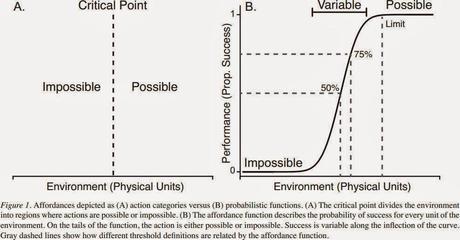

The idea is this: affordance research typically treats affordances as all-or-none, categorical properties. You can either reach that object or you can't; you can either pass through that aperture without turning or you can't. You then measure a bunch of people doing the task as you alter some key parameter (e.g. the distance to the target, or the width of the aperture) and find the critical point, the value of some body-scaled measurement of the parameter where behavior switches from success to failure. For instance, you might express the aperture width in terms of the shoulder width and look for the common value of this ratio where people switch their behavior from turning to not turning.

Franchak & Adolph think this is misleading. Instead of critical points, they suggest it is more common to find thresholds with some level of variability:

Figure 1. Categorical vs probabilistic functions

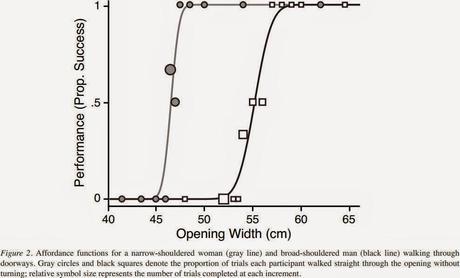

As an example, they measured themselves walking through an aperture and plotted the data:

Figure 2. Data showing performance as the authors try to walk through an aperture without turning

They call the function they fit an affordance function, and there are parameters you can extract including the mean (where the function crosses 50%) and the variability (the slope of the line between 0% and 100% success).This is all standard psychophysics. There are a variety of ways of fitting these functions and modern adaptive techniques that compute the next width to present so as to minimise the number of trials required to get a reliable estimate of the threshold. If you are interested, there is a recent excellent textbook by Kingdom & Prins (2010) that will teach you everything you need to know about doing this work. I actually like the idea of using adaptive techniques to drive the parameter selection, as these methods are typically very efficient.

But the resulting plot is not the affordance.

These functions are not affordancesAffordances are dispositional properties of the world. Psychophysics does not measure properties of the world. It measures the psychological response to those properties, and finds a function that relates the property to the response. Franchak and Adolph mix these levels of analysis up, and argue that the function reveals that affordances can be probabilistic. What it actually shows is that people effect affordances probabilistically. Perception of that affordance, as measured by performance, is variable.

This is well known by psychophysicists, by the way; they would never claim that the property of the world is described by the function relating that property to the perceptual response to that property. To do so is simply a category error.

I think this case reflects the general confusion surrounding affordances - are they dispositions, are they relations? (They are dispositions: properties of the environment picked out by properties of the organism.) People seem to really struggle with this idea, but it's important to get right or else we will be looking in the wrong place for our answers.

This is still useful though

Affordances are not probabilistic. However, the authors are not wrong when they identify that a given aperture close to threshold sometimes allows you through and sometimes doesn't. There is variability in performance. The effecting of affordances is probabilistic.They discuss (quite correctly) that the static geometry of the body (things like shoulder width, or leg length) is not the relevant metric for the perception of affordances. Chemero discusses this in his book (Chapter 7, reviewed here and here); Proffitt talks about 'effort' based metrics to try and address this (e.g. here). Numbers relating to things like shoulder width were a useful proxy for early affordance research (e.g. the classic Warren, 1984 and Warren & Whang, 1987) because they helped show that people do not perceive the world in the units of physics, but in terms of their ability to perform the task - in other words, that they were indeed perceiving the affordances. But there is more to it than this.

More recent work has shown that a better measurement of the person's ability to effect the affordance is in the dynamics of the execution of the action (e.g. Snapp-Childs & Bingham, 2009 plus the references cited in Franchak & Adolph). What matters is how the action unfolds over time; is it a highly variable action? Is that variability noise or something systematic, like postural sway? Both noise and sway affect your ability to walk through an aperture in ways you can perceive and build into your response; if you sway a lot, for example, you need a bigger aperture than someone the same size but who sways less than you. Shoulder width is therefore not the key, but the motion of that width through the aperture is (see also Mon-Williams & Bingham, 2008 for a related analysis of prehension).

What's important about this is that the dynamics of an action can vary from trial to trial in a way that your body geometry doesn't. You might sway more if you are tired, for example. This psychophysical analysis is perfect for identifying this sort of variation. By definition, the function maps a physical parameter onto an individual's psychological response to that physical parameter. Variability in how an individual effects an affordance because of the dynamics of that effecting can be quantified and analysed using this technique. So that's nice, I think; but that's about the limit.

An important note about units

Franchak and Adolph note the following at the end:In this paper, we have exclusively used extrinsic units to describe affordances—centimeters to describe affordances for passing through openings and degrees to describe affordances for walking down slanting surfaces. Although we agree that intrinsic units are important for understanding the specifying information for perception, researchers’ choice to only measure intrinsic units assumes rather than identifies the factors that determine a particular affordance. Prior to gathering evidence about putative intrinsic units, a more agnostic, empirical approach is to measure affordances in extrinsic units.The issue of identifying the action related units in which the affordance lives is indeed a tricky one. However, this agnostic approach is not the solution; task dynamics is. A detailed task analysis can provide a dynamical level description of the task at hand, which then provides a constrained list of task relevant variables (resources) and the information for those variables. This (I'm arguing in an upcoming paper on throwing) is the future of affordances; more on that later when that paper is actually done.

Summary

Affordances are not probabilistic and they should not be equated to the psychophysical function relating the world and behavior. These techniques might be a handy way to look at affordance data in order to start getting serious about individual variation and the factors that drive that variation, but that's about it. The future of affordance research is task dynamics, not psychophysics, and this paper simply spends too much time confusing various levels of analysis.References

Franchak, J. M., & Adolph, K. E. (2014). Affordances as probabilistic functions: Implications for development, perceptio nand decisions for action. Ecological Psychology, 26 (1-2),109-124. DownloadKingdom, F. A. A., & Prins, N. (2010). Psychophysics: A practical introduction. New York: Academic Press.

Mon-Williams, M. & Bingham, G.P. (2011). Discovering affordances that determine the spatial structure of reach-to-grasp movements. Experimental Brain Research, 211(1), 145-160. Download

Snapp-Childs, W. & Bingham, G.P. (2009). The affordance of barrier crossing in young children exhibits dynamic, not geometric, similarity. Experimental Brain Research, 198(4), 527-533. Download

Warren, W. H. (1984). Perceiving affordances: Visual guidance of stair climbing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 10, 683-703.

Warren, W. H., & Whang, S. (1987). Visual guidance of walking through apertures: Body-scaled information for affordances. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 13, 371-383.