New Yorker writers and editors weigh in, here, on "the best books of 2014." If it's fair to assume that the best of the best are the ones mentioned by more than one judge, then the books of the year are the latest additions to Karl Ove Knausgaard's My Struggle and, maybe aided by the author's death shortly after publication, the Collected Poems of Mark Strand.

I did not deliberately abjure the current, but my own reading this year was heavy on some ungolden oldies--the first seven books of the Bible made a substantial part of it, and, I have to say, my interest trended south. Of Paradise Lost, Dr Johnson opined that, lacking human characters, the work almost necessarily lacks human interest, before appending, in one of the shortest sentences he ever wrote, "No one ever wished it longer." Now, the Bible is different, in that it is full of human characters, but the God-soaked pages tend to wring the life out of them, so that human interest sputters out. The parts I remember now are the exceptions to the gray-out--Sarah laughing at God when she overhears Him predict yet again that she will have a child, Moses protesting his deputization. The former:

The Lord said, "I will surely return to you in the spring, and Sarah your wife shall have a son." And Sarah was listening at the tent door behind him. Now Abraham and Sarah were old, advanced in age; it had ceased to be with Sarah after the manner of women. So Sarah laughed to herself, saying, "After I have grown old, and my husband is old, shall I have pleasure?"

Looking up the latter, I see that it does not lend itself to quotation, the effect arising from a long dialog in which Moses protests to God his unfitness for the job and, notwithstanding his supposed ineloquence, responds to God's cajolery with arguments and counter-arguments and counter-counter arguments until, finally, God becomes exasperated. "Okay, okay, I'll get your brother to help you!" he says, in some unconsulted hip new version. "But, please, shut up!" My favorite parts of the Bible occur when people are behaving like people and so is God, but it doesn't happen a lot.

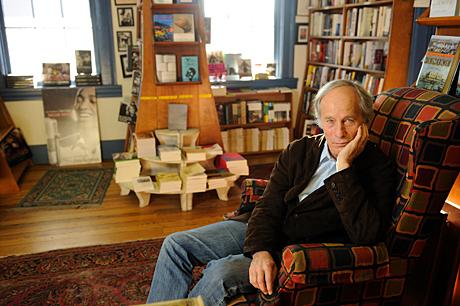

At year end I'm sunk in the middle sections of Richard Ford's The Lay of the Land, which, until this year, was often described as the concluding installment in the Frank Bascombe saga. Everyman's Library even published a thick handsome volume of all three chronicles--the first two were The Sportswriter and Independence Day--entitled The Bascombe Novels, a bookshelf counterweight to Rabbit Angstrom: A Tetralogy. You sort of knew that Updike was done with Rabbit, who, as the title portends, dies at the end of Rabbit at Rest. Though his prostate gland is home to malignant tumors, Bascombe is still kicking at the end of The Lay of the Land, and earlier this year Ford confounded the compendium-makers by adding Let Me Be Frank With You. (Prostate cancer often advances so slowly that "watch and wait" is a treatment option, especially for patients who love having erections or are made despondent by the prospect of incontinence or are old enough so that they are apt to be afflicted by something truly dreadful before the prostate cancer turns deadly.) Part of the publicity for the new book was a Fresh Air interview with Terry Gross, which I heard while washing dishes one night and so was reminded that I own a (previously) unread paperback edition of The Lay of the Land. I'm enjoying it, I think, more than either of the first two books, though maybe it's just a matter of favoring more recent pleasures. What's the attraction? For me, it's mainly the chance to hang out with Bascombe, skulk around with him and listen in on his conversations and hear his thoughts on the view from his car while he runs errands and otherwise prosecutes the daily routine. The effect is cumulative; at first, you might think it's "slow"; but there's enough of interest so that you persevere; the leisurely unwinding of the first-person narrative is like comfort food; and eventually you come to believe that, in Bascombe, you are in the presence of an offhandedly superlative human specimen. Just to give you a little flavor, here he is at a funeral, taking the measure of a fellow mourner (it will help to know that the present time of the novel is Thanksgiving, 2000):

Bud's not talking in the hushed tones appropriate to the dead-lying-inside-the-big-frosted-double-doors, but just jabbering on noisily about whatever pops into his head. The election. The economy. Bud's a trained lawyer--Princeton and Harvard Law--but owns a lamp company in Haddam, Sloat's Decors, and has personally placed pricey one-of-a-kind designer lighting creations in every CEO's house in town and made a ton of money doing it. He's sixty, small, fattish and yellow-toothed, a dandruffy, burnt-faced little pirate who wears drug-store half glasses strung around his neck on a string.

[Snip.]

Bud's a blue-dog Democrat (i.e., a Republican) even though he's yammering, trying to act betrayed by fellow Harvard-bore Gore, as if he voted for him. Bud, though, absolutely voted for Bush, and if I wasn't here, he'd admit right now that he feels damn good about it--"Oh, yaas, made the practical businessman's choice." Most of my Haddam acquaintances are Republicans, including Lloyd, even if they started out on the other side years back. None of them wants to talk about that with me.

[Snip.]

Contrary to expectation, I wish I was inside, standing vigil beside Ernie in his box, and not out here. I remember a night years past when a young, lean but no less an asshole Buddy Sloat--still practicing divorce law and before the unexamined life of lamps caught his fancy--started a row over, of all things, whether a deaf man who rapes a deaf woman deserves a deaf jury. Bud's view was he didn't. The other guy, an otolaryngologist named Pete McConnicky, a member of the Divorced Men's Club, thought the whole thing was a joke and kept looking around the bar for someone to agree with him and ease the pressure Bud felt about needing to be right about everything. Finally, McConnicky just smacked Bud in the mouth and left, which made everybody applaud. For a while, we all referred to Bud as "Slugger Sloat," and laughed at him behind his back. It'd be satisfying now to hit Bud in the mouth and send him back to the lamp store crying.

If you know Ford's "western stories," like the ones collected in Rock Springs featuring small-time criminals and other dead-end, down-on-their-luck guys stuggling to keep their chins above the rising misfortune, you might wonder what his alter-ego is doing selling McMansions--Frank is an affluent realtor operating in New Jersey, the kinds of neighborhoods Tony Soprano lived in--when he could be getting into a fight in a bar in Butte. My theory is that after Ford became a successful author he naturally had more chances to take in another side of American life, the America of Bud Sloat and up-market real estate, etc., and he mastered all that, too.

My other reading highlight from the year was Bite the Hand that Feeds You, the posthumous collection of some of Henry Fairlie's essays. Fairlie was the transplanted British political journalist who, perhaps assisted by being non-native, saw American politics in all its resplendent weirdness. A Tory on the other side of the Atlantic, he abhorred America's conservative party--and he was dead before the Republicans consummated their divorce from reality. There is, surprisingly, local interest, as Fairlie once undertook a motor trip through America and spent one night observing the fauna in a Mankato, Minnesota watering hole. But my favorite essay, as I described here, is his take-down of George Will.

Speaking of Will, I see he wrote, in a recent column, that the invasion of Iraq in 2003 was "the worst foreign policy decision in U.S. history." Now he tells us!