Indiana Jones would have loved it: 65,000 years ago, stone age hunters in Africa gathered at night in a hidden cave to worship the giant rock snake that seemed to move in the flickering firelight and hissingly promised fertility so long as the rituals were performed. They came to this place every year during when the surrounding desert was dead or dying. The plants were withered, game scarce, and water precious. The Snake God promised rain and renewal, but only if it was fed. The faithful crafted beautiful and rare hunting darts in the presence of the god, and then sacrificed the points by burning and smashing them. The snake spirit was placated and the rains came.

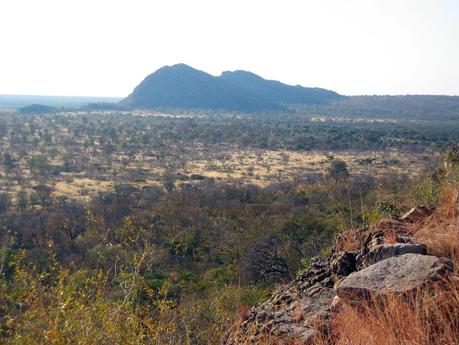

This was the scene that, since 2006, many have imagined was played out in the Tsodilo Hills of northern Botswana during a critical time in human history. It is about this time, the Middle Stone Age of Africa, when we begin seeing the earliest evidence of symbolic thought and modern behavior in the archaeological record. Surrounded for many miles by the flat and featureless Kalahari, the Tsodilo Hills rise unexpectedly and have been attracting humans for tens of thousands of years.

The San or Bushmen who consider this area home have been coming here for hundreds and perhaps thousands of years. It is for them a special and supernatural place, and is known to visitors as “Mountain of the Gods.”

Those who were looking forward to confirmation of this sensational story by Sheila Coulson, the Norwegian anthropologist who (inadvertently) turned the world’s attention to “Python” or Rhino Cave in 2006, are bound to be disappointed by her recently published study, “Ritualized Behavior in the Middle Stone Age: Evidence from Rhino Cave, Tsodilo Hills, Botswana” (open access). Coulson and colleagues present their finds in considerable detail and conclude that ritual activities did in fact take place in Rhino Cave during the Middle Stone Age, but there is no mention of worship, religion, shamans, or a “snake god.” While this is bound to disappoint some, it makes for good archaeology.

The authors’ primary argument is that “Rhino Cave was a site with unusual behavioral patterns involving the manufacture and abandonment or intentional destruction of artifacts….Once complete, these [MSA] tools, which are normally associated with hunting or butchering, never left the cave. Instead, they were burnt (along with their waste debitage), abandoned, or intentionally broken.” If this indeed the case, the authors are surely correct this is evidence for ritualized behavior. Coulson is appropriately cautious about saying more, though she suggests these could have been acts of “sacrifice” and the unusual rock formation (i.e., the “snake” or “turtle”) may have played a role.

It will be interesting to see how this plays out. The biggest problem at the moment is that these finds remain undated. Archaeologists who have previously worked the site and others will surely comment. Back in 2006, Julien Riel-Salvatore commented on Coulson’s preliminary results and raised several questions the current study does not appear to address. It addresses many others, however, and Coulson and colleagues deserve praise for their careful and thorough analysis.

In the meantime, Coulson’s study should put to rest the fanciful idea that Rhino or “Python” Cave provides evidence for the “world’s oldest religion.” While it is clear that something interesting and perhaps unusual was happening at Rhino Cave, we don’t know exactly when or in the service of what. Stay tuned for the rest of the story.

Reference:

Coulson, Sheila, Staurset, Sigrid, & Walker, Nick (2011). Ritualized Behavior in the Middle Stone Age: Evidence from Rhino Cave, Tsodilo Hills, Botswana PaleoAnthropology, 18-61 : 10.4207/PA.2011.ART42