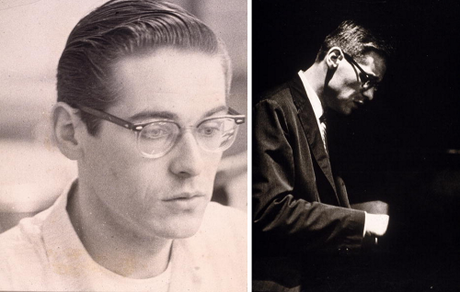

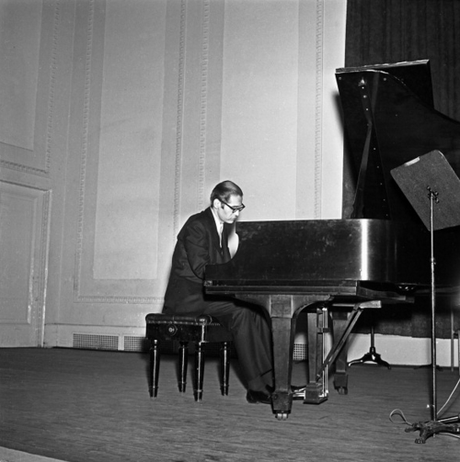

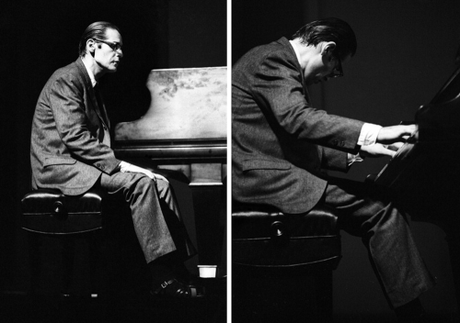

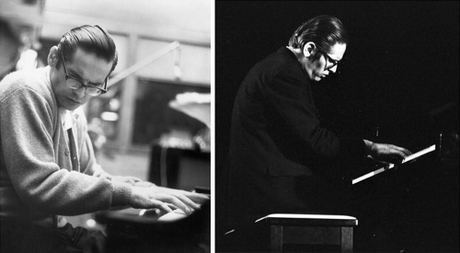

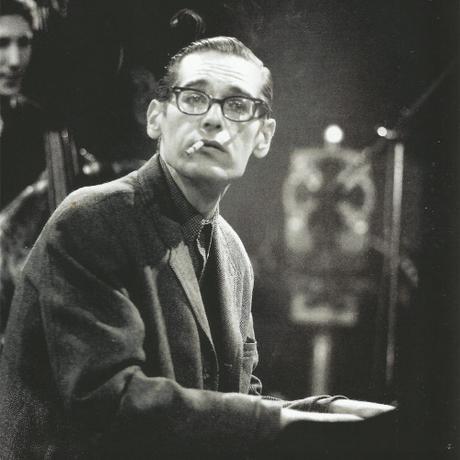

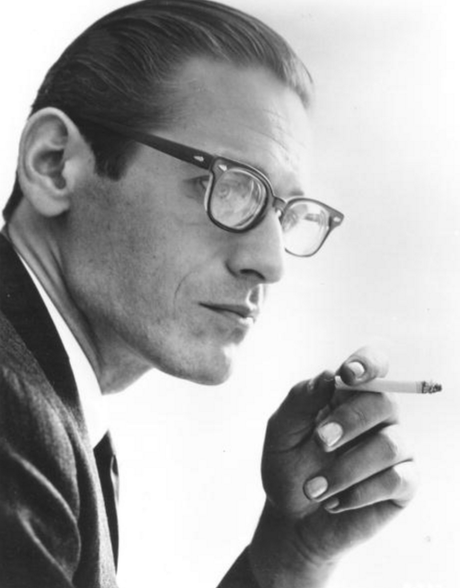

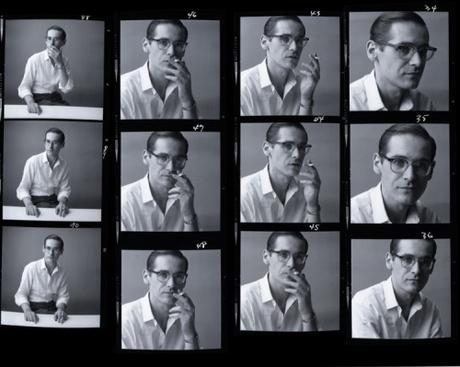

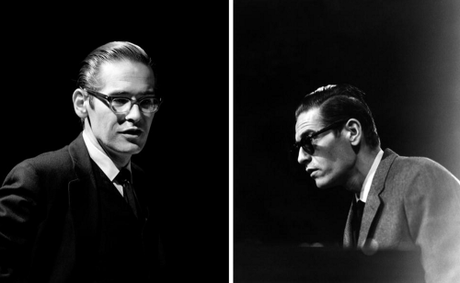

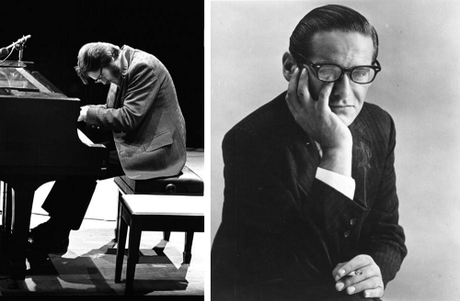

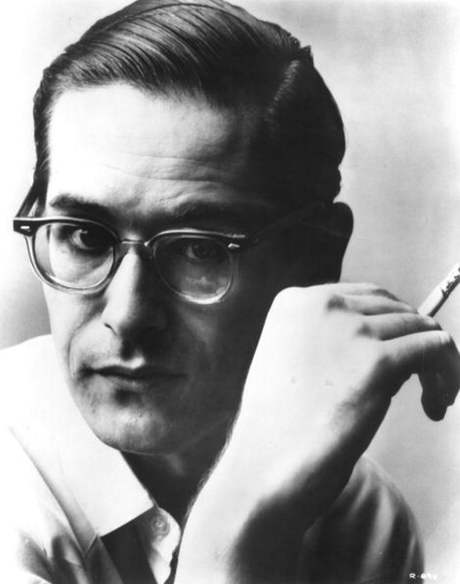

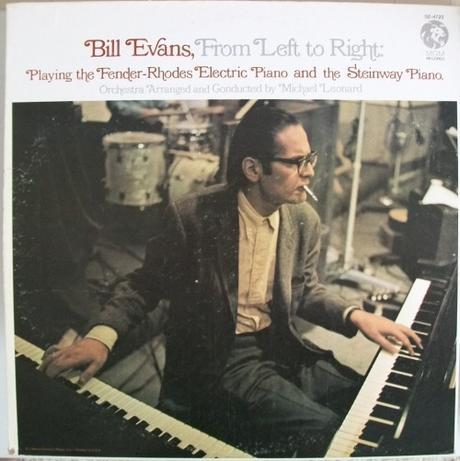

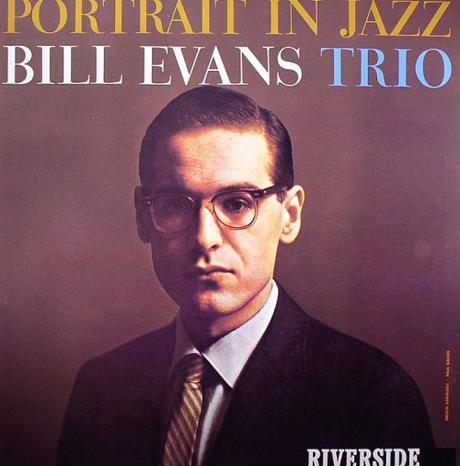

Although that’s probably true by and large, there are lots of jazz musicians who would serve as nice counter examples. My favorite is Bill Evans, who like many of his contemporaries during the ‘50s and ‘60s, dressed head-to-toe in Ivy. When he performed, he wore soft-shouldered sack suits (sometimes with Brooks Brothers’ signature two-button cuffs), along with dark ties and spread-collar white shirts. No pocket square or loud patterns, just the occasional tie clip. Despite the anonymity of his uniform, Evans looked anything but.

