I wasn’t suicidal, but I was curious what would happen. Surely, the live-streaming app bought by the $10 billion dollar company Twitter had thought of this use case. I imagined a notification would pop up, advising me who to call if I needed help, but no, the post went through.

Instantly, fifty people joined compared to my usual two or three viewers, and some messaged homophobic slurs and goaded me on to suicide, but it wasn’t all bad. Concerned people asked if I was okay. Others told me what I was doing was a horrible, irresponsible joke, and one person shared a story about how upsetting my post was as her father had committed suicide on the exact same day a year before.

I felt bad about what I had done, but still felt Periscope should have predicted these situations and somehow handled it better.

Then, three months ago, a French 19-year-old, did it for real–again, goaded on by users.

While the internet may be guilty of ignoring mental illness and victimizing vulnerable, unstable people, the true culprits are the companies ignoring these problems on their networks. We won’t be able to tame the trolls of the Internet any time soon, but social media companies can easily make small changes to their services that have enormous impacts across their huge networks, yet they don’t.

We already have Big Brother, he just only cares about advertising

You might ask, wouldn’t monitoring social media sites for mental illness violate privacy, isn’t it a bit creepy? Social media companies like Facebook already track our every action.We screen posts for nipples, obscenity, hate speech, piracy, scams. We already measure, quantify, and cluster people into all kinds of categories, but only to maximize ad targeting or recommend music. Why not use these same tools to screen for and improve mental health?

Facebook can already detect the emotional valence of Facebook posts,[1] so why aren’t they using this tool to screen for depression or mania? A friend told me in a manic phase he liked so many Facebook groups so quickly that Facebook thought he was a bot and locked the function on his account. Why didn’t it also gently suggest he might be having a mental health problem and nudge him towards getting help?

We’ve known for a long time that slightly altering situations to make suicide more difficult like installing fences on bridges or switching pills from bottles to blister packs can dramatically influence whether people actually act in a moment of pain. We also know that news stories related to suicide that contain information about getting help reduce suicide rates, so why don’t we make our sites provide this information as well? With suicide as the second-leading cause of death in Americans 15-24 (CDC), and 3rd leading cause of death worldwide for 15-44 year-olds (WHO), small changes can have big impacts.

Public Twitter Meltdowns

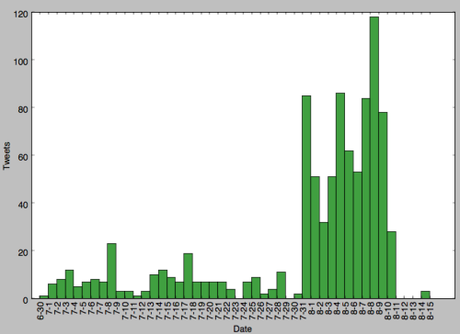

Social media has raised awareness of mental illness, by pushing celebrities erratic behavior into the limelight. In 2011, hangover actor Brody Stephens, experienced his first manic episode and before becoming aware of the condition, essentially live-tweeteed the whole experience. Even completely ignoring the bizarre content of the tweets, can you guess where the manic episode occurred, by looking at the numbers of tweets posted?

But in addition to changes in quantity, and timing of posts, the words themselves are smoking guns. Deleted tweets from this time period, reportedly included: “I’m off Lexapro & I have a gun in my mouth! Do you believe me? #trust #me & #magnets – #5150 on roof, ok? #PositveConnection #belief #daisy”.

Brody later spoke about this period on the podcast Mental Illness Happy Hour:

“Paul: And are you sleeping at this point?

Brody: Not much. Like four hours. And people think I’m up all night. I’m tweeting up a storm, I’m just going nuts on Twitter, so that’s why people know like something’s not right with Brody. Is it a bit for his HBO thing? Is it real? And then I mentioned something about a gun and that’s when like—that caught the eye of a lot of people. That scared people.

Paul: What did you say?

Brody: I said I had a gun, back off, leave me alone, I got a gun. Somebody said I may have said I have a gun in my mouth. I don’t know. But I didn’t have a gun. I didn’t want to hurt myself.

Paul: But you tweeted that …

Brody: I tweeted that because I was getting these calls from all of my friends worried about me. I was like, “I’m fine. Guys, I’m fine. Trust me. I’m happy.” I was out of character, you know…”

~ Excerpt from Mental Illness Happy Hour’s interview with Brody Stevens

The person behind the words – How good does a screening tool have to be?

