Nobody said anything for a month, then Leonardo—a hell of a cute stunt as a maître of marketing operations—admitted the deal, sort of moodily. As for the coach, he raised one eyebrow and gave his best Carlo Ancelotti let’s-not-get-all-wrapped-up-in-it impression. From the look of it, he’s not letting Inside News in for the money, he just wants to prove—there are a lot of people who say he was a flash in the pan. He just want to prove he can do it again.

Then—pow!—the second the flashes go off, Paris Saint Germain is like those little cafés on the Via Veneto used to be. The hierophants are bubbling up on all sides. Jeremy Menez is taking his new King Charles Spaniel haircut for a ride, looking ever so cross, like a bygone Czar glancing at his assorted collection of bibelots and snuff boxes. As a footballing town, Paris is the bootleg capital of the Champions League. Salvatore Sirigu, of course, is a valiant goalkeeper, a Sardinian artifact patrolling the crossbar and spraying passes as if he was reciting Lear monologues from a Bauhaus lectern. The bohos like Momo Sissoko, one of the sorriest of the lot, turned out to be great flaming ingrates. One thing that got them was that no one wanted midfield genius to go get lunch. That, and the way a car showed up with eight cylinders cooing anytime you wanted to go into town.

But everybody is still waiting for Javier Pastore to present his pièces de résistance: a formidable assist from a pedestal, two slaloms of a perversely serpentine quality in search of the goal—to show, in other words, that the young man is not taking a wide seat, as an Argentinean version of Robert Pires, and that his name is not a literal sketch of a shepherd dog with the cows moseying around the marsh puddles. And everybody feels it, Pastore needs another guide to let the magic out. Calypso-like, Pastore has been seduced to Paris, like villagers all over rural France contentedly do, only to discover himself as a loose, zigzag figure: a citizen of a Victorian Don’t-know-where city, or, perhaps, a simple victim to timidity like so many young play-makers and state-counselors of the day—the Russian Arshavin, doing the Arsenal Avenue up under the Bright Light stimulation of the street lamps and now rearing back Arsenal Avenue down as an Amtrak sleeper, or Mr. Free-Flowing himself, Mesut Özil.

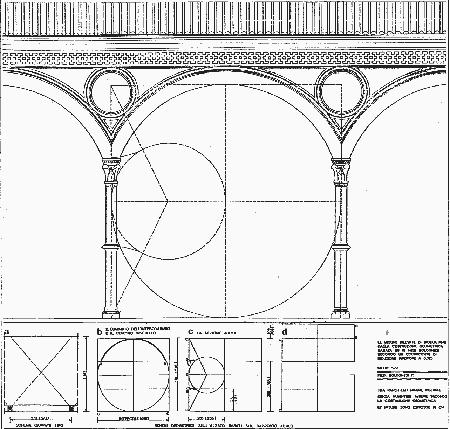

Central Station in Bologna

Wild—gone wild. Unlike a 1980 black Montecarlo spinning out the first turn at the speedway track, Ancelotti ascends to PSG like a real gourmand: he arrives by train. He is the warning bell at the Metropolitan, ordering new players a la carte to the content of his ruby cheeks. His predecessor, Antoine Kombouare, was also a bell: of a grocery store with the pinball machines, of a boxing ring. Before he quit his job at PSG, he had been described by The Times of India as ‘explosive’ or ‘rugged’ and indeed there are only a few trades, such as the whiskey business or the corn field, that produce the kind of man who could convert a sturdy 4—4—2 formation into the pan-European jargon of 4—2—3—1: each legendary and French, each craving to win the soul’s satisfaction.

If honor and courage generate the most daring men in sports, Kombouare’s insistence on advancing the run of play through midfield darkness shows that his bravery did not derive from the rural Southern code, but from the Appalachians; his ethos was crafted by the Korean War, not in Junior Johnson’s side porch. (He was almost like the Renaissance Turk that way—the way, that is, he brought the characteristics of his preferred formation into the extremes of the pugilistic and the schizoid.) Ancelotti, though, is not exactly a man you could find in a grocery store, or a soda-pop cooler filled with iced Dr Pepper cans. He does not eat dried sausages, and is not known for chewing tobacco. He doesn’t even change his expression much during the game, apart from that dutiful, forward-tilted gait that coaches get after twenty years of walking by the sideline. And, of course, apart from his famous Carlo Ancelotti fey-bemused look: the one that seems to be saying, “I don’t know what’s happening, but we’re not going to take it very seriously, are we?”

In an era of Brandoism and Mitchumism in football heroes, Ancelotti is left, by default, in sole possession of what turned out to be the Cary Grant position: a romantic bourgeois hero.

