Martinho and Kacelnik have shown that duckings imprint on the relational concept of "same or different." From Wasserman's perspective on the work:

Adhering to the adage that “actions speak more loudly than words,” scientists are deploying powerful behavioral tests that provide animals with nonverbal ways to reveal their intelligence to us. Although animals may not be able to speak, studying their behavior may be a suitable substitute for assaying their thoughts, and this in turn may allow us to jettison the stale canard that thought without language is impossible. Following this behavioral approach and using the familiar social learning phenomenon of imprinting, Martinho and Kacelnik report that mallard ducklings preferentially followed a novel pair of objects that conformed to the learned relation between a familiar pair of objects. Ducklings that had earlier been exposed to a pair of identical objects preferred a pair of identical objects to a pair of nonidentical objects; other ducklings that had been exposed to a pair of nonidentical objects preferred a pair of nonidentical objects to a pair of identical objects. Because the testing objects were decidedly unlike the training objects, Martinho and Kacelnik concluded that the ducklings had effectively understood the abstract concepts of “same” and “different.”

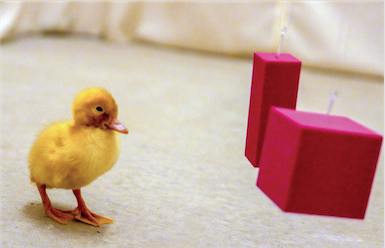

A duckling in the testing arena approaches a stimulus pair composed of “different” shapes.

This study is important for at least three reasons. First, it indicates that animals not generally believed to be especially intelligent are capable of abstract thought. Second, even very young animals may be able to display behavioral signs of abstract thinking. And, third, reliable behavioral signs of abstract relational thinking can be obtained without deploying explicit reward-and-punishment procedures.