It’s here.

The antibiotic-resistant superbug dubbed “nightmare bacteria” is now a fact of life in the United States.

A year ago, PBS’s Frontline reported that the largest U.S. outbreak on record of a strain of “nightmare bacteria” that infected 44 people at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in suburban Chicago “is fueling alarm among public health officials about the spread of potentially lethal drug-resistant infections.” At the time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said just 96 cases of the infection had been reported to the agency since 2009.

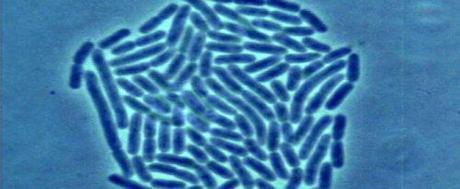

The bacteria strain, known as carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE), is a form of superbug that lives in the gut and can carry a gene called NDM-1 that is resistant to practically all antibiotics on the market today. Perhaps more alarming, the gene can jump from bacteria to bacteria, making treatable infections untreatable.

Since the Chicago infection, the superbug has leapt across the continent to the west coast.

Chad Terhune reports for the Los Angeles Times, Feb. 18, 2015, that nearly 180 patients at UCLA’s Ronald Reagan Medical Center may have been exposed to the CRE “nightmare bacteria” from contaminated medical scopes, and two deaths have already been linked to the outbreak. UCLA declined to provide details on the two people who died, citing patient confidentiality. The number of CRE-infected patients may grow as more patients get tested.

UCLA said it discovered the outbreak late last month while running tests on a patient. This week, it began to notify 179 other patients who were treated from October to January and offer them medical tests. By some estimates, if the infection spreads to a person’s bloodstream, the bacteria can kill 40% to 50% of patients.

At issue is a specialized endoscope inserted down the throats of about 500,000 patients annually to treat cancers, gallstones and other ailments of the digestive system, in a procedure called ERCP or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. These duodenoscopes are considered minimally invasive, and doctors credit them for saving lives through early detection and treatment.

But medical experts say some scopes can be difficult to disinfect through conventional cleaning because of their design, so bacteria are transmitted from patient to patient. The duodenoscopes typically involved in the CRE outbreaks have an “elevator channel” that doctors use to bend the device in tight spaces and allow for attachments such as catheters or guide wires. Experts suspect bacteria build up in that small area.

But Dr. Alex Kallen, an epidemiologist in CDC’s Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion, said he hasn’t found any breaches in cleaning protocol at hospital outbreaks he has investigated. He believes the problem probably is more complicated than just a design issue: “There isn’t an obviously easy solution to employ. There is action on a lot of different fronts.”

The duodenoscopes are not the same type used in more routine endoscopies and colonoscopies.

UCLA said it immediately notified public health authorities after discovering the CRE bacteria in one patient and tracing the problem to two of the duodenoscopes. Dale Tate, a university spokeswoman, said UCLA had been cleaning the scopes “according to standards stipulated by the manufacturer.” After the infections were discovered, “the two scopes involved with the infection were immediately removed and UCLA is now utilizing a decontamination process that goes above and beyond the manufacturer and national standards.”

The UCLA outbreak is the latest in a string of similar incidents across the country that has top health officials scrambling for a solution. State and federal officials are looking into the situation at UCLA as they wrestle with how to respond to the problem industrywide.

Since 2012, there have been about a half-dozen outbreaks affecting up to 150 patients in Illinois, Pennsylvania and most recently at a well-known Seattle medical center, according to experts. These outbreaks are raising questions about whether hospitals, medical-device companies and regulators are doing enough to protect patient safety. Some consumer advocates are also calling for greater disclosure to patients of the increased risks for infection before undergoing these procedures.

Lawrence Muscarella, a hospital-safety consultant and expert on endoscopes in Montgomeryville, Pa., said the recent number of cases is unprecedented: “These outbreaks at UCLA and other hospitals could collectively be the most significant instance of disease transmission ever linked to a contaminated reusable medical instrument.”

CDC officials said they were assisting the L.A. County Department of Public Health in its investigation of the UCLA infections. Dr. Alex Kallen said the outbreaks are serious given the high mortality rate of this superbug and how difficult it can be to treat. He warns that additional cases might be going undetected.

Last month, Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMMC) in Seattle acknowledged that 32 patients were sickened by contaminated endoscopes from 2012 to 2014 with a bacterial strain similar to CRE. Eleven of those patients died. But VMMC said other factors may have contributed to their deaths because many of the patients were already critically ill. VMMC instituted a new quarantine process that sets the endoscopes aside for 48 hours so evidence of any bacterial growth can be found before reusing them. That has increased the time for equipment cleaning from a couple of hours to more than two days. VMMC said it had to purchase 20 additional endoscopes to compensate for that down time.

“There is either a design issue to be addressed or a change to the guidelines for the cleaning process,” said Dr. Andrew Ross, section chief of gastroenterology at VMMC. “It’s the role of the federal government to make some of those decisions.” Some patient-safety advocates say FDA regulators and industry officials have been too slow to respond.

A spokeswoman for the FDA said the agency was working to reduce the incidence of infections while maintaining access to a crucial medical tool by “actively engaged with the manufacturers of duodenoscopes used in the U.S. and with other government agencies such as the CDC to develop solutions to minimize patient risk associated with these issues.… The FDA believes the continued availability of these devices is in the best interest of the public health.”

Olympus Medical Systems Group, a major manufacturer of these endoscopes and UCLA’s supplier, said it was working with the FDA, physician groups and hospitals regarding these safety concerns and that all of its customers who purchase Olympus duodenoscopes “receive instruction and documentation to pay careful attention to cleaning.”

UCLA said it is notifying 179 patients and their primary-care doctors by phone and letter. UCLA offered to send patients a free home testing kit for a rectal swab, or they could come in to be tested.

Even before this incident, UCLA has struggled at times with patient safety. An influential healthcare quality organization gave the Ronald Reagan Medical Center a failing grade on patient safety in 2012. The hospital’s score improved to a C in the latest ratings from Leapfrog Group, a Washington nonprofit backed by large employers and leading medical experts.

Meanwhile, some doctors worry the outbreaks might deter patients from seeking care they need. “ERCP is a common and critical procedure in most hospitals today,” said Dr. Bret Petersen, a professor of medicine at Mayo Clinic’s division of gastroenterology and hepatology in Rochester, Minn. “It’s not a procedure we can allow to be constrained, so this is a serious issue we need to address.”

For Californians, see “How safe is your hospital? A look at California ratings“:

- Kaiser Permanente hospitals consistently post some of the highest safety scores in California

- UCLA Ronald Reagan hospital gets a C letter grade for safety; L.A. County-USC gets a D

See also:

- Q&A: What makes CRE superbugs so dangerous?

- Alarming: Outbreak of antibiotics-resistant “nightmare bacteria” in Chicago

- Gonorrhea is now antibiotic resistant

~Éowyn