Are babies really more competent than we give them credit? (No.)

Developmental psychology is filled with studies that claim to show the hidden abilities of babies. The claim is that babies come pre-packaged with all kinds of knowledge and skills that provides them with the foot in the door they need to learn about the world. Babies are limited in their ability to demonstrate this knowledge, however, because of their immature bodies and inability to control these well. In the language of the field, there is hidden competence concealed by problems with performance, and researchers (such as Liz Spelke and Renee Baillargeon) are interested in finding ways to reveal this hidden competence.At IU we referred to such studies as 'super baby' studies, because they purported to show that infants were remarkably competent and knowledgeable about the world. Besides the rampant dualism of 'mind' being concealed by 'body', these studies are good examples of a common problem (the psychologist's fallacy) in psychological research, one that a rigorous application of embodied cognition helps fix.

The problem for these studies is that babies can't respond easily with actions. The classic method to address this is to use the one skill infants do have - looking at things. There are two common measures, preferential looking and habituation. The logic of preferential looking is that babies prefer to look at novel things and so will look longer at things that are different. (Except when the paper assumes that babies like looking at familiar things; I've seen this measure go both ways, a hint that no one's quite sure what's going on.)

The second measure, habituation, is more common. Infants are drawn to novelty and will look at things they find interesting; they will eventually get bored and move on, or habituate to the display. Their looking will perk back up if you give them something new to look at. The suggestion is that this provides a measure of whether an infant can tell the difference between two stimuli or events. If the difference is, say, whether the events are physically possible or impossible, and if the infant can tell the difference as shown by looking times, then presumably the infant knows something about what is physically impossible: they have some knowledge of physics.

This research is a classic example of the psychologist's fallacy. This is the error William James described like this:

The great snare of the psychologist is the confusion of his own standpoint with that of the mental fact about which he is making his report. I shall hereafter call this the ‘psychologist's fallacy’ par excellence.In essence, the problem is running an experiment in which you label a variable in terms of, say, physical possibility vs. impossibility. You then find a difference in behavior as a function of that manipulation, and conclude that physical possibility was the critical difference. This is an error when there are simpler explanations, such as perceptual differences in the stimuli (different length trials, different amounts of things in the displays, etc) which might account for your data.

William James, Principles of Psychology volume I. chapter vii. p. 196, 1890

Habituation work is one of the biggest offenders of this fallacy; babies indeed dishabituate to the displays but dishabituation only means babies could detect a difference. What dimension that difference is on requires more careful analysis than is typically done here. Experiments do generally include various control conditions that attempt to make sure that it's the physical impossibility driving the change in looking behavior but these are typically quite weak and not grounded in a theory of perception.

Habituation and information

Habituation is about perception. Babies will habituate when the informational content of the display hasn't changed in a while, and they will resume looking when they detect that the content has changed. Psychologists using this method usually define information in terms of things like physical possibility, or causal relations. All their experimental manipulations are at this level, and the lower level details are ignored (or superficially controlled for). I do know of one paper that examined habituation using carefully controlled visual events, however, and the results are illuminating.

Wickelgren & Bingham (2001) looked at infant sensitivity to trajectory forms. These are the perceptual structure underpinning event perception, where an event is the unfolding of a particular dynamic over space and time. For example, a pendulum swing is an example of a simple dynamical system, and it's behavior over time is described by a simple equation of motion. The equation is of the underlying dynamic, and the event is the kinematic path traced out as that underlying dynamic happens.

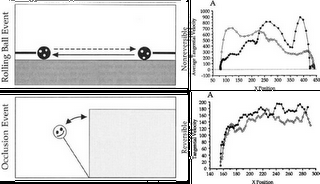

Wickelgren & Bingham showed 8 month old infants displays made from one of three event types, each with a different underlying dynamic. Infants were either habituated to the event running forwards or backwards in time. The first was a rolling ball; the ball was pushed and accelerated to a peak speed, then slowed down under the influence of friction. The spatial path is the same run forwards or backwards, but the dynamics underlying the motion are not. The second was a toy moving behind an occluder; this event is symmetrical and the underlying dynamics do not change when run in reverse. The third was a splash event; here neither the spatial nor the motion characteristics of the event were symmetrical in time.

Figure 1 shows the ball and occlusion events and the associated velocity profiles (kinematic trajectory forms) for the event running forwards (filled markers) and backwards (open markers) in time. Note that the ball trajectory form is not symmetrical in time; this means that running the ball event backwards is incorrect according to the underlying dynamic and produces a different trajectory form. The occlusion trajectory form is symmetric in time, however; running an occlusion event backwards is perfectly legitimate and the trajectory form is the same.

