Christianity is a supernatural religion. In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth. The Bible is replete with signs, wonders and miracles of every description. Jesus healed the sick, raised the dead, walked on water and, most spectacularly, rose victorious from the grave.

The first generation of Christians believed they were living in the last days. That is, they expected their Christ to return on the clouds of glory to judge the quick and the dead and they expected these events to play out in the very near future. The first Christians prayed for the sick (often with spectacular results), they spoke in tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance, and they prophesied in both the “foretelling” and “forthtelling” senses of that fraught word.

But as years stretched into decades, then centuries, reality began to tamp down the rampant supernaturalism of the early church. Theologians still believed that Christ would return to usher in the new heaven and new earth, but the church’s focus shifted to the fate of the individual believer after death. Would it be heaven, hell or purgatory? And what could be done to obtain a ticket to heaven, avoid hell and keep the stay in the purifying fires of purgatory as brief as possible.

Belief in a literal seven-year tribulation and thousand year millennium faded.

Christians no longer spoke in tongues (at least not in public worship) and although they created set prayers for the sick, no one expected these prayers would always, or even typically, be answered.

The doctors of the church advocated what is now called “cessationism”, the idea that the miraculous gifts described in the New Testament were for the apostolic age only and have now ceased. The Roman Catholic Church believed in the sort of miracles it could control and exploit (especially when hawking indulgences) but these were considered rare and the exclusive province of the saints.

During the Middle Ages, with church and state merged into one Holy Roman Empire, the folks on the “holy” end of the equation worked hard to get along with the empire people. It was essential that control of the church’s message remained in the hands of the literate clerical classes and that the rabble sit silently and listen. If the laity couldn’t understand the Latin mass, so much the better; ignorance protected them kept them from dangerous ideas.

In an age when being on the wrong side of the power equation carried deadly consequences, the leaders of the church had to be as pragmatic and strategic as serpents. In this uneasy environment, unrestrained outbursts of spiritual enthusiasm sent shock waves through the religious establishment, both Protestant and Roman Catholic. Even the act of translating the Bible into the coarse vernacular was regarded with horror. Given the wild variety of material in the Holy Book, God only knew what the rabble might get up to.

“Chiliasts” given to end times speculation and charismatics enamored of the Spirit’s more exotic gifts were widely regarded as simpletons playing with matches.

This view received a slightly different justification from the Protestant reformers grounded in the doctrine of sola scriptura (scripture alone). Once the New Testament had been written and canonized, the reformers argued, “sign miracles” like faith healing, prophesy and speaking in tongues were no longer necessary.

Martin Luther may have lived in a “world with devils filled” but he condemned those who focused on signs and wonders. “Christ has taught and warned me,” the German reformer told his flock, “Hold on to My Word, pulpit, and Sacrament. Where these are, there you will find Me. Stay there, for you do not need to go running or looking any farther.”

While the second coming of Christ remained established doctrine, a literal interpretation of Revelation 20 (with its 7 year tribulation and millennium) was, in Calvin’s opinion, a “fiction” that is “too childish either to need or to be worth a refutation.”

The mystical tradition avoided simple by focusing on the inner life and celebrating the mystery of God. To the mystics, a focus on observable signs and wonders was unnecessary if the Spirit was encountered deep within.

This cautious approach to the supernatural aspects of Christianity flourished within American evangelicalism until the mid-twentieth century. The Pentecostals didn’t get rolling until the early years of the 20th century and were regarded with unfeigned suspicion by liberals and evangelicals alike.

Dispensationalists like J.N. Darby and C.I. Scofield embraced a vigorous premillennialism replete with rapture, tribulation and literal millennium; but they were adamant that signs and wonders died with the apostolic age.

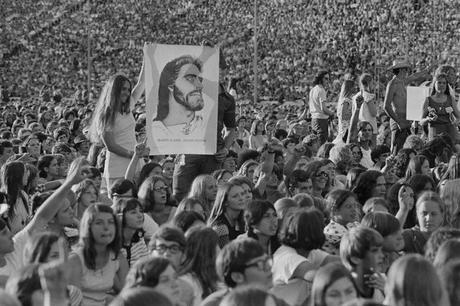

The Jesus People changed all of that. A tiny slice of American young people became hippies, and a small minority of hippies became Jesus People, but in the heart of the Summer of Love in 1967, the Jesus Movement took off like a rocket. Jesus People lived in communes, rejected political, civil and religious authority and took their religion straight from the biblical headlines.

They got high on a God of miracles. The Christ of the Jesus Movement was brimming with power and returning in vengeance any day now.

They spoke in tongues and prophesied because these practices were right there in black and white.

They believed in angels, demons and a prowling devil seeking whom he may devour.

They prayed for the sick with innocent expectation.

They danced, raised their hands to heaven and liked their music loud, rhythmic, romantic and electric. Hymn books and pipe organs weren’t their style. This was the golden age of rock and the Jesus People liked their Christian music loud ecstatic and rhythmic.

