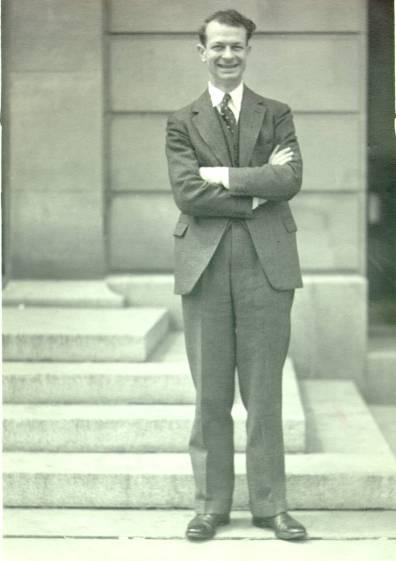

Linus Pauling, 1936.

[Pauling as Administrator]

In mid-July 1936, Pauling received a thought-provoking letter from Christopher Kelk Ingold of University College London. In it, Ingold wondered if Pauling might be tempted to replace F. G. Donnan as chair of the university’s Department of Chemistry. For Ingold, this was a bit of a fishing expedition and he made it plain that he did not really expect Pauling to take the idea seriously.

As such, it likely came as a surprise when Ingold received Pauling’s response a month later. In his reply, Pauling revealed that he had been devoting a great deal of thought to the offer and divulged his motivations for doing so, writing

In general I have been in the past very well pleased with my opportunities here for teaching and carrying on research. Subsequent to the death of Professor Noyes, however, the affairs of our Chemistry Division have been in some confusion, and the problem of administration has not yet been solved.

Pauling also relayed his intrigue at the possibility of working with Donnan and living in in such a radically different location.

Though adjusting to life in England would surely be difficult for Pauling and his family, the challenge of doing so did not appear to be an issue of pressing concern. Rather, the only major obstacle impeding Pauling’s acceptance of the offer was its base salary of £1,200 per year, which he calculated to be less than his current Caltech salary of $6,300. Pauling also discerned that the taxes on his University College earnings would amount to £360, which was about $1,000 more per year than what he was paying in California.

Pauling communicated his concerns about the proposed salary package to Ingold, perhaps hoping that University College would reply with a counter. Instead, Ingold merely repeated the offer while reiterating his sense that it might not be enough to attract a talent of Pauling’s magnitude.

In his reply, Pauling took up their correspondence on chemical matters, but also described how the experience of meeting biophysicist Archibald Hill, who was visiting Pasadena, had made him “realize more keenly than before” that he would not miss coming to London. The courtship had reached its conclusion.

Not long after declining the University College offer, Pauling was similarly recruited for a one-year stint at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, and also for the George Fischer Baker Lectureship, a six-month visiting appointment offered by Cornell University’s Department of Chemistry. While neither of these opportunities would have taken him away from Caltech permanently, they did serve the important function of demonstrating to Pauling that he had reached a new level of stature within the profession.

Pauling’s first inclination was to choose the Baker Lectureship, though he made inquiries at Caltech to determine whether or not he could receive enough leave to fill both visiting positions. Ultimately he was extended only one semester’s worth of paid leave and so chose Cornell.

In weighing his leave options, Pauling had consulted with Robert Millikan, the chair of Caltech’s Executive Council. Millikan was pleased with the decision that Pauling made and, as a byproduct of their recent conversations, once again broached the idea of Pauling moving in to the position of division chair.

With several months having now passed, Millikan specifically asked if Pauling might still have the “desire to suggest changes in the organization of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering such as would make your continued association with and leadership of that Division satisfactory to you.” With plans for the new Crellin Laboratory finally set and construction soon to begin, resolving the question of division leadership was becoming more and more important.

Noting that Millikan was open to negotiation and sensing that he had the upper hand, Pauling waited for the new year, 1937, to respond. In doing so, Pauling made it clear that the changes that he would desire remained consistent with the suggestions the suggestions that he had put forth in his letter to the Executive Council of November 1935. Pauling also communicated his willingness to directly discuss the points he had made in his August letter with the Executive Council. As it turned out, Millikan had never forwarded Pauling’s letter to the Executive Council, so a discussion of this sort would prove essential to satisfying Pauling’s demands.

Around this time, Warren Weaver of the Rockefeller Foundation, who had favored Pauling as division chair from the start, came to Pasadena to help mediate the situation. Weaver chose to interject himself in part because Millikan, who had little interest in biochemical research, had taken over management of the potential Rockefeller grant that had been worked out with A.A. Noyes prior to Noyes’ death.

While in Pasadena, Weaver met with Pauling and listened to his concerns over the lack of power invested in the chair under the stipulations put forth by the Executive Council in Fall 1935. Pauling also discussed with Weaver his salary ambitions and desire for an appropriate title. Using the sway that he had accumulated as a major source of funding for the division, Weaver then began negotiating on Pauling’s half. It did not take long for Pauling’s salary to be increased to $9,000 in addition to the title of Chairman of the Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering and Director of the Chemical Laboratories. It would still take several months however, before all of the details were worked out.

As Pauling and Millikan mended fences, Pauling began thinking in concrete terms about the future of the division. In mid-March 1937, he wrote a note to himself about the unit’s financial future which, in the midst of the Depression, depended heavily on the Rockefeller Foundation. Be it by choice or necessity, it is clear that Pauling was on board with the foundation’s involvement, writing that it “would help the Division as a whole both scientifically and financially.”

By now, the foundation’s influence on division affairs had become increasingly evident. One particular instance involved the hiring of Carl Niemann, a biochemist working at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, who was brought on to help staff the brand new Crellin Laboratory. At Weaver’s urging, Niemann was invited to visit Pasadena with the understanding that he would be offered a $3,000 assistant professorship starting that September. This despite the fact that Niemann was obligated to remain in Zurich until the following year.

On April 14, 1937, Millikan conveyed to Pauling that it had been informally agreed upon by the Executive Council that Pauling’s salary would increase to $9,000 in 1938 and that he would receive the title of division chair at the next Executive Council meeting. In his documentation of that conversation, Pauling wrote that

Professor Millikan intimated that I might desire the action to be postponed a little beyond that time in case that [historian William Bennett] Munro and [physicist Richard] Tolman could not be raised simultaneously to $9000 from $8100, and I replied that I preferred a definite understanding in order that I might incur certain obligations.

At a meeting of the Division Council, held on April 23, Pauling was recognized for the first time as chair, and on May 4 he was informed that the Executive Council had officially approved his appointment. By mid-August 1937, all agreements had been formalized and approved by the Board of Trustees. At long last, Pauling was finally chair.