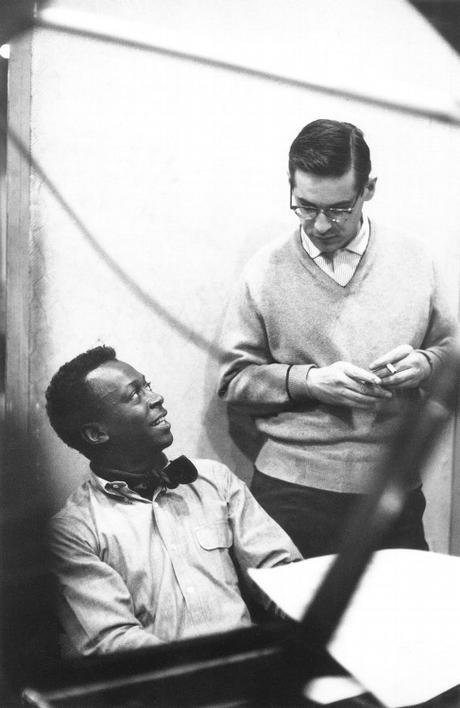

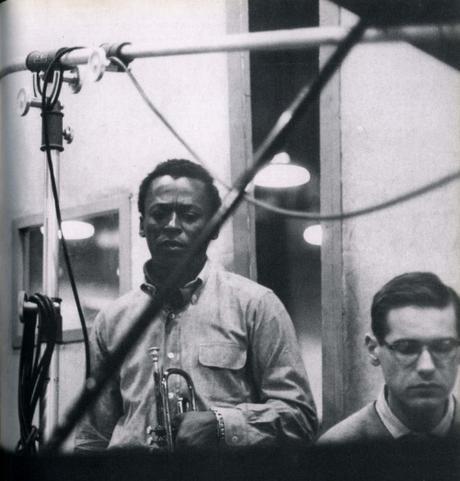

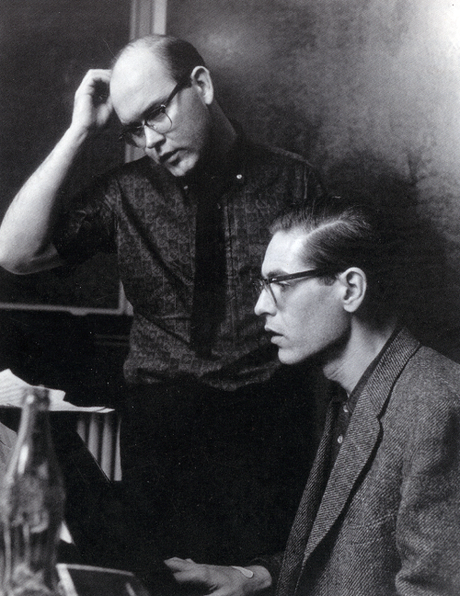

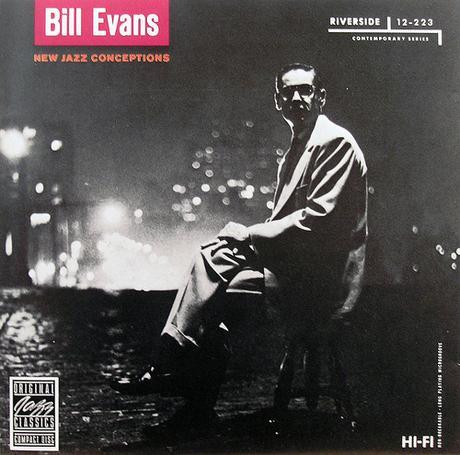

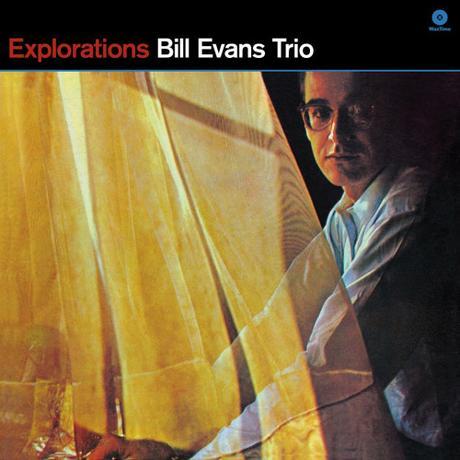

A lot of this can be chalked up to Evans’ good looks and talent. He was one of the most legendary jazz pianists of the 20th century, playing alongside such greats as Miles Davis and Cannonball Adderley. Non-jazz fans will probably know him from Kind of Blue (the soundtrack of every coffee shop), although I like him most for his work with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian. In fact, I started wearing browline glasses ten years ago partly because of Portrait in Jazz (the trio’s first album), where Evans sported a pair.

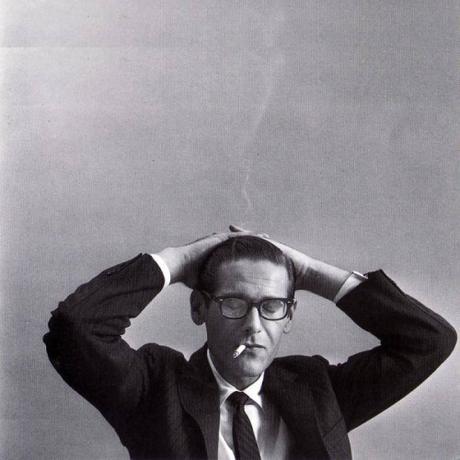

There’s also the fact that Evans wasn’t a conformist, which affected how his clothes looked. The painfully shy pianist dealt with his anxieties – which were fueled by his feelings of inadequacy, as well as his brother’s suicide following a long struggle with schizophrenia – with a lifetime of drug use. Evans was saddled with a heavy heroin addiction for most of his life, but it was cocaine that killed him in the end. In his book, Peter Pettinger writes about how Evans once played Johnny Mandel’s “Theme From M*A*S*H” in a San Francisco nightclub, remarking that the song was also known as “Suicide is Painless.” “Debatable,” he then dryly added.

Two weeks later, he was dead. Canadian music critic Gene Lees would later describe Evans’ struggle with drugs as the longest suicide in history.

I don’t mean to romanticize drug use or mental health issues, only to say that Evans is a good example of fashion’s most elusive tenets – that style is ultimately about attitude. Evans sported the uniform of every clean-cut, IBM drone, but his look was that of a tortured artist. I like how Christian Chensvold put it once: “Two men wearing the same outfit do not produce the same effect. A square in hip clothing is still a square, while a hipster in square clothing is still hip.”