*******

So You work in a Cotton Mill ... by Chrissie Elmore

‘So you work in a cotton mill? Now don’t you complain about getting up at 5am. In 1851 with everyone flooding into Manchester for jobs and starving Irish undercutting the wages, you’re the lucky one. At least it means your family has a roof over their heads.

I know running home for a cup of tea and piece of bread at 8am hardly seems worth it when you only have half an hour but at least it will keep you going until 12, then you can share a nice bowl of potatoes with those tiny pieces of bacon fat. Yes, it’s boring when you’ll get exactly the same for supper when you’re shift ends at 8pm, but let’s face it, your Ma wouldn’t know what to do with anything else if she could afford it – she went into the factory when she was six.

Oh, and try and use the privy at the mill – you don’t want to go near the one in the corner of the court that hasn’t been cleared for months.’

Yep, there was a very fortunate girl: a wage coming in (never mind that the Master had reduced it twice due to ‘market forces’); a house less crowded than the one next door where Michael Norton shared two rooms with his six children, mother-in-law, elderly lodger and her son, to say nothing of the Flahertys and their 5 children in the cellar.

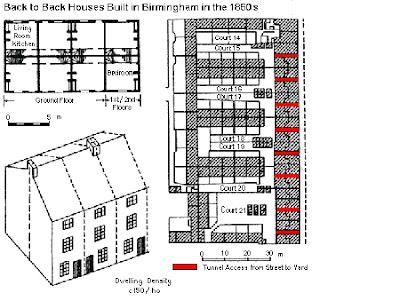

The house would have been single brick skin, sodden in wet weather, and with only one window – being built against on three sides. These back-to-back terraced houses had no water or sanitation. The privy would be shared by the whole community (at worst up to 250 people – no typing mistake – 250!). With no drainage, the cellars were built to take storm water and the effluent from the tons of household rubbish thrown into the yard plus the run-off from the privy. Desperate people rented these hellholes and many drowned in their sleep. (See diagram of some quite posh back-to-backs in Birmingham)

"In one of these courts there stands directly at the

entrance, at the end of the covered passage, a privy without a door, so dirty

that the inhabitants can pass into and out of the court only by passing through

foul pools of stagnant urine and excrement.”

Description of hovels in Condition of the Working Classes in England

in 1844. by Fredrich Engels (1820-95) who spent much of his working life in

his father’s Manchester cotton mill.

"In one of these courts there stands directly at the

entrance, at the end of the covered passage, a privy without a door, so dirty

that the inhabitants can pass into and out of the court only by passing through

foul pools of stagnant urine and excrement.”

Description of hovels in Condition of the Working Classes in England

in 1844. by Fredrich Engels (1820-95) who spent much of his working life in

his father’s Manchester cotton mill.

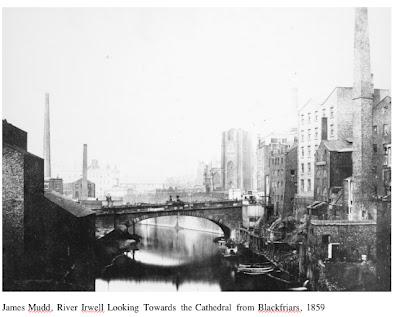

Manchester’s River Irwell into which all manner of industries emptied their waste from tanning factories to slaughter houses and from which many people drew their only water.

Not surprising then that our girl had an average life expectancy of 26 (17 if she was a man). If the dysentery or TB didn’t get you, then cholera probably would. One outbreak resulted in a pit of 40,000 bodies. Not much later the bones were dug up to sell for manure, bone meal or to adulterate flour. Even if you survived beyond this age, as a girl working in a cotton mill, especially in the carding room, you would suffer for years with lung disease.

Many brave, dedicated people tried to improve things and laws were eventually passed:- 1866 The Sanitary Act (sewage disposal and water supply provision); 1870 Education Act (full time education until 9); 1891 Factory and Workshop Act (minimum employment age 11) but enforcement was patchy and there were many vested interests to overcome.

Fact becomes Fiction

In Mrs Gaskell’s novel North

& South, these issues form an important part of the narrative –

shocking Margaret and causing conflict between her and Thornton.

Mrs Gaskell lived in

Manchester from her marriage onwards and all her books are coloured by the

people she met and the conditions she saw first hand. I tried to continue this

fine example when writing Unmapped Country therefore it contains many issues of the day: industry, social

conventions, disease, plus one or two real characters of the time (Edmund

Potter, calico printer and MP, for example).

In Mrs Gaskell’s novel North

& South, these issues form an important part of the narrative –

shocking Margaret and causing conflict between her and Thornton.

Mrs Gaskell lived in

Manchester from her marriage onwards and all her books are coloured by the

people she met and the conditions she saw first hand. I tried to continue this

fine example when writing Unmapped Country therefore it contains many issues of the day: industry, social

conventions, disease, plus one or two real characters of the time (Edmund

Potter, calico printer and MP, for example).

Unmapped Country is available on Kindle - it’s not all Mills & Gloom, as a friend rudely puts it!

Chrissie Elmore

The book

Think of Manchester in the mid Nineteenth century and mention Margaret Hale & John Thornton to people and many will immediately tell you how they fell in love with North & South by Elizabeth Gaskell. For them this will be an extension of the extreme pleasure they had first time round.

However, readers unfamiliar with this enduring classic, need not turn away. The novel stands alone and only entices them to discover the back-story. As the author has discarded Mrs Gaskell’s much disliked ending (even by herself), John and Margaret’s struggles continues. Will they ever truly understand one another? Or will their opposing ethics and social prejudice force them to seek companionship with more appropriate partners? Written in the original’s Victorian style, the frenetic city and the original participants all stay true to Mrs Gaskell’s creation, while contemporary events and new characters both help and hinder John and Margaret’s progress towards a conclusion.

The author

Born in the north of the UK, five glorious years in New

Zealand but now an adopted southerner living on the edge of the Ashdown Forest

(home of Winnie the Pooh) in Sussex. After a varied career – secretary,

florist, bar tender, quantity surveyor - Chrissie Elmore finally found her feet in managing

brochure production for travel companies.

Born in the north of the UK, five glorious years in New

Zealand but now an adopted southerner living on the edge of the Ashdown Forest

(home of Winnie the Pooh) in Sussex. After a varied career – secretary,

florist, bar tender, quantity surveyor - Chrissie Elmore finally found her feet in managing

brochure production for travel companies.

Leaving corporate-land, going freelance and departing from husband number two, gave her the opportunity to write and three novels later she can say that the thrill of giving birth to stories is still as strong now as it was when making up tales for her ten-year-old cousin all those years ago.

Chrissie Elmore's website also has loads more fascinating details of the mid -Victorian era and news of her second book which is set in the same period.