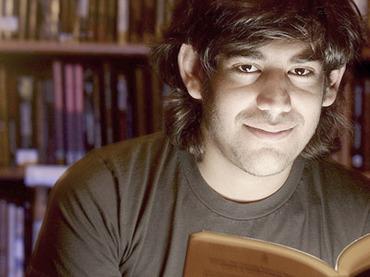

Aaron Swartz

We mark the birthday of civil-rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. today, along with the re-inauguration of President Barack Obama. Sadly, the recent suicide of cyberactivist Aaron Swartz hangs over both events, a grim reminder that the justice for which King fought has been allowed to veer badly off track by our nation's first black president.

To be sure, Obama inherited a dysfunctional justice department from George W. Bush, one marked by historic abuses of prosecutorial powers. But Obama has done precious little to clean up the mess, and now the Aaron Swartz tragedy rests at his doorstep.

The death of Swartz, at age 26, makes you sad upon first reading about it. As you begin to learn more about the circumstances behind his suicide, you become angry. As you realize how much he had to offer, and how easily his death could have been avoided, you begin to seethe. I'm past seething to the point of wanting to see Massachusetts U.S. Attorney Carmen Ortiz and her assistant thugs run over by a bus.

Why the visceral reaction on my part? Perhaps it's because, as a resident of Alabama, I became intimately familiar with bogus federal charges against our former Democratic governor, Don Siegelman, during the Bush years. That case has become known as perhaps the most notorious political prosecution in American history. The Swartz case was tinged with politics of a different sort; it seems to have had little to do with Swartz's politics, but Ortiz apparently saw the case as one that might advance her cause for higher office.

Instead, it might make her go down as one of the most loathed Democrats ever. An online petition calls for her ouster, and the U.S. House Oversight Committee has launched an investigation of her. In many ways, Ortiz seems like a cross between Leura Canary and Alice Martin, the Bush-era duo who went after Siegelman here in Alabama.

In fact, the Swartz cases raises all sorts of ugly reminders about the Siegelman case. Let's take a look at a few of them:

* Both Swartz and Siegelman faced financial ruination--We don't know for sure how much Siegelman was forced to spend on his legal defense, but it almost certainly ranged well into the seven figures. Sources tell Legal Schnauzer that the former governor's second defense lawyer, Haskell Slaughter's G. Douglas Jones, charged him $300,000--and Jones did not even take the case to trial.

Swartz also was looking at being financially destroyed. A Boston Globe article quotes John Summers, a friend of Swartz and the editor of The Baffler magazine:

Swartz never profited from the material he downloaded, was “financially ruined’’ by the federal case, and still needed $100,000 for his defense, said Summers.

“He was looking at entering federal prison and being branded a felon, which would change his life for doing something that is at best the equivalent of trespassing,” he said.

* Neither Swartz nor Siegelman sought to benefit financially--It long has been established that Don Siegelman did not benefit financially from the transaction that landed him in federal prison. The contribution went to a campaign to establish an education lottery in Alabama.

Even Carmen Ortiz, in a statement after Swartz's death, acknowledged that he did not seek to experience financial gain:

On Wednesday night, the U.S. Attorney's office in Massachusetts broke its silence over the Swartz case. A statement from U.S. Atty. Carmen M. Ortiz extended "heartfelt sympathy" to Swartz's family and supporters but held firm on the office's stance that Swartz should serve at least six months in prison. Her prosecutors handling the case, she said, had acted "reasonably."

"The prosecutors recognized that there was no evidence against Mr. Swartz indicating that he committed his acts for personal financial gain, and they recognized that his conduct -- while a violation of the law -- did not warrant the severe punishments authorized by Congress and called for by the sentencing guidelines in appropriate cases," Ortiz said in the statement.

* Both Swartz and Siegelman were targeted for actions that many legal experts do not consider crimes--In the Siegelman case, he was charged with federal-funds bribery under a statute that is virtually indecipherable. In the context of a campaign contribution, as in the Siegelman case, one has to look to case law to have any grasp of the fine line between an illegal "quid pro quo" and standard political activity. More than 100 former state attorneys general have stated that the alleged actions in the Siegelman case did not constitute a crime.

Don Siegelman

Similar confusion exists in the Swartz case, where he was alleged to have entered a closet at MIT to download academic articles that were offered for a charge at the online site JSTOR. Swartz felt the articles, which had been written based on publicly funded research, should be free to the public. As John Summers noted above, this might have been, at most, an act of criminal trespass--and that is a state violation and not even a misdemeanor in many jurisdictions. So why was this treated as a federal crime?Writing at The Atlantic, Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig said any wrongdoing on Swartz's part amounted to violation of a terms of service agreement:

Aaron's alleged "crime" was that he used MIT's network to access a database of academic journal articles (JSTOR) and download millions of those articles to his laptop computer. He didn't "hack" the network to secure those downloads: MIT is a famously open network. He didn't crack any special password system to get behind JSTOR's digital walls. He simply figured out how JSTOR was filing the articles that he wanted, and wrote a simple script to quickly gather those articles and then copy them to his machine.

Perhaps Swartz violated his contract with JSTOR, Lessig writes, but that normally does not lead to felony charges under American law:

The "terms of service" (TOS) of any website are basically a contract. They constitute an agreement about what you can and can't do, and what the provider can and can't do. Not everything on a website is governed by contract alone: Copyright and privacy law can impose property-like obligations independent of a TOS. But the rules Aaron were said to have violated purported to limit the amount of JSTOR that any user was permitted to download. They were rules of contract. Aaron exceeded those limits, the government charged. He therefore breached the implied contract he had with JSTOR. And therefore, the government insists, he was a felon.

It's that last step that is so odd within the tradition of American law. Contracts are important. Their breach must be remedied. But American law does not typically make the breach of a contract a felony. Instead, contract law typically requires the complaining party to prove that it was actually harmed. No harm, no foul. And in this case, JSTOR -- the only plausible entity "harmed" by Aaron's acts -- pled "no foul." JSTOR did not want Swartz prosecuted. It settled any possible civil claims against Swartz with the simple promise that he return what he had downloaded. Swartz did. JSTOR went away.

The Obama Justice Department, however, would not go away. It insisted that Swartz be punished with prison time, a guilty plea to a felony, and a bankrupting fine--or he would have to prove his innocence in a bankrupting trial. Writes Lessig:

We have built a system of criminal law that depends upon our trusting the government. Few civil libertarians from either the right or the left, though, will be surprised that it turns out that the bureaucrats manning the battle stations cannot be trusted.

It seems clear that we cannot trust individual prosecutors to exercise their discretion in a reasonable fashion. It also seems clear that we cannot trust Main Justice to exercise oversight over the rogues in its ranks. Tim Wu, of The New Yorker, makes that point in a piece titled "How the Legal System failed Aaron-Swartz--and Us."

Yes, most of the time prosecutors do chase actual wrongdoers, but today our criminal laws are so expansive that most people of any vigor and spirit can be found to violate them in some way. Basically, under American law, anyone interesting is a felon. The prosecutors, not the law, decide who deserves punishment.