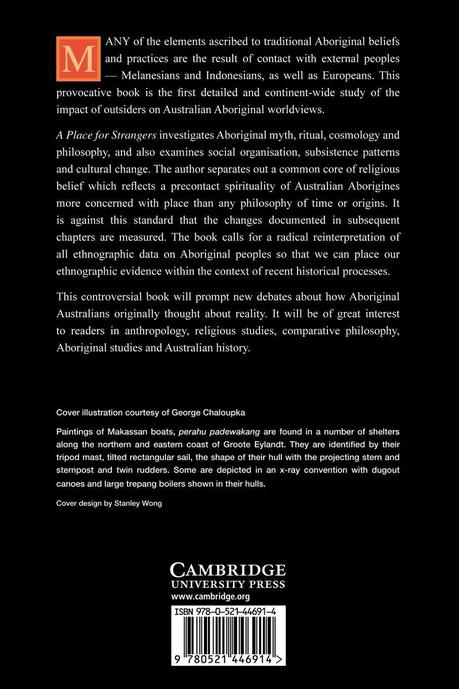

It has been difficult piecing my mind back together after having chunks of it blown away and apart by Tony Swain’s A Place for Strangers: Towards a History of Australian Aboriginal Being (1993). Swain’s rather innocent sounding thesis is that the pre-contact Aboriginal worldview is rooted in local place rather than universal time. This may not seem like a big philosophical deal, but it is. Like most, I had always assumed that time is a natural category that organizes perception and experience for all humans. According to Swain, it is not so:

Aboriginal people, prior to the intensive disruption of outsiders, had not allowed “time” to develop as a determinative quality of being. Temporal constructs are, I believe, not a “natural” human attribute but rather they are specific forms of intellectual organisation. Why Aborigines avoided this philosophical option is an important issue to which I will soon turn, but for the moment it is enough to recognize that there was no fashioning of time, linear or cyclical, but rather a sophisticated patterning of events in accordance with their rhythms.

Those who have derived their understanding of Aboriginal “religion” or worldviews from Mircea Eliade will of course be surprised by this. Eliade, after all, famously claimed that Aborigines conceived time as cyclical. This conception, in turn, supposedly enabled them to escape the weight of history and made them into “primitive” mystics par excellence. Swain forcefully (and in my estimation, convincingly) rejects this view:

The most sophisticated offender in this regard was Mircea Eliade. His reading of Aboriginal traditions was essentially in accord with his comparativist thesis that cyclical history is a mechanism for overcoming the terror of time.

In a remarkably Eurocentric reading of the ethnographies, Eliade has implied that throughout Australia people recognised a great first cause which amounted to a Supreme Being. His evidence for this claim was in fact confined to two regions, the seat of [colonial] invasion in the south-east, and the intensively missionized Hermannsburg area. Given the fact that the Aranda “High God” held himself particularly aloof from the world, Eliade saw his opportunity to “prove” the original universality of a single God.

What we are witnessing, of course, is Eliade’s own cultural projection, for as he revealed in his journals, the “secret message” in his history of religions was that “myths and religions, in all their variety, are the result of the vacuum left in the world by the retreat of God, his transformation into deus otiousus.” Eliade thus bequeaths Aborigines [a worldview and Ancestral monism that they never possessed].

As I noted in this post, Eliade was a mystic whose personal commitments and agenda often got in the way of his scholarship. While Eliade’s works contain enormous quantities of useful ethnographic information, these Frazerian nuggets are usually embedded in suspect interpretations.

It’s rare that I begin reading a book and know it will forever and fundamentally change the way I think. Swain’s book did that yesterday after only 30 pages. I’m going to have a great deal to say about it over the coming weeks, so stay tuned. And for those with an interest in these matters, you must get it. If you’ve ever wondered what it would be like to perceive and structure the world in a way that is profoundly different or even alien, this book is for you. It’s also an astonishing corrective to over one hundred years of confused and disappointing scholarship on Aboriginal “religion” or worldviews.