Ewan Cameron, Ava Helen and Linus Pauling. Glasgow, Scotland, October 1976.

[Ed Note: Today’s post is the first installment of a two-part look at Linus Pauling, Ewan Cameron and Brian Leibovitz’ extensive 1979 review of the published literature pertaining to research on ascorbic acid and cancer.]

Students of Linus Pauling’s life will know full-well that Pauling expended significant energy over his latter decades advocating for the use of ascorbic acid, or Vitamin C, in the treatment of cancer. One of his lengthier research endeavors, and certainly among his most controversial, Pauling’s interest in and advocacy of ascorbic acid therapy prompted a wide array of responses from scientists, journalists, and patients, among many others.

Pauling’s views also attracted the disdain of most medical professionals. One notable exception to this theme was Ewan Cameron, a Scottish surgeon who became so invested in the work that he eventually relocated to California to join the staff of the Linus Pauling Institute of Science and Medicine.

Prior to his immigration, Cameron had shared a rich correspondence with Pauling through which the colleagues bounced ideas off one another and even co-wrote papers. Cameron, who was head of his department at the Vale of Leven Hospital in Alexandria, was permitted to run a clinical trial testing the efficacy of ascorbic acid treatments on terminal cancer patients. He then relayed his data to Pauling, who studied the Alexandria results and contributed his thoughts on the chemical mechanisms that might be underlying them.

In 1979, Pauling, Cameron and a third author published a major literature survey titled “Ascorbic Acid and Cancer: A Review.” Appearing in the March 1979 edition of Cancer Research, the paper marked a crescendo of the duo’s eight years of work in the cancer field; work which they attempted to bolster using all of the previous and ongoing studies that they could find.

The survey, which took up ten journal pages and included 358 references, was published with the hope that it might serve to counter some of the skepticism that its authors were encountering, while also inspiring new researchers to turn their own attentions toward the potential benefits of ascorbic acid. As was typical during this period of Pauling’s career, the reception that the paper received was mixed at best.

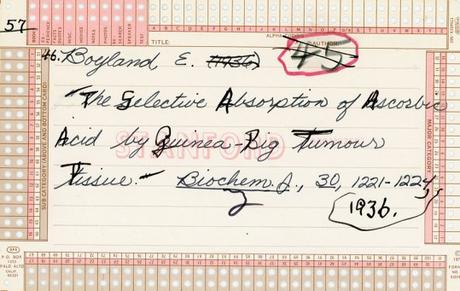

One of the 1,000+ references gathered by Brian Leibovitz for use in “Ascorbic Acid and Cancer: A Review.”

Pauling and Cameron first began toying with the idea of a grand literature review in 1976. Having struggled mightily with both the medical community and mainstream publishers for five years, the duo had, by 1976, finally managed to get a few papers into print. Encouraged by these successes, the co-authors agreed that gathering all available research on Vitamin C and cancer, and presenting it in one paper, would make for a very useful contribution to a decidedly nascent field.

There was a secondary ambition in play as well. Though brimming with ideas, the resources available to the two scientists were scarce and, as a result, they had arrived at an impasse of sorts. Lying at the heart of the matter was the fact that basically all of the leading medical journals had refused to publish the clinical work that Cameron and Pauling had conducted, because they hadn’t been able to follow a proper double-blind study protocol. Instead, Cameron had matched his ascorbic acid patients – by age, sex, and cancer type -with previous patients who had been treated at the Vale of Levin hospital but hadn’t received ascorbic acid.

Likewise, Cameron believed so strongly in the benefits of ascorbic acid that he refused to withhold it from incoming cancer patients who might otherwise populate a control group for his study. In his correspondence with Pauling, Cameron confided that to withhold ascorbic acid treatment from sick patients would stand as a violation of the Hippocratic Oath.

(Oddly enough, Dr. Thomas Addis – the doctor whose conservative therapies saved Pauling from an almost certain death sentence when he was diagnosed with glomerulonephritis in the 1940s – argued against the use of ascorbic acid for exactly the same reason. To discontinue traditional methods of cancer treatment he believed to be effective came at the cost of his patients, and Addis refused to do it.)

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York had conducted its own trial in 1974, but Cameron and Pauling suspected that there were problems with the scientific design of that study as well. Preventing this from happening again, especially as Pauling and Cameron were gaining increased attention from the medical community, was another motivation for publishing the review. Finally, the research that they had gathered also helped the co-authors in preparing a new book, Cancer and Vitamin C, which came out in 1979, only a few months after the review was published.

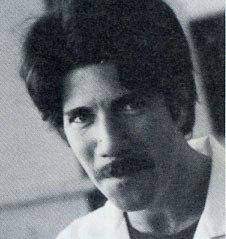

Brian Leibovitz

In putting together their article, Pauling and Cameron enlisted the additional help of Brian Leibovitz, a graduate student at Stanford who had worked at LPISM from 1975 to 1977. Leibovitz’ main task was straightforward: obtain reprints of anything related to ascorbic acid and cancer. Pauling also requested that Leibovitz look into other papers that focused on the environment shared by cells, as he and Cameron both believed that the intercellular environment held important – if, as yet, undiscovered – resources for treating cancer.

Leibovitz expressed great dedication to the multi-year project, continuing to collect references even after finishing up at LPISM and moving to Oregon. In the end, Leibovitz gathered over a thousand sources; for his work, his name appeared on the review as a third co-author.

Once it had been completed, Pauling encountered trouble finding a home for the review. Originally a friend had offered to have it published in Cancer Research, but upon seeing the manuscript, the editor complained that the paper was much too long. In response, Cameron worked on shortening the text while Pauling looked into other avenues for publication, including The Journal of Preventative Medicine and Cancer Reviews.

While Cancer Reviews was kind enough to respond that they were not interested in publishing anything on ascorbic acid, The Journal of Preventative Medicine did not reply at all. Just as the authors were about to give up, the editor of Cancer Research got back in touch, suggesting a series of changes and promising to publish the survey once it met with the requirements that he had outlined.

Advertisements &b; &b;