The first "Latin tag" that I remember is the motto of my father's chosen Armed Service, The Royal Air Force, in the mid-1920s through to demob at the end of WWII in the year before 1946 when I was born. I was one among many War Babies in the mid to late 1940s when our fathers returned from walloping The Nazis and their fellow-travellers. The RAF Motto is Per Ardua Ad Astra (Through Toil To The Stars as Dad rendered it, and even at a baby's age, I think I understood that I had to graft away if ever I was to get anywhere).

Even now I can see that Dad's youthful wanderlust - he served in Aden, Singapore and North Africa before coming "back to Blighty", and meeting, courting and marrying Mum, and their settling here in Blackpool - has been passed on to me at least in imagination, and encouraged me to want to learn at least a smattering of languages other than English.

Please listen to this clip before reading the remainder of the article:

Confusing in sound, aren't the various languages, though the closer we are geographically to the country of origin, the more clues there seem to be in similarity of vocabulary?

I'll begin with three short pieces in their original languages which have developed into modern English (which I see as English English) which have stuck with me over the past 50 years or more:

"Ad astra per alia porci" was a favorite insult thrown at us or written on an essay we had submitted by the late Eric Hood, a History master who encouraged us by predicting inevitable failure for us in public exams unless we "bucked up". It was not until much later when I had qualified as a teacher myself that I learned of the insistence by writer John Steinbeck that this phrase appear with the title of whichever of his books was being published. The tag translates exactly as "To the stars on a pig's wings", a slightly more poetic way of saying "You are no writer, sunshine - Give Up!", and the novice Steinbeck had suffered the insult as frequently as we did from one of his tutors who chortled at Steinbeck's stated ambition to become a writer, but Steinbeck "had the last laugh" (often) as the saying goes.

Secondly, "Ou sont les neiges d'antan?" in the 16th. century French of poet Francois Villon. "Les neiges d'antan" is usually rendered as "the snows of yester-year" and which led to the coining of a fresh word into English, borrowing the sense of yesterday into year-long passages of time, and blanketing remembrance into a cloak of colourless and cold snow. I can remember being taught that "antan" carries with it in French so much yearning for what is no longer with us that the English had to create a fresh word to render it more accurately; one of my first lessons in how inadequate it is to render one language into another as our environmental and cultural experiences are so different dependent on where we spend most of our lives. And it is not just a single experience of snow we lament, but the varying experiences year-by-year. The plural form "Snows" gives me the Christmas I emerged from a four-month stay in hospital at five years old, but was not allowed "out" to play in the deep snow, a most unusual occurrence in Blackpool, warmed as we are by the Irish Sea. So my friends from our street congregated outside our front-room window, built a snowman for me in the road, and entertained me with a snowball fight. And through the other rare Winters in Blackpool when the sea and Stanley Park Lake froze, and once when our baby daughter was marooned with her godmother, Judy, near Blackpool Airport at the south end of town while we waited for them in North Shore.

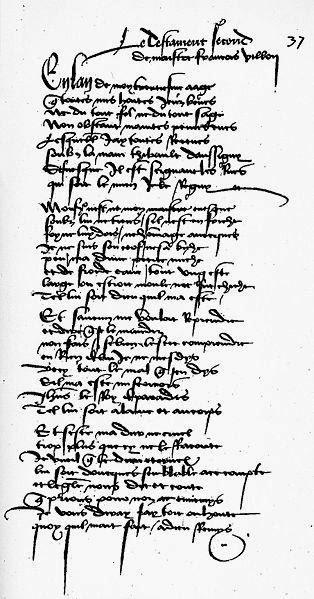

A page from François Villons (1431-c.1474) "Grand Testament de Maistre François Villon"

As this short explanation of the origin of the phrase in Wikipedia makes clear, wondering about the passage of time (or Ubi Sunt? poems) date from Classical times - we humans are forever delving into the past, and regretting the tendency of familiar experiences we enjoyed 'back then" to be no longer available to us:

"The Ballade des dames du temps jadis ("Ballad of the Ladies of Times Past") is a poem by François Villon which celebrates famous women in history and mythology, and a prominent example of the ubi sunt genre. It is written in the fixed-form ballade format, and forms part of his collection Le Testament."

The section is simply labelled Ballade by Villon, but the title des dames du temps jadis was added by Clément Marot in his 1533 edition of Villon's poems proving how publishers and even their printers may adjust what the reader believes is the author's choice of words. And "antan" and "jadis" though both referring to Times Past require a different nuance when translated into English English.

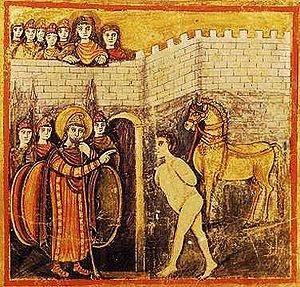

Finally, the phrase "Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes" in Virgil's Latin of The Aeneid (II,49) original has been useful in so many different settings. It has been paraphrased in English as the proverb "Beware of Greeks bearing gifts", even though its literal meaning, "I fear the Danaans, even those bearing gifts", carries a somewhat different nuance to the usual English version of the phrase.

Its origins are related in the Aeneid thus. After a nine-year war on the beaches of Troy between the Danaans (Greeks from the mainland) and the Trojans, the Greek seer Calchas induces the leaders of the Greek army to offer the Trojan people a huge wooden horse, the so-called Trojan Horse, while seemingly departing.

The Trojan priest Laocoön, distrusting this gesture, warns the Trojans not to accept the gift, crying, Equō nē crēdite, Teucrī! Quidquid id est, timeō Danaōs et dōna ferentīs. ("Do not trust the horse, Trojans! Whatever it is, I fear the Danaans, even when bringing gifts.") When immediately afterward Laocoön and his two sons are viciously slain by enormous twin serpents, the Trojans assume the horse has been offered at Minerva's (Athena's) prompting and interpret Laocoön's death as a sign of her displeasure. Minerva did send the serpents and help to nurture the idea of building the horse, but her intentions were certainly not peaceful, as the deceived Trojans imagined them to be. The Trojans agree unanimously to place the horse atop wheels and roll it through their impenetrable walls. Festivities follow under the assumption that the war is ended.

During the Cold War of the late 1940s through to the 1970s there have been numerous occasions when uttering "Timeo Danaos...", the abridged version of the tag, has been too frequently appropriate, and unfulfilled promises are the bane of any diplomat's life.

Today, I'd argue that Ian Duncan Smith's insistence that he is changing things "for the better for everyone" through attempts to introduce Universal Credit should have Timeo Danaos... stamped on every mailing from the Department of Work and Pensions.