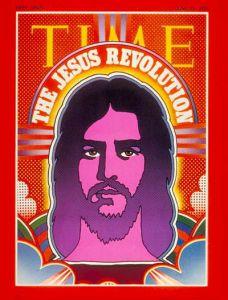

At the height of the Jesus Revolution in 1971, the Jesus People made the cover of TIME magazine.

At the height of the Jesus Revolution in 1971, the Jesus People made the cover of TIME magazine.

It is a startling development for a generation that has been constantly accused of tripping out or copping out with sex, drugs and violence. Now, embracing the most persistent symbol of purity, selflessness and brotherly love in the history of Western man, they are afire with a Pentecostal passion for sharing their new vision with others. Fresh-faced, wide-eyed young girls and earnest young men badger businessmen and shoppers on Hollywood Boulevard, near the Lincoln Memorial, in Dallas, in Detroit and in Wichita, “witnessing” for Christ with breathless exhortations.

Everybody wanted a piece of the hottest religious phenomenon in america. Billy Graham and Bill Bright’s Campus Crusade cozied up to the Jesus People. Johnny Cash got in on the action. Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar were spawned by the movement. Old-time charismatics like Demos Shekarian (the Armenian founder of the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship International) and Arthur Blessitt (a Mississippi Bapticostal known as the pastor of Sunset Strip) gave direction to an explosive but inchoate movement.

Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth was written with the Jesus People in mind and they couldn’t get enought of Hal’s end-time speculation. Lindsey and his ghost-writer made dispensationalism hip. Jesus was coming any minute, you could just feel it.

The Jesus Revolution was short-lived. Unqualified supernaturalism can be exhausting. Erstwhile hippies were getting married and settling down. Communal life is always stressful. Every religious movement hardens into some kind of institution sooner or later (usually sooner) but the Jesus People resisted organization.

Even in 1971, when they sparked a feature story in TIME, cracks were appearing in the facade. A 43 year-old Martin Marty speculated that the Jesus People “frustrated by a complex society that will not yield to their single-minded devotion, may well disband in disarray.” But “Five years from now,” Marty predicted, “you may have some better Presbyterians because of their participation in the Jesus movement.”

Marty was right about the implosion of the movement, but few former Jesus Freaks drifted into Presbyterian churches. Instead, the Jesus Revolution left a deep and lasting imprint on the independent megachurches that drive American evangelicalism and, increasingly, Republican politics. The shift was gradual, but by 1985 the churches C. Peter Wagner calls “the third wave of the Holy Spirit” were reshaping evangelicalism in America (the first wave had been Pentecostal christianity and the second was the charismatic movements of the 1960s).

The megachurches springing up across America took their cue from the Jesus People. Religious pop music (with Jesus as romantic interest), informal worship attire, a focus on charismatic gifts like healing, speaking in tongues and prophecy, and end-times speculation were marketed as a package deal.

With few exceptions, megachurch believers share the Jesus Movement’s theology, but the sheer apocalyptic passion of the 60s is gone. As Marty suggested in 1971, the Jesus People were “frustrated by a complex society” that would not “yield to their single-minded devotion.” Paddling against the cultural current is tough. The new evangelicalism that emerged after 1985 solved this problem by creating a multifaceted counter-culture.

Over the last three decades, a magical version of Christianity has made common cause with

- a magical form of trickle-down economics;

- a magical trust in the power of guns and missles to create peace and security;

- a magical science that dismisses the conclusions of climate science while arguing for a young earth;

- magical media outlets that give credence to this blend of religion, economics and militarism, and

- a political party that allows conservative evangelicals and their counter-cultural allies to win elections.

The rise of Donald Trump reveals the power, potential and manifest danger of this magical marriage. A lie with widespread backing is easily mistaken for the truth.

In my capacity as a hospice chaplain I work with terminally ill patients and their families. When a doctor tells you that you have six months or fewer to live it’s just a guess; but it’s an educated guess. In the past three years I have prayed with hundreds of patients and their families who live with the worst news imaginable. I read the Bible. I pray. But, frankly, the signs and wonders passages can be very problematic in the hospice business, especially for those who place implicit trust in the scriptures. Miracle stories can spark a bogus logic. If Jesus could raise Lazarus from the dead, some reason, surely he can heal my Johnnie. But Johnnie just keeps declining and eventually dies, just as the doctor predicted. Does this mean that Jesus let Johnnie down?

We need the brand of faith that works in the real world. I’m not siding with the cessationists. Telling God that he can’t heal my disease because the Apostolic Age is over is just as presumptuous as demanding that God heal me. Both cessationists and those who demand a sign believe in a logical, predictable God who always plays by the rules. God doesn’t play by the rules. God makes the rules and breaks the rules with impunity because God is God.

A religion that indulges in magical thinking is no better than fanciful science, Alice in Wonderland economics, a foreign policy that trusts in redemptive violence, or news agencies and political parties that prey on popular delusions. Magical thinking always ends in smoke and ash. Faith doesn’t demand exemption from the random horrors of life; faith takes up its cross and follows.