By Kelly Raftery

It was the fall of 1994, a year and a half or so after the collapse of the Soviet Union. I had just signed on with a small company out of Washington, D.C., that had landed its first Russia contract. I was hired as the project’s country and language specialist, a hardened and tested post-Soviet veteran of two years at the ripe old age of 24. After two years of living in hyper-inflation, lawlessness and general societal chaos had not led me to be overly trusting of businesses or individuals, so I bypassed the lodging that was suggested to me and arranged for my own apartment until I could get my bearings.

After too many hours of flying, I remember being greeted at the door by a woman who seemed very old to my twenty-four year old eyes, but who I realize now was more likely in her late 50s or perhaps early 60s. Walking straight upright, her gray hair in a bun at the nape of her neck, she led me into her apartment, which was dark and close, but impeccably clean. The landlady showed me to the den, which would serve as my lodgings for the week. A fold-out sofa shared space with a wall of glass-fronted bookcases and a grand piano covered in intricate doilies. Large windows with orange velvet curtains let in great streams of light that highlighted the honey-colored parquet flooring.

Before this job, I recruited personnel for a multinational corporation just getting started in the former Soviet Union and the rule was do not interview anyone over forty years old, because they simply would not be able to make the mental and professional transition from a Soviet mindset to a western capitalist one. Anyone over forty was simply a lost cause, according to the corporate gurus. My landlady still worked at her government job, but her salary amounted to nothing in those days of hyperinflation, when salaries remained the same but the money was worth less and cost of everything else increased by leaps and bounds daily. On the day before I was to depart the apartment and take up my long-term lodgings, I made a shopping trip and stocked her refrigerator and stacked her counters high with non-perishable goods. I suppose it was guilt that drove me to do it, knowing that I had paid hundreds of dollars more than she had ultimately received for use of her room, knowing that I had turned down desperate job applicants as lost causes because they were deemed too old, hoping that maybe if I helped one woman in this small way, it would make some difference. I was idealistic.

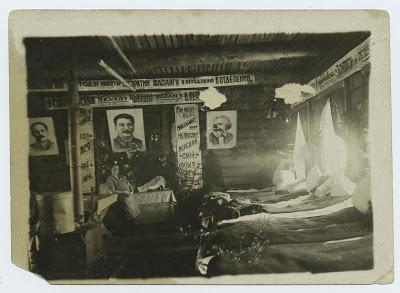

Stalin-Era Gulag,a likely destination for an Enemy of the People

When it came time to leave, I paced a bit waiting for the car and driver; my bags stacked in the narrow hallway, my landlady waiting for me lock the apartment door. I nonchalantly mentioned to her that my new lodgings came with a café that would serve us meals, so I was leaving all the food in the kitchen behind. Tears showed in the corners of her eyes. Urgently and in complete silence, she grabbed at my sleeve and pulled me into a small space between doors, outside of the apartment, but not quite fully into the hallway. She stooped down low and motioned to me to do the same, bringing our faces within an inch of each other. She drew my hair aside gently and whispered to me, “There is something I must tell you. I have never told another living soul. But you are different, a foreigner.” The silence stretched out as she gathered her courage and breathed into my ear, “My father. He was an Enemy of the People. They came and took him away when I was just a child. I never saw him again. I lived with this my whole life. Please don’t tell anyone.” She straightened, turned and went into her apartment, puttering around as if nothing had happened.An Enemy of the People. I knew from my graduate studies what had probably happened to her father--picked up, maybe tried, either executed or sent to Siberia along with millions of others who likely had committed no crime at all. Stalin was arbitrary and horrible like that. The Soviet Union had collapsed, the archives thrown open, and yet she still believed that the system that punished her father would come back to life and exact revenge on her. My landlady’s fear was real and palpable. I don’t know why she told me her secret that day, perhaps she had just carried the truth inside for too long, perhaps she thought her secret would be safe with me, or that I would not hold her father’s “crimes” against her.

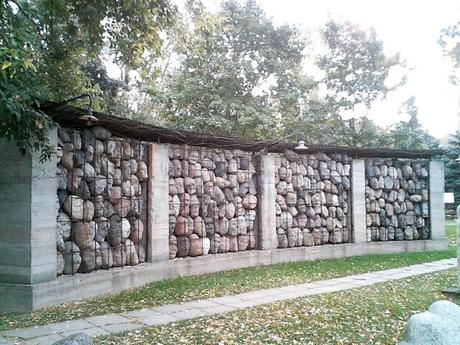

A memorial outside of Moscow to the millions killed during the Stalin-era repression.

The driver knocked at the door and took my bags down to the car. I said good-bye and thank you to my landlady. I never saw that woman again, but I never forgot her, either. For the first time in my life, history reached out and touched me viscerally with a tug on my shirtsleeve and a puff of air brushing past my ear. Twenty years later, I still remember that moment, though I have forgotten which city it was or even what job I had been sent to Russia to do. I still wonder about her story and all those years she lived with that secret.