It’s hard to detect in Ancelotti the New Dandy, wearing aviator clothes exclusively, plucked from cart-pullers in the Garment District, nor would one easily find in him the Modern Churchman, reaching to the urban young footballers from their peekaboo gore-tex collars. No necking under the flood lights. None of those fabulous Rolls-Royce maroons, or the Audrey Hepburn sunglasses. But if the problem is to fast-track your sagging trequartista and to make your team swing in a rich and underplayed style, like a viola ensemble, well it has to be Carlo Ancelotti—the Moby-Dick of changing fashions and coaching power-structures.

Architectural section of the Portico dei Servi in Bologna

Old-school strollers in Piazza Maggiore

What about Ancelotti? Just because one lives in Paris and was both a legendary Italian player and coach, always at odds with the pimping Presidents and the Biggies weekday resort, like a genuine Pirelli tire wearing out at NASCAR—a sort of gruff, sentimental Mom’s Pie lifted from Milan’s Wild West Show—there is no need to give the whole business up. Never mind Leonardo’s wacky charisma, the wet smacks on the promenades, women in black stretch nylon stockings looking all week for somewhere to wear them, better still if wrapped around the raw testicles of a soccer dressing-room. In Paris the Tour St-Jacques is nearby the Centre Pompidou, the old and the new religion, Art and Food, while soccer is roaring up and down like a comet with the little stars careening dust at the end. Ancelotti is in Paris to serialize himself, to provide fragmentary biographical materials to the philosopher. Behind his tactical musings there are various esoteric understatements, often cryptic—he is, in fact, like a Diogenes without the tennis sneakers and a Flaming Fork as his inner cover of Life.

The centripetal gesture of Ancelotti’s 4—3—2—1 thickens on the top like a slice of freshparmigiano. That masterpiece of a footballing shape, authenticated as the ‘Christmas Tree’ because of its small hips, is perennially leaning like the Twin Towers of the Po Valley, raising from foggy echoes of courtyard chickens in Piacenza and clinging to the ribs of the Jewish ghetto to stand over the social body of Bologna—a twisted, boyish body where the clouds are rushing, and where the sweat drips like in between the frets of an accordion, as sweet as the fried butter of the relentless pachanga spinners who roll mashed ravioli over pre-Raphaelite aprons.

The thing is, an old boy from the loblolly flatlands of Reggio Emilia knows how a Sunday at the games is supposed to work out: the mob at church, foppish and earnest; the inevitable boredom nudging in; hundreds of motorcycles parked at the stadium—long, long fingers and wrong sweaters over their naked asses, cheeks red like a Rubens on the wall, talking on their telephones. These are the children of suburbia, looking like outcasts in 1921 Le Havre; this is the netherworld of Italian teen-age life, out of what was for years the marketing corner of Vasco Rossi, the chief-musician of the tribe, carved out like rock and roll itself—singing like Judas on the cross at a madder and madder rate, a mixture of camp and Artistic Alienation like the fortunes of Reggiana, Parma and Modena in and out the soccer league.

Ancelotti is the ultimate Sartor resartus, the tailor re-tailored of literature. His life can be existential, but without mustaches or the cheap black turtlenecks of the Collège de France in the 1970s, or else it can be transcendental, but only according to the ironic techniques developed inTristam Shandy. His work contains the kernel of a very Fichtean conception of footballing shapes. Ancelotti, the man who managed to let Kaká, Shevchenko, Pirlo and Seedorf coexist, without hurting or drudging away, does not start from the acceptance of a soccer God, but from the absolute freedom of the will to reject evil on the pitch, and to construct meaning. In an era of Brandoism and Mitchumism in football heroes, Ancelotti is left, by default, in sole possession of what turned out to be the Cary Grant position: a romantic bourgeois hero. The key image is an awesome montage of half-strikers, not the current guerrilla midfielders of AC Milan, popping neck veins and tattoos. (The footballing woman of Mr. Allegri is a Ronda or a Jessica who asks no lasting identification, other than a Brandoesque torn strap-style undershirt; Mr. Ancelotti’s soccer girl is a Gina Lollobrigida type, who likes to enjoy a love scene without taking her shoes off—an enthusiastic suburbanite, unfailingly middle-class.) Ancelotti at Chelsea could not make a good beatnik Cockney like Cary Grant, but the team has rarely looked more formidable and competent, if not under Mourinho’s tycoon-care. Old Carlo is No. 1 box-office material, and when the coach is doing his famous Ancelotti mock-quizzical look, talking nice to soccer-stricken fans in Paris, it’s like seeing a foulard on a mustard-yellow Edwardian chair. The mind boggles, baby. ♦