Brody Stevens’ tweeted about having a gun in his mouth, but he didn’t even own a gun and later claimed to be joking. Though he was mentally ill and in need of help at that time, this example also illustrates one of the potential problems with screening for mental illness over the Internet–It’s hard to tell whether someone is telling the truth or joking. At the time of Brody’s meltdown many people thought it was a publicity stunt or even Kaffman-esque avant-garde comedy. Making sense of someone’s posts is hard enough for humans, let alone for a computer algorithm.

A somewhat related story, told in the documentary Terms and Conditions May Apply is of a man repeatedly googling topics like “how to murder cheating wife.” Clearly someone an algorithm should flag to be checked up on, right? Turns out he’s a writer for Cold Case investing a story. (Some of the google searches I made while writing this article are equally damning.)

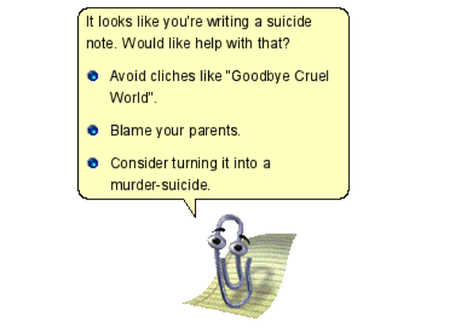

Obviously we don’t want to diagnose or arrest someone based on circumstantial evidence, but the algorithms don’t have to be perfect to be valuable as screening tools. If an algorithm says someone is likely to be suffering from a problem, the system can gently and unobtrusively offer help:

“We noticed some frightening words in your post. If you are experiencing distress or need to talk to someone please call this hot-line for help: 555-5555. Click here to ignore this message and others like it ■” (I don’t know something like that…)

The other person behind the words – taking seriously the deranged

Conversely, in real life, we use many non-verbal cues to assess someone’s mental state, walking down a city street if someone walks up to you, you’ll probably instantly assess:

- Are they disheveled or well groomed?

- Do they make normal eye contact?

- What is their emotional state?

- Are they speaking at a normal speed with typical inflection?

- Do they appear to be on drugs?

But none of these factors are available on the Internet, so the actions of people in altered mental states can go unchecked and be misinterpreted. Add to this fire the blazing speed of the internet and people quickly make a series of mistakes:racking up credit card debt through reckless purchases, emailing a psychotic rant to their entire address book, etc. (both common symptoms of mania, by the way.)

Over the internet, we may take seriously or attach judgments to people’s statements and actions, whereas if we saw them in real life, we would realize the state they are in and respond to their actions in a completely different way.

But ignorance to and denial of mental illness on the internet go beyond the medium of text, and reflect our culture’s squeamishness with the subject. For example, two weeks ago, when fashion YouTuber Marina Joyce began acting erratic, the internet was quick to propose a number of outlandish conspiracy theories. People worried she was being held hostage rather than accept a much more likely possibility—that she might be a person experiencing a problem with drugs or mental illness and in a vulnerable state. Twitter users were so vocal about it, they even prompted police to investigate her apartment.

So, what is being done now?

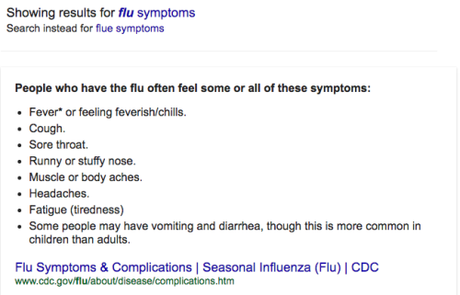

Shockingly little. For example, if I google ‘flu symptoms,’ hell if I misspell it and google ‘flue symptoms,’ google feeds me a featured snippet about the influenza:

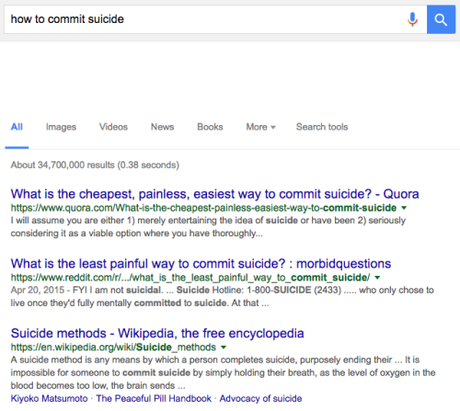

But if I search ‘how to commit suicide’ there’s no curated content, it just feeds me the top websites with suicide information:

Luckily, in the top links to Quora and Reddit, users have taken it upon themselves to share suicide prevention information (though it is not universal information and google could feed the correct information based on people’s location). However, we shouldn’t rely on the benevolence of strangers on the internet, we should make sure that access to care is given to people at these crucial junctures.

