I first encounted it in the context of an interview with Richard Marken on a now defunct blog (pdf of the archived page; link to page and scroll down to "Interview with Richard Marken"). Marken and I got into it a bit in the comments, as you will see! I was not impressed. However, Mansell & Marken (2015) have just published what they pitch as a clear exposition of what PCT actually is and how it works. I took the opportunity to read this and evaluate PCT as a 'grand theory of behaviour'.

My basic opinion has not changed. PCT is not wrong in most of it's basic claims, but it has no theory of information or how that information comes to be made or relate to the dynamics of the world. It's an unconstrained model fitting exercise, and it's central ideas simply don't serve as the kind of guide to discovery as a good theory should. Ecological psychology does a much more effective job of solving the relevant problems.

Mansell & Marken first talk about stimulus-response behaviourism and cognitive theories as the two basic 'grand theories of behaviour', and point out (correctly) that they both treat behavior as the output of a system. For example, when pressing a button, that press is the 'last step in a causal chain that starts in the nervous system and ends in the observed behaviour' (pg 426). Powers' insight was that the behavior depends on both the actor and the environment. In order to produce a stable behavior (e.g. a button press) the actor must constantly modulate the forces involved to cope with variations in the way the button responds. You get the same end from multiple means, and preserving an outcome in the face of variability and perturbation signals a process of control.

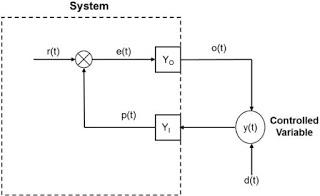

Figure 1. The basic sketch of Perceptual Control Theory

Figure 1 shows the idea. An organism is trying to control the perceived value p(t) of a variable y(t) so that it matches a target reference value r(t). You build your system so that it's activity works to control that perception and boom!, functional behavior with respect to the controlled variable.If the system is properly designed so that the error drives the output in a way that pushes the controlled variable, and thus the perception of the controlled variable, towards the goal specification, then the goal result will be produced.The paradigm test case for PCT has, funnily enough, been the outfielder problem. Marken has some papers (e.g. Marken, 2005) modelling interception in terms of moving so as to control the perceived (optical) velocity of the ball and keep it at a reference value of zero. He can get this to work in a variety of interception tasks (animated demos here). I'm not sure this account can replace the existing OAC and LOT strategies; for example, Marken's model produces linear optical trajectories while controlling velocity and the evidence I think suggests people are actually moving to control the trajectory and not the velocity.

pg 427

An evaluation

This is the basic limitation of PCT; it has no theory of what perceptual information is and what kind of information is created in given tasks. This really shows up in the other thing Marken has modeled, bimanual coordinated rhythmic movement. Here he produces a model that manages to produce some of the effects seen in Meschner et al (2001), a Nature paper on the perceptual basis of coordination that completely fails to engage with any of the literature on that topic and that makes inaccurate claims about what that perceptual basis is. Marken's model works to control things like the relative angle between the flags in the experiment, their speed, and then finally the velocity of the hands. He produces some of the effects, but then at the end notesThe model is not yet able to capture the fact that participants producing antiphase rotations would often end up controlling for symmetry as they increased the speed of flag rotation. Apparently, control of the perception of symmetry is preferred to control of the perception of antiphase. The model does not yet explain this preference.This is the switch from anti-phase to in-phase that is literally one of the signature features of coordinated rhythmic movements. His model can't account for it because he built it to control things that the actual system is not controlling (contrast this to the Bingham model). So he can fit some data, but not explain the behavior (proper mechanistic explanations need real parts and operations and without a theory of what information actually is his model cannot explain anything).

Further thoughts

While I don't think PCT is worth pursuing in and of itself, I do think this is a bit of a shame because I do think most of the basic analysis is right. We do organize our behavior so as to build a task specific device ('a properly designed system') that, when controlled by information present in tasks, works in such a way as to complement the demands of that task. I don't think this requires internal representation of goal states (r(t)) but the essence of PCT is a closed loop control system, which is very ecological. I'm also finding the language of exactly what control means to be very useful in a paper I'm working on with Sabrina.PCT is nowhere as influential as this article implies; based on their own references, there are just a handful of people doing PCT work and only two of them (the authors) are doing it properly. This makes some of their grand claims about the status and influence of PCT come across as just weird. My hunch is that PCT has not gone anywhere because it provides no guide to discovery. It is a sensible principle but with no theory or methods to shape how that principle is applied to specific behaviours. Right or wrong, the ecological approach provides this guide in spades and we have the empirical literature to prove it.

Summary

Perceptual Control Theory is interesting and it's basic insight (that behavior is the result of closed loop control) is essentially correct. However, PCT is not the only theory to realize this. The ecological approach has this idea at it's core as well and has the added benefit of being able to guide discovery and empirical research.References

Mansell, W. & Marken, R. S. (2015). The origins and future of control theory in psychology. Review of General Psychology, 19(4), 425-430. Download ($$)