After “Landmark” IMF Reforms, U.S. Is Still the Group’s Unrivaled Economic Power

By: Andrew Gavin Marshall

12 November 2015

Originally posted at Occupy.com on 5 November 2015

The International Monetary Fund is one of the three pillars of the global economic system, the other two being the World Bank and the World Trade Organization. And the importance of the IMF cannot be overstated, with its membership of 188 nations (a few less than the membership of the United Nations) and its responsibility to “aid” countries in economic crisis needing loans. The IMF applies strict conditions in return for its assistance, and as such, it has been one of the most influential institutions in the management, maintenance and evolution of the world economic order.

Due to its central role in global financial governance, the management and power structure within the Fund itself reflects the power of some of the IMF’s individual member nations in the wider global economy. The United States, as the largest and most powerful economy in the world, was not only the primary architect of the IMF but remains its largest single shareholder – the only nation with veto power over the Fund’s major decisions.

The IMF was founded in 1944 and officially launched in 1946 with a membership of just over two dozen nations. During the following years and decades its membership grew rapidly. The Fund’s governance structure includes a Managing Director and deputies who are supported by an Executive Board and a Board of Governors. The Board of Governors consists of the finance ministers or central bank governors of the IMF’s member nations, who meet twice a year at the Spring and Annual meetings of the Fund and World Bank, providing national political authority to the direction and decisions of the Fund.

The Executive Board, on the other hand, consists of 24 representatives, usually mid-level bureaucrats from their respective national finance ministries or central banks, who serve at the Fund overseeing its day-to-day operations in close cooperation with the Managing Director. While the Board of Governors reflects the entire membership of the IMF, power at the Fund is not the same as at the United Nations, where one nation gets one vote. Instead, the IMF has a constituency system whereby individual nations are part of larger groups that collectively elect a representative from among their ranks to serve on the Executive Board.

For example, one constituency on the IMF’s Executive Board consists of 23 different African nations who collectively hold 3.34% of the IMF’s voting shares. Most of that influence is controlled by just two nations in the constituency, South Africa and Nigeria. Another African constituency on the Executive Board consists of 23 nations with a collective voting power of 1.66%. This means virtually all of sub-Saharan Africa, representing some 46 nations, has approximately 5% of the voting power within the Fund.

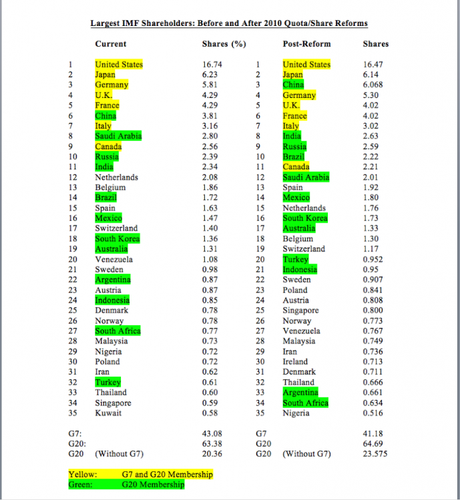

On the other hand, there are nations that do not represent a larger constituency, yet their IMF quotas and voting shares are so great that they have a permanently appointed representative on the Executive Board. The top five shareholders today are the U.S. with 16.74%, Japan with 6.23%, Germany with 5.81%, and France and the United Kingdom with 4.29% each. China, Saudi Arabia and Russia have their own permanent seats on the Executive Board; Canada and Italy are also among the top 10 shareholders in the Fund.

In other words, the major shareholders are the Group of Seven (G-7) nations along with three major emerging market and strategically significant countries. But this was not always so.

Division of Power

In the early 1960s, the largest five shareholders with permanent seats on the Executive Board of the IMF were the U.S., United Kingdom, France, West Germany and India. By 1971, Japan had joined the list and moved above India. The so-called Group of Five (G-5) nations dispatched finance ministers and central bankers who held secret meetings several times a year to steer the global economy.