Facebook actually implemented a new feature for suicide prevention in 2015, as I learned after originally publishing this article. Though it is triggered first by human report, and then trained professional oversight, the system then presents a fairly sophisticated flowchart of options, that lets users seek help at a level they are comfortable with.

Research into these sorts of issues is starting to get funded. For example, earlier in 2016, University of Ottawa’s Diana Inkpen was granted $464,100 for “social web mining and sentiment analysis for mental illness detection.” Such research is part of the growing field of Cyberpsychology, which essentially studies both how people’s psychology influences their behavior on computers and online networks and how computers and networks in turn influence an individual’s psychology.

Already research into social networks have built algorithms that say a lot about the individual: “By looking at your Facebook profile or your Twitter feed, we can very accurately predict very intimate traits that you may not be aware you’re revealing,” said Stanford University’s Michal Kosinski to CBC Canada. By looking at facebook profiles and friend networks, his lab’s algorithm’s can predict sexual orientation, IQ, as well as political and religious identification[2].

My impression, based on a casual interest in the topic and reading pertinent articles when I come across them, is that a lot of cyberpsychology research that overlaps with psychiatry so far has focused on the prevalence of internet addiction and it’s relationship with depression, but it’s a new field, and we are only the tip of the iceberg, both in studying this topics and our interactions with machines. As our culture submerges into technologies like augmented and virtual reality, things are going to get increasingly complicated.

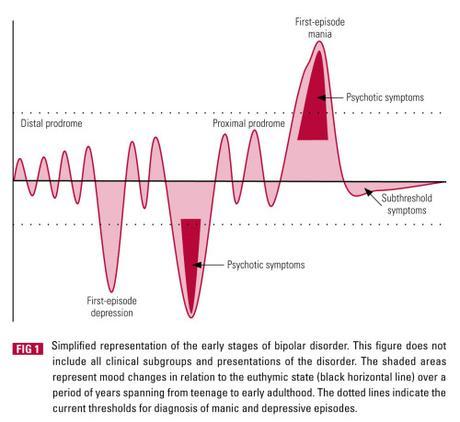

source: Ejalinthara et al., 2010

Detecting relapses

If we decide we don’t want to screen all users for mental illness, at the very least, we should be able to opt into service that can detect relapses. Illnesses such as bipolar disorder, depression, and the psychosis of schizophrenia have a periodic nature. Sufferers may have stretches of relatively normal mood and mindset and then abruptly descend back into mental illness. Sometimes this includes the onset of severe psychosis, with a loss of rationally thinking that can be both extremely dangerous and prevent the sufferer from having insight into his/her own condition.

A voluntary opt-in service could monitor patient’s social network activity and alert them, and/or their friends and family to abrupt changes in behavior. Perhaps with sophisticated algorithms we could even detect disorders in pro-dromal stages of the disease, when there are symptoms but it is not yet disruptive, such as the hypomania that can precede manic psychosis.

Final Conclusion

I’m sure other people have written about these topics before but it’s been relatively hard for me to find much about it in my searches, so if you know about these subjects please let me know because they really fascinate me.

For example:

- Do you know of any interesting stories related to this topic you could send my way?

- Have you or friends had personal experiences with mental illness that manifested in a strange way through the internet?

- Do you have your own ideas about how to screen for mental illness?

- Or do you believe strongly it’s unethical to screen?

Finally, I researched and wrote this for free out of the goodness of my heart (and an insatiable need for the approval of strangers), so if you liked this article please share it, or follow me to get notified about future articles. And if you didn’t like the article, write a comment if you please about why it was a piece of shit.

Footnotes (Tangents/Bad Jokes)

[1] And could alter how often positive or negative posts were seen to manipulate our emotions.

[2] If I recall correctly, one of these studies showed that a Facebook interest in curly fries was the most correlated interest with having a high IQ.