Debora Spar is the president of Barnard College, a women’s undergraduate college affiliated with Columbia University. Since her arrival at the College, Spar has been a vocal proponent of women’s education and leadership, spearheading initiatives that include the Athena Center for Leadership Studies, an interdisciplinary center devoted to the theory and practice of women’s leadership, and Barnard’s Global Symposium series, an annual gathering of high-profile and accomplished female leaders held each year in a different region of the world.

A political scientist by training, Spar’s scholarly research focuses on issues of international political economy, examining how rules are established in new or emerging markets and how firms and governments together shape the evolving global economy. She is the author of numerous books, including Ruling the Waves: Cycles of Invention, Chaos, and Wealth from the Compass to the Internet (2001) and The Baby Business: How Money, Science, and Politics Drive the Commerce of Conception (2006).

Spar is a graduate of Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, and received her doctorate in government from Harvard. She is a member of the Academy of Arts and Sciences and currently serves as a trustee of the Nightingale-Bamford School and a director of Goldman Sachs. Prior to coming to Barnard, Spar was the Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration and had served as senior associate dean for faculty research and development at Harvard Business School. At Harvard she taught courses on the politics of international business, comparative capitalism, and economic development.

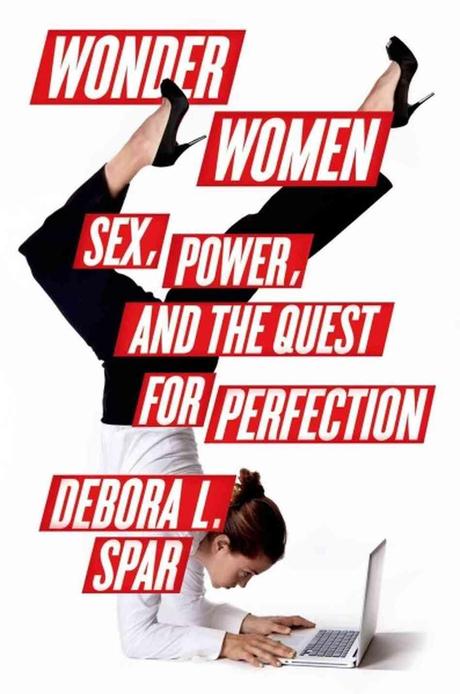

Her most recent book, titled Wonder Women: Sex, Power and the Quest for Perfection, was published in September 2013 and Spar recently spoke to the FBomb about the themes of this book.

How do you think the argument presented in your book is different than Sheryl Sandberg’s or Anne Marie Slaughter’s?

First of all, I want to say that it’s great that all of these books are coming out. It’s a big field. The more books on the subject the better, and I hope we start to see a more diverse set of books come out.

Sheryl’s book is really focused on the business world and what women as individuals can do. It’s very much a book focused on the woman as the unit of analysis – what women can do in the business world. Anne-Marie’s is sort of on the other end of the spectrum. Most of her book sort of takes place in the government sphere, which is her world. Sheryl knows the business world and Anne-Marie knows the government world. And Anne-Marie’s is much more structural analysis – it’s about how society needs to change to accommodate women.

Mine is smack down the middle – which means I’m not going to sell as many books as them because mine is in the messy middle. But that’s what I wanted it to be. I also started writing it way before either of them were in this topic so it’s not a response to them. But I don’t think women’s issues are caused by their own personal characteristics or operating styles and I don’t think women are going to change the sphere by behaving differently as individuals. By the same token, I wish there were some easy structural solutions to the issues women are facing but I don’t think there are. And even if there are some better alternatives – everybody always talks about Scandinavia – the U.S. Congress can’t even pass a budget right now, so the likelihood that they’re going to pass subsidized daycare I think is just a fantasy.

So, I’m smack in the middle, saying that life is more complicated, there are no easy solutions and we’re going to have a lot of everything. We may have to behave slightly differently, we need structural solutions, we also need workplace solutions, changes in the schools – we need a lot, a lot of different things.

This book takes such a rational, economic approach whereas this conversation is often focused on theory. Especially since women historically have not had economic access or autonomy, do you think approaching this topic through that lens is key to finding a solution?

I think – and obviously I’m biased because I wrote the book – but I think it’s a useful voice to analyze the conversation. Feminism for decades was dominated – and to some extent is still dominated – by theoretical conversations. That’s what academia does. One of the things – and I’ve written lots of different books – but one thing I think all of my books have done a good job of in very different realms is translating theory for more general audiences. That’s what this book does. I learned a lot from reading feminist theory but I don’t write in theoretical terms because I think most normal people don’t think or act in theoretical terms, they think in economic terms, they act in concrete ways. I try to be practical, I try to be realistic.

There seems to be a taboo to some extent around arguing that women can’t have it all – it’s often seen as anti-feminist to suggest women can’t do everything or be anything. What is your response to that?

I think we are way too caught up in the semantics of this. I don’t know who coined the phrase “having it all” because it’s a really bad phrase – I think it distorts the conversation. By the same token, I think if you want to use the phrase – fine. I think we need to focus on the reality of women’s lives rather than on the slogans because it gets us into these silly fights.

Why haven’t men been more included in this conversation? Do they exclude themselves because of their privilege or should they be having their own, separate conversation about these issues?