Quota and governance reforms took place over the years that followed, with countries increasing the amount of money they paid into the Fund and the amount of votes they held over IMF decisions. But the top five largely remained the same. By 1983, Saudi Arabia was added as a sixth member of the group with an appointed director. This composition was maintained into the 1990s, though the pecking order changed (by 1999 Japan had risen to second place, with Germany third and France and the U.K. tied at fourth and fifth).

Not until 2010 did the Group of Twenty (G-20) finance ministers and central bank governors agree to reforms in the quotas and voting shares of the IMF, seeking to increase the participation and ownership of major emerging market economies. The aim was to maintain the legitimacy of the IMF in an era when roughly half the world’s GDP growth was coming from emerging and developing nations. Yet the representation and power of those nations in international institutions remained largely locked in the era of the 1970s. The 2010 reforms, while agreed upon, have still not been implemented due to U.S. Congress’s refusal to ratify them. Virtually every other IMF member nation has ratified and agreed to the reforms, and even the U.S. administration has pushed for the reforms, but Congress remains reluctant due to fears of a perceived loss of U.S. influence over the Fund.

The reality is that the changes in governance of the IMF keep the U.S. as the largest shareholder and still the only one with veto power, though it increases the ownership of emerging market economies, in particular those represented in the membership of the G-20. According to the data of quotas and shares, here is a list of the top 35 shareholders of the IMF, both before and after the 2010 reforms:

In the pre-2010 phase, which still exists at present, the top 10 shareholders are all of the G-7 nations plus China (at 6th place), Saudi Arabia (8th) and Russia (10th). After the reforms are implemented, the U.S. stays at number one, Japan stays in 2nd place, but China moves up to 3rd place followed by Germany, the U.K., France and Italy. Then comes India, Russia and Brazil, with Canada kicked off the top 10 list at number 11. Saudi Arabia has also been kicked off the top 10, following Canada at number 12.

When the G-20 reached agreement in 2010 on the IMF reforms, it was hailed as a “landmark” deal to give developing countries more power and say in the operations of the Fund, with then-Managing Director Dominique Strauss-Kahn calling it “a very historic agreement.” British Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne said at the time of the initial agreement, “We have pulled off major reform of the IMF so it properly represents the balance of economic power in the world.”

The reality, however, is that while China, India and Brazil made significant gains due to the reforms, the overall distribution of power within the Fund remains relatively unchanged. Prior to the reforms, the G-7 nations (U.S., Germany, Japan, U.K., France, Italy and Canada) collectively held 43% of the IMF’s voting shares. After the reforms, the G-7 nations will hold approximately 41% of the voting shares of the IMF. Overall, the G-20 nations (which include the G-7, plus Australia and 11 major emerging market economies) collectively account for 63% of voting shares prior to the reforms, and nearly 65% after the reforms.

Even with these relatively minor changes, the U.S. Congress has failed to pass the reforms, leading the IMF and G-20 nations to seek other “interim solutions” and ad-hoc arrangements until America ratifies the changes. But the hesitation of the U.S. has already had major repercussions, as China founded its own international economic institution, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), threatening U.S. dominance of such international organizations.

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers wrote an op-ed in which he said the U.S. failure to ratify the IMF changes cleared the way “for China to establish the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.” Summers wrote that “with China’s economic size rivalling America’s and emerging markets accounting for at least half of world output, the global economic architecture needs substantial adjustment.”

As history has shown, international institutions are slow to adapt to changes in the global economy, and even slower to adapt to changes in their governance structures. While the U.S. is concerned about maintaining its place at the center of global economic governance, through its inaction and inability to adapt quickly or with substance, it puts its own position at threat and creates the impetus for other nations to create alternatives.

The U.S. has stood at the center of the world’s financial system for roughly 70 years, but there is no reason to assume it will remain there. In an age-old example of national hubris, America’s drive to maintain its centrality – and uncontested power – in the global economy may lead to its eventual replacement.