Figure 1. Events and the associated trajectory forms from Wicklegren & Bingham (2001).

The results were straight forward; infants habituated to the display they saw (the event running either forwards or backwards in time) and then dishabituated to the other version if there was a difference in the trajectory form (large dishabituation to the ball event, small but significant dishabituation to the splash event, no dishabituation to the not-different occlusion event). They could tell the difference between the two versions and were thus demonstrating they are sensitive to the differences in the kinematic trajectory forms. However, there was no difference in rate of habituation or looking times to initially looking at the forwards vs backwards event; infants showed no preference for the 'correct' event, thus demonstrating that they didn't know anything about the underlying dynamics causing the event structure.You could have defined the displays as 'forwards' and 'backwards' in time and come to the conclusion that infants understand the difference in those terms; but this is the psychologist's fallacy. Wickelgren & Bingham took a first person perspective and analysed their results with respect to what the infants actually experienced, namely a trajectory form caused by an underlying dynamic, and showed infant sensitivity to the former but not the latter. Adults, of course, have learned the underlying dynamic; the reversed events look wrong (except the occlusion event, where reversing is perfectly possible). Infants come able to distinguish the event structure, but knowing what the event structure means (specifies) requires learning.

Habituation is a dynamical process

The real problem with using habituation is that it is a process with it's own dynamical properties that are poorly understood. The assumption that this process is a nice, straightforward linear one, where looking times simply decrease as a function of familiarity and nothing else matters is, unfortunately, entirely incorrect.

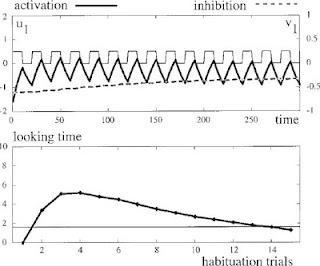

Just before she died, Esther Thelen had begun working on a dynamical system model of the process of infant habituation, looking to see how the process unfolded over time without making assumptions about the content of the displays (Schöner & Thelen, 2006). The basic dynamic being modelled (Figure 2) contains both activation and inhibition running alongside one another at slightly different timescales.Whenever the stimulus is presented it provides a positive input to the model that lasts the duration of the stimulus; over time and repeated presentations, inhibition in the system simply increases. These combine to produce the overt behaviour, looking time.

Figure 2. The basic dynamics of infant habituation from Schöner & Thelen, 2006

The model allowed Esther to systematically vary experimental and infant characteristics and look to see what happened to looking times. Everything they looked at made big differences; the timing between trials, the strength of the stimulus, and, more interestingly, characteristics of the infant such as the intrinsic rate of habituation. These all interacted non-linearly to produce radically varying looking time behavior. Schöner & Thelen then used the model to simulate Baillargeon's classic 'drawbridge' experiment (Baillargeon, Spelke & Wasserman, 1985) and replicated many key phenomena (including the known effects of stimulus order, and variation in looking preference for fast vs slow habituators, etc). The model contains no knowledge of physics; it is merely activated and inhibited as a function of the amount and timing of information and the preferred rate of habituation.Conclusion

The point, as ever, is that the overt behavior being measured (looking time) actually emerges from the underlying dynamics of the task at hand, and whether those dynamics include 'knowledge of physics' requires careful analysis. The model work suggests that this knowledge is not necessary to explain the looking behaviour, and thus the claims of extraordinary knowledge are not supported by the data.

Avoiding the psychologist's fallacy is hard work, but all that's really required is a first person perspective on the problem. As in embodied cognition, the important questions are about what the task looks like to the observer, not the psychologist, and it is an empirical question as to which task resources are used to solve the problem at hand.

So is there a performance-competence distinction? Are babies really super, with hidden abilities revealed by careful experimentation? Probably not. Babies are embodied dynamical cognitive systems, burbling along in a sea of information they are set up to detect and discriminate but not fully understand without learning. So while cute, and definitely active perceiver-actors, babies aren't really super.

Except ours. Our baby is awesome :)

References

Baillargeon, R., Spelke, E., & Wasserman, S. (1985). Object permanence in 5-month old infants. Cognition, 20, 191-208.

Schöner, G., & Thelen, E. (2006). Using dynamic field theory to rethink infant habituation. Psychological Review, 113 (2), 273-299 DOI: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.2.273 Download

Spelke, E. S., Breinlinger, K., Macomber, J., & Jacobson, K. (1992). Origins of knowledge. Psychological Review, 99, 605–632.

Wickelgren, E., & Bingham, G. (2001). Infant sensitivity to trajectory forms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 27 (4), 942-952 DOI: 10.1037//0096-1523.27.4.942 Download