This is the fourth of Laura Wilson's 'Stratton' series of crime novels, which are set in the 1940s and 50s, and feature the appealing DI Ted Stratton. I've read them all now, though slightly out of order, and reviewed two of them -- Stratton's War and An Empty Death. I'm not sure why I didn't review A Capital Crime, though possibly it was partly because I liked it a little less than the first two. Not that there's anything wrong with it -- far from it, as I can't imagine that Laura Wilson would be capable of writing a bad novel. The problem I had with it was that it was based rather closely on a real and very famous case, or rather two cases, those of Timothy Evans and John Christie, both of whom lived at 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill, in the 1950s. Knowing quite a lot about the real events, I had trouble separating that knowledge from the fiction of the novel. But don't let that put you off, as you probably wouldn't react in the same way, and I see Amazon has lots of 5 star reviews for the novel.

This is the fourth of Laura Wilson's 'Stratton' series of crime novels, which are set in the 1940s and 50s, and feature the appealing DI Ted Stratton. I've read them all now, though slightly out of order, and reviewed two of them -- Stratton's War and An Empty Death. I'm not sure why I didn't review A Capital Crime, though possibly it was partly because I liked it a little less than the first two. Not that there's anything wrong with it -- far from it, as I can't imagine that Laura Wilson would be capable of writing a bad novel. The problem I had with it was that it was based rather closely on a real and very famous case, or rather two cases, those of Timothy Evans and John Christie, both of whom lived at 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill, in the 1950s. Knowing quite a lot about the real events, I had trouble separating that knowledge from the fiction of the novel. But don't let that put you off, as you probably wouldn't react in the same way, and I see Amazon has lots of 5 star reviews for the novel.

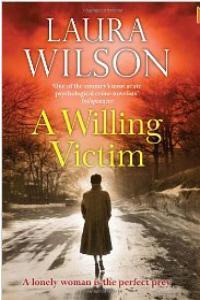

Anyway -- I found A Willing Victim absolutely superb. We've moved forward in time once more, and it's now 1956. As the novel begins, Stratton is starting an investigation of the murder of a young man, Jeremy Lloyd, who has been found dead in his London bedsit. Lloyd, it turns out, has been involved for many years with The Foundation for Spiritual Understanding, an organisation based in a gloomy, possibly haunted, Suffolk mansion and run by one Mr Roth, an enigmatic foreigner who keeps the 'students' on a very tight rein indeed. When Stratton visits the Foundation, he encounters Michael, a twelve-year-old boy who is believed by the Foundation's members to have special powers, and indeed to be something along the lines of Buddha or Christ, and rumoured to have been immaculately conceived. He does, however, have a mother, the stunningly attractive Mary, or Ananda (=bliss), as she has been renamed by Roth. However beautiful and charming she may be, though, Mary/Ananda proves to have a very dodgy past, and Stratton soon gets enmeshed in an investigation of various births, adoptions, and infant deaths, which proves really hard to unravel. The apparently unrelated death of another woman in the nearby woods only adds to the confusion. And if that were not enough, Stratton is also in a muddle about his relationship with beautiful upper-class Diana, and trying to come to terms with some very challenging news about his beloved daughter Monica. Times are changing -- will Stratton be able to keep up?

I recently read a Daily Mail article online in which Laura Wilson talked about her own upbringing by parents who were members of what the Mail (and presumably Laura herself) describes as a cult -- The School of Economic Science. Clearly the fictional Foundation is based very closely on this organisation, and pretty strange and repressive it sounds. Today, of course, people are generally much more familar with this sort of thing, with its roots in various Eastern philosophies and its promises of spiritual development. But it's all news to Stratton in 1956, and he takes a very sceptical view of the beliefs and activities of the Foundation and its members, though it does make him think and question, not a bad thing. Stratton is in fact a most marvelous fictional creation -- an honest man, brought up on a farm in Dorset, widowed in the war, intelligent and thoughtful but by no means intellectual, very traditional by nature but open, in the end, to questioning and even trying to accept new ideas and changing times.

There are, of course, other crime writers who set their novels in the mid-20th century -- the Lydmouth series by Andrew Taylor springs to mind as a very good example, and I've just finished Ruth Rendell's The Monster in the Box which, though set in the present, takes Inspector Wexford back into his own early days in the police force. But for my money, Laura Wilson does it best. It's all done so seamlessly, and the period evoked so perfectly, that you hardly realize you are reading a historical construct. Part of this, of course, includes the penalties suffered by her various perpetrators, which sometimes seem extremely harsh by today's standards, and in this novel particularly I longed for some kind of hint that perhaps some mercy and understanding might be shown to one invidual. But I'm afraid that would probably would not have been the case at the time, and I was left with rather an aching heart. I can't say more, though you'll know what I mean if you have read it. If you haven't, well, time you did. Excellent stuff.