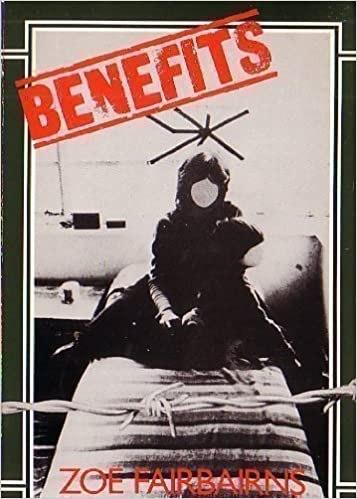

Last week I was on holiday in Devon, and while browing a lovely second hand bookshop in Topsham (a very pretty town on the River Exe estuary – well worth a visit!), I came across an entire bookshelf filled with Viragos. These weren’t just the usual Viragos; there was a huge collection of very early ones, in a design and by authors I didn’t recognize. Intrigued, I spent some time reading the blurbs to find out more, and ended up walking away with one that sounded like a British precursor to Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale: Benefits, by Zoe Fairbairns. Published in 1979, the novel starts in the author’s contemporary world, before eventually moving through to a projected future in the late 1990s. It centres around Lynn Byers, who, in the 1970s, is a young, married journalist who feels ambivalent about having children and is interested in the Women’s Liberation Movement, but not actively involved. She and her husband live on Seyer Street, a Victorian slum in South London that really should be condemned, and at the end of the street is an abandoned Local Authority tower block of flats, Collindeane, which immediately after its building was deemed unfit to house people and so has been left to slowly rot, and is then taken over by a group of radical feminists as a commune. Lynn has no relationship with her neighbouring feminists until the government decides to stop paying women Child Benefit, which causes a great deal of feminist outrage, and so Lynn heads over to Collindeane to hear what the women have to say about it. While there, she meets Posy, the enigmatic Australian ringleader of the commune, and timid, impressionable Marsha, its well-to-do young financier, who has run away from her wealthy background and its expectations to live life on her own terms. Posy sees herself as the head of a new worldwide feminist revolution, but her desire to lead is at odds with the women’s opposition to hierarchical structures. She is in love with Marsha, but Marsha’s fear of leaving her boyfriend David, and a conventional life, is creating a great deal of tension between the women. Into the fray enters Lynn, keen to know and understand more about the women’s movement and how to bring about societal change.

Fast forward a few years, and the government has been taken over by the Family Party, who want to pay women to stay at home and look after their children and restrict them from working. Family First and a return to traditional values is touted as true freedom for women, who can devote their energies to the home, without having to worry about money. However, this payment, called Benefit, can be withdrawn if a woman is deemed not good enough at her work of motherhood – if she is a feminist, or a lesbian, if she refuses to have sex with her husband, leaves her husband, or tries to earn any money outside of the home, and if this happens, she has to go to a reeducation center in order to learn her true role and earn back her right to Benefit payments. As the book progresses, Family First’s policies become even more extreme, with enforced sterilisation of ‘undesirable’ women, the encouragement of people reporting on neighbours and friends who might be ‘undesirable’, increased removal of Benefit payments from ‘unsuitable’ mothers, and a corresponding plunge into mass austerity, as families struggle to make ends meet in a country whose economy has declined rapidly. When Marsha returns from a decade of traveling the world with Posy, spreading the message of feminism, to find her former boyfriend David in charge of sterilisation in the Family Party and a country in tatters, she decides that it’s time she stopped relying on everyone else to take action and did something herself. Rallying the women of Collindeane together, with the support of Lynn and her husband Derek, they start to mount a resistance. But how far are they willing to go to achieve change, and if they are successful, can they agree on what an equitable future would look like?

The story is far more complicated than this brief summary can explain, and I’ve left out various characters and details that would spoil the plot if I told you, but the overarching story of how quickly a government can take control of women’s rights, freedoms and reproductive choices is both compelling, and chilling. The blurb on the back compares it to an H.G.Wells novel in its dystopic vision, and I can see the comparison, but there is also much to compare with Atwood in its sensitive, complex and emotive exploration of women’s experiences, relationships and internal conflicts over their life choices. Lynn fears what motherhood would do to her intellectual life, her career, and her marriage and friendships, but she also has a genuine desire to be a mother and bring up a child, and in her thirties, she doesn’t have much time left to make a decision. If she does have a child, will she regret it as much as if she didn’t? Would the sacrifices she had to make be worth it? The fact that women still need to have these debates, forty years after this book was written, is a powerful indictment of how little progress really has been made for women in the 20th and 21st centuries. Derek, Lynn’s husband, doesn’t really have much to say about the matter, as he knows it won’t affect his life in the same way; after all, it will be Lynn juggling the childcare while still trying to have a life of her own, and we know from the statistics of how much childcare and housework women do compared to men, despite working full time outside of the home, that this is not a situation that has changed for many women. The feminist commune’s outrage at a male government making choices about women’s reproductive rights also feels depressingly contemporary; you only need to look at the debates surrounding access to abortion in America to know that this is still so many women’s daily reality in the so-called liberal Western world.

Benefits is a brilliantly written, incisive exploration of the complexities and absurdities of gender roles and expectations, and while it absolutely advocates the power of women to bring about change through collective action, it also sensitively and realistically depicts how difficult it can be to have a collective movement when everyone’s experiences of being a woman are very different. It also has much to say about the challenges of social economic policies and of juggling support of the vulnerable without incentivising irresponsible behaviour; David, Marsha’s former boyfriend, is a fascinating character in this respect. While it is a little dated in places, it really doesn’t feel forty years old, and I loved every minute. It gave me so much to think about, and I really can’t understand why it hasn’t become a more foundational feminist literary text. It’s easily on a par with The Handmaid’s Tale, and would be an excellent comparative text to teach alongside it. I’m going to be recommending this to everyone; it’s still in print, though no longer by Virago (I wonder why not?) and I really encourage you to read it. I’m so excited to have found Zoe Fairbairns’ writing, and I can’t wait to read more of her work!