I think it’s a combination of things and I think it’s evolving. So if you go back to the 1960s and 1970s, men were part of the problem. There was a patriarchy that wasn’t very accepting of women for all kinds of complicated reasons. I think it’s hard to put myself back at that point in time, but I can imagine if I had been looking at these issues in 1973 I would not have included men as most people writing at that time did not. But now, in 2013, my overwhelming experience has been that most men want to solve these problems. They want to solve these problems because from their professional perspective, they’re investing in women and losing them. Most men are fathers to daughters, just demographically speaking, and I have seen the strongest proponents of women’s education coming from men. Men want their daughters to succeed. I think the time has really come to bring men into the debate if for no other reason than they still hold 85% of positions of power. So I’m enough of a political scientist and a realist to know that if you want things to change you have to go to people who have the power, and that’s still men. And, the last piece of it is I think men feel very nervous about this argument in part because much of the feminism they’ve been acquainted with is angry, it is about the patriarchy so they feel that they don’t have any seat at the table.

How can we better include men?

Sheryl Sandberg has done a good job of this, Anne-Marie is about to do a pretty good job and I think I’ve done a pretty good job of saying we want men to be part of it. So if books that are starting to get attention say they want men to be part of the debate, it helps normalize it. There’s increasing traffic on the internet about what men can do to help women to succeed, which I think is helpful. I think there’s a lot that can be done in the major corporations and organizations. So I always say if I’m giving a talk for a corporation about women’s role in the corporation, if I’m only speaking to women, I know they’re not serious. But if I’m speaking to a room that’s half male and the male CEO comes to the talk or the event then I know they’re serious.

You call yourself a reluctant feminist, many young women are reluctant to call themselves feminists. What do you think creates the gap between young women’s perception that equality has been achieved and the reality women face in the workplace that it has not?

Well I think many people my age and younger are reluctant feminists because we thought we wouldn’t have to be anymore and I think that’s the idealistic part. I’m not reluctant because I have a problem with feminism, I’m reluctant because I thought we were done with this. I think that’s a piece of it and I think the other piece is young people are impressionable. If 18-year-olds have been surrounded the entire time of their adolescence and childhood with “You can do it all” and “Girl power” and “Girls rock” of course they believe there’s no problem. It’s not that they’re naieve or shallow – it’s that nobody has told them otherwise. They watch television and they see a lot of powerful women role models. They turn out to be grossly unrealistic role models — they’re solving crime scenes and they look like Victoria’s Secret models. But if that’s all you see then it’s no surprise that you don’t hit reality until you’re forced out into it.

What did you encounter that made you rethink calling yourself a feminist?

It was less overt sexism than it was just the dawning realization that my life was different. There was the time when a colleague told me I should end class by jumping out of a cake, or people would tell me I was getting high student evaluations because they liked – pick a body part. Student comments were horrible. That was probably the most shocking: Harvard Business School is a serious place and when half of the comments were about parts of your body, that was pretty harsh. But it was more of the “I’ve got to teach for 10 hours tomorrow and it’s 3 in the morning and my kid’s got the croup and I have to be here, I have to be awake, I’m going to be exhausted tomorrow, I have to live on caffeine.” It was that constant exhaustion more than the overt sexism that got to me.

You posit sisterhood as a possible solution to this. What concrete things can women do to band together?

The first thing women can do is to stop beating each other up. I don’t buy into the argument that several people have said to me recently that women are all catty, out to kill each other. I don’t buy that. I do buy into particularly the very quiet but powerful disparagement of working women against moms and moms against working women. We need to stop that. And again you can’t regulate that solution but one of the things I say all the time when I’m talking to working women’s networks is: invite the women who stopped working to come to these meetings. When you have a meeting of professional women in finance, why not invite the women who were in finance but who are now at home? PTAs are on the other side, they have to be more reasonable about the time commitment they expect, schools have to be more reasonable about the amount of parental involvement they want at certain times of the day. So if you just think about a community of parents around an elementary school – there are things parents can actually do rather than you tend to get these factions going.

In terms of the college campus, instead of slamming people on social media because their eye makeup wasn’t perfect, just say something nice. Just move away, stop bragging about how much you’re doing. If I hear one more person telling me she’s triple majoring or she’s had 42 internships – stop! What did you do this weekend? Say I picked lint out of my carpet – we have to stop bragging about business. We all do.

As the president of Barnard College, do you have any tips for rising freshman women about how they can leverage their college experience to end these forces of perfectionism and navigate the choices they have?

Don’t try to do everything. You want to sample from the buffet but not eat all of it. You’re much better off finding two things you really like than doing a little bit of everything. One phrase I’ve been using a lot that seems to work is that it’s always safer to say ‘no’ than it is to say ‘maybe’. ‘Maybe’ is what kills you. Once you say maybe – whether it’s maybe I’ll come by the party or maybe I’ll stop by for brunch tomorrow or maybe I’ll join the Bollywood dance troop – then you feel guilty if you don’t do it. Then you have something weighing over your shoulder. Then you spend psychic energy worrying about ‘Oh I can’t do that but I’ll let Susie down if I don’t do it.’ Whereas if you just say no upfront – ‘I’d love to do the Bollywood dance troop, but I just can’t’ – sans explanation, I just can’t, it’s so much safer. We all try to come up with excuses for why we can’t do things and that’s what kills you.