When I was asked if I'd be interested in reviewing a CD with the tantalizing title At the Statue of Venus, my response was, approximately, "Would I!" The album showcases the dynamic soprano Talise Trevigne, who sings the music of Jake Heggie and Glen Roven. It's titled after Heggie's scene for soprano and piano, to a text by Terrence McNally, but also features a song cycle by each of the composers, who play the piano parts of their respective works. To me, both Trevigne's name and voice were new, and the latter was the most exciting discovery of the album, supple and expressive across her range. I found Trevigne to be a very emotionally engaging communicator, using varieties of vocal color, and nuanced phrasing, which drew me into the worlds of unfamiliar music and texts. The album was a pleasure on first and repeated listenings, and is recommended especially to those among you, Gentle Readers, who are lovers of art song or sopranos.

When I was asked if I'd be interested in reviewing a CD with the tantalizing title At the Statue of Venus, my response was, approximately, "Would I!" The album showcases the dynamic soprano Talise Trevigne, who sings the music of Jake Heggie and Glen Roven. It's titled after Heggie's scene for soprano and piano, to a text by Terrence McNally, but also features a song cycle by each of the composers, who play the piano parts of their respective works. To me, both Trevigne's name and voice were new, and the latter was the most exciting discovery of the album, supple and expressive across her range. I found Trevigne to be a very emotionally engaging communicator, using varieties of vocal color, and nuanced phrasing, which drew me into the worlds of unfamiliar music and texts. The album was a pleasure on first and repeated listenings, and is recommended especially to those among you, Gentle Readers, who are lovers of art song or sopranos.The first cycle on the disc, Heggie's Natural Selection, is exuberant in musical invention and allusion. The trajectory of the cycle is tragicomic, condensing the matter for a Bildungsroman into five songs. The persona journeys from confidence on the threshold of adulthood ("Creation,") through fiercely passionate, though still abstract desire ("Animal Passion," a sly, dark tango,) to feverish discontentment ("Alas! Alack!") to "Indian Summer," the lament of a woman trapped in marriage for lost freedom, which is recovered at last in "Joy Alone." The discordant, jumpy anxiety of "Alas! Alack!" is packed with operatic allusion (what would happen if Tosca fell for Scarpia?) which continues in the ragtime, Bluebeard-referencing "Indian Summer." The voice of the piano, helping to illustrate the narrator's emotional state, reinforces the rightness of where we leave her: the style of the first song has been recovered, altered, but at peace and ready for new journeys.

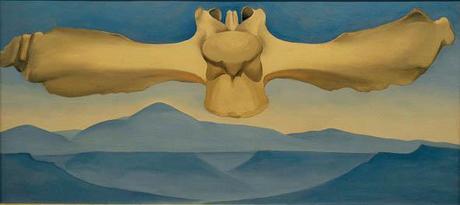

Flying Backbone, Georgia O'Keefe

Glen Roven's Sante Fe Songs carry with them some of the atmosphere of surreality which the composer describes as enveloping his first visit to Santa Fe, following a personal loss. Some time later came the selection and setting of texts; the finished cycle explores simultaneously the landscapes of the city and of grief. The poems ("Spring, 1948," "Listening to jazz now," "Signs and Portents," "The Boy Soldier," "Bowl," "Flying Backbone," "Bone Bead," "Sowing the Pecos Wilderness") are all strong in their own right, and the musical settings let the texts shine, syllables blooming into melismatic significance. Roven also uses silence eloquently, notably in "The Boy Soldier" and "Flying Backbone." Elsewhere, denser musical textures recall other compositions, with Porter and Gershwin invoked in "Listening to jazz now,"and reminiscences of "La cathédrale engloutie" in the final song. Defiance and bafflement are coaxed into expression, not fully resolved, but given beauty.

Image (c) Malissin/Valdes, via photos-galeries.com

After so much suffering, it's a relief to come into the presence of Rose, a lively, self-amused, generous woman waiting for a blind date in the Louvre. Terrence McNally's libretto is witty and insightful, allowing us to laugh with Rose as she frets and mocks her own anxiety, and to admire her self-knowledge, compassion and--to use an old-fashioned word--wholesomeness. (There is, in "Look at all those women," some idealization of the idealization of women which I found irksome despite its seductions.) The text is rich, but it's the music which gives it emotional specificity, telling us when Rose is irritated, dreamy, or optimistic. Despite the black slacks which she regrets wearing, Rose's agitated vigil gets a hopeful conclusion.