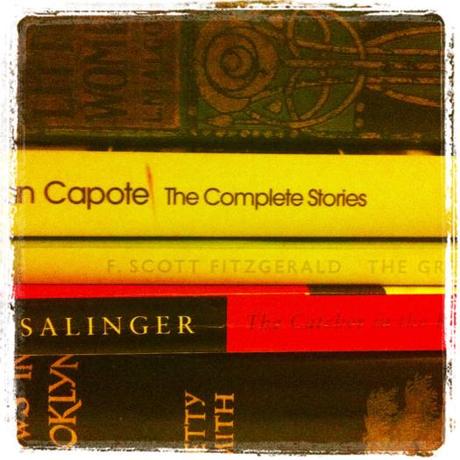

I started an American Literature Book Club at school a few months ago. We’ve read an eclectic mix, from Truman Capote short stories to Little Women, with detours to take in The Catcher in the Rye and The Great Gatsby. It’s been an interesting journey for me as much as it has been for my students; I’ve re-read books I first read without much thought or discernment as a teenager, and been surprised by my reaction to them as an adult. I’ve discovered writers I’ve been meaning to read for years, and found new favourites as a result. So much of what I read in the normal course of things is about the same society, the same culture, the same history, the same surroundings; the settings and the people are distinctively British and instinctively familiar. American literature is a welcome change, opening my eyes to new cultures, new histories and new places. The writing is subtly different, too, in ways I can never quite put my finger on. I never got used to the florid and rather earnest style of newspaper reportage in the US, and the language of American writers is similarly discordant with their British counterparts. It is a window into a different view of the world.

The Catcher in the Rye was my first great surprise. Many people say that it is a book for teenagers and adults tend to find its teenage protagonist self indulgent and irritating. I have had the opposite experience. I read it at 16, and was underwhelmed. I didn’t really understand Holden’s restlessness and self destructive personality; his world was too far from my own for me to relate to it. Reading it as an adult, I was overwhelmed with sadness for this lonely, lost boy whose parents have withdrawn from him in their grief for his dead brother. Unable to cope with his loss, Holden builds a barrier of indifference around himself, rebuffing the kindness of those who do try to help him because he can’t face having to reveal the pain that lies beneath that careless exterior. His relationship with his sister is powerful and touching; through his concern for Phoebe, we see his true personality. Behind the rude, destructive facade, he is a kind, caring, loving boy, longing to make meaningful connections with other people. His brother’s death has made him question life; he sees no joy, no happiness, no hope, in a world where such tragedy can strike and rip out the heart of our existence in a matter of moments. He is looking for answers, and can find none.

He will, in time, find his way, but this razor sharp portrayal of the stripping of trust in life that happens when we reach the cusp of adulthood is brilliant and demonstrates perfectly the vulnerability of the young. My students’ response proved to me that this is not, as so many say, a teenager’s novel; they could not understand Holden, and struggled to see the point of the book at all. When I told them my own thoughts, it was as if I had read a completely different story. They had not noticed the importance of that character, they had not understood why this or that had happened…the conversations we had were fascinating as I helped them to pick apart the reasoning behind Holden’s behaviour, and they discussed their changing impressions. Many said they would re-read it, with these new perspectives in mind. However, I don’t think they’ll truly appreciate it until they’ve passed that tipping point from innocence to experience. Few writers can create such compelling characters who stay with the reader so powerfully, and can continue to touch them in different ways throughout their reading lives. I wish J D Salinger had written more.

The Great Gatsby was my second surprise. I read it as a teenager and thought it was fascinating and profound in its exploration of the hollowness of upper class life. This time around, I found it self indulgent, overwritten and cold. Fitzgerald could certainly write outstanding prose; there are many beautiful phrases throughout that took my breath away. However, there is a self conscious quality to his writing that irritates, and I couldn’t care about any of the characters, none of whom were as fascinating as Fitzgerald seemed to think they were. I couldn’t understand Gatsby’s obsession with the pampered and childish Daisy; I never saw the heart I presume she was meant to have hiding somewhere beneath her frivolous and spoiled exterior. Therefore, I never sympathised with him, and I certainly couldn’t grieve him despite the poignant loneliness of his death. I know the whole point of the novel is to show the emptiness at the core of the glittering American Dream, but considering Fitzgerald’s own relentless pursuit of this halcyon world he recreated on the pages of his novels, this message doesn’t really ring true. There is a falseness behind the words, a lack of heart, that I found insurmountable. It’s no classic for me.

Immediately after reading The Great Gatsby, I picked up A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, one of my absolute favourites. Instantly immersing myself into the lives of the Nolan family, whose warmth and vivacity light up the pages, I understood the main reason why I didn’t enjoy The Great Gatsby. I can’t feel involved in the lives of people who live in an alternate world of unthinking privilege, where problems can be solved with a hastily written check and a trip abroad. There’s no truth for the majority in this depiction. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn shows the real America; people working their way from the ground up to make a better life for their children. Most will never have riches and most will never see their dreams come true, but they have a spirit and a fire that the cool and languid characters of Fitzgerald’s world lack. They are alive, struggling, fighting, striving, pushing themselves forward and dragging their children behind them. They do not glide along carelessly in a world of ease already formed by parents and grandparents who did all the striving for them. They are society at large, reflecting the experience of the average person, revealing the true philosophy and values that underpin American life.

I have only skimmed the surface of all that America’s literature has to offer. The variety of people and experiences and histories spread across the huge mass of North America never ceases to fascinate me, and I love discovering new authors and new novels that teach me more about life on the other side of the pond. One book that certainly should be a classic of ordinary American life, but isn’t yet, is Helen Hull’s Heat Lightening, which has now been reprinted beautifully by Persephone. She is America’s Dorothy Whipple, so even those of you who hate it when I write about American literature (Darlene!) will love it. Don’t bother re-reading The Great Gatsby before the film comes out